| Transition Temperature | 260 K |

|---|---|

| Experiment Temperature | 150 K |

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | R-3 (#148) |

| Magnetic Space Group | P-1 (#2.4) |

| Magnetic Point Group | -1 (2.1.3) |

| Lattice Parameters | 5.23210 5.23210 14.37220 90.00 90.00 120.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1002/anie.201609762 |

| Reference | A.J. Dosâ santos-Garcia, E. Solana-Madruga, C. Ritter, A. Andrada-Chacon, J. Sanchez-Benitez, F.J. Mompean, M. Garcia-Hernandez, R. Saez-Puche and R. Schmidt, Angewandte Chemie International Edition (2017) 56 4438-4442. |

Magnetic Properties

Large Magnetoelectric Coupling Near Room Temperature in Synthetic Melanostibite \( Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6} \)

Antonio J. Dos santos-García, \( ^{*} \) Elena Solana-Madruga, Clemens Ritter,

Adrián Andrada-Chacón, Javier Sánchez-Benítez, Federico J. Mompean,

Mar Garcia-Hernandez, Regino Sáez-Puche, and Rainer Schmidt

Abstract: Multiferroic materials exhibit two or more ferroic orders and have potential applications as multifunctional materials in the electronics industry. A coupling of ferroelectricity and ferromagnetism is hereby particularly promising. We show that the synthetic melanostibite mineral \( Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6} \) ( \( R\bar{3} \) space group) with ilmenite-type structure exhibits cation off-centering that results in alternating modulated displacements, thus allowing antiferroelectricity to occur. Massive magnetoelectric coupling (MEC) and magnetocapacitance effect of up to 4000% was detected at a record high temperature of 260 K. The multiferroic behavior is based on the imbalance of cationic displacements caused by a magnetostrictive mechanism, which sets up an unprecedented example to pave the way for the development of highly effective MEC devices operational at or near room temperature.

There has recently been a strong rise of research interest in multiferroic materials that can combine several ferroic orders in one single phase or in heterostructures consisting of different single ferroic layers. \( ^{[1-5]} \) Particularly interesting are 1) the magnetoelectric coupling (MEC) of ferroelectricity and ferromagnetism for magnetically accessible ferroelectric

[‡] Dr. A. J. Dos santos-García

Dpto. Ingeniería mecánica, química y diseño industrial, ETSIDI. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, 28012 Madrid (Spain) E-mail: aj.dossantos@upm.es E. Solana-Madruga, Prof. Dr. R. Sáez-Puche Dpto. Química Inorganica I, Fac. Químicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28040 Madrid (Spain)

Dr. C. Ritter

Institut Laue-Langevin, 38042 Grenoble Cedex (France) A. Andrada-Chacón, Dr. J. Sánchez-Benítez

Dpto. Química Física I, MALTA Consolider Team, Fac. Químicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28040 Madrid ( Spain) Dr. F. J. Mompean, Prof. Dr. M. Garcia-Hernandez

Instituto de Ciencias de Materiales, CSIC 28049 Madrid (Spain)

and Unidad Asociada “Laboratorio de heteroestructuras con aplicación en espintrónica”, UCM/CSIC, 28049 Madrid (Spain)

Dr. R. Schmidt

Dpto. de Física de Materiales, Fac. Físicas, GFMC, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28040 Madrid (Spain)

and

Unidad Asociada “Laboratorio de heteroestructuras con aplicación en espintronica”, UCM/CSIC, 28049 Madrid (Spain)

Supporting information and the ORCID identification number(s) for the author(s) of this article can be found under: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201609762. (FE) random access memories (FE-RAM) for use in information technology, and 2) magnetocapacitance (MC) effects for tunable capacitors in the communication technology sector. The former mechanism requires a strong coupling of ferroelectric and magnetic orders, that is, it is imperative that the magnetization (polarization) can be modified by applying an electric (magnetic) field and vice versa, which may lead to the design of FE-RAMs with physically separated read and write mechanisms. \( ^{[6]} \) MC effects present at low fields are much sought after for allowing simplified resonance tuning in LC circuits. Multiferroic applications in spintronics have been proposed for example in magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs) where a multiferroic barrier can increase the number of logical states. \( ^{[7,8]} \)

Multiferroic materials can be widely classified into two types: \( ^{[9]} \) in type-I multiferroics, ferroelectricity, and magnetism rely on two independent mechanisms, whereas in type-II the ferroelectricity directly arises from the magnetic order, thus only existing in a magnetically ordered state. The intrinsic relation of the ferroelectric order to the magnetic one in the latter is expected to produce large MEC effects, but such ferroic properties tend to appear at rather low temperatures. This coupling often involves spiral spin structures. \( ^{[10-14]} \) In contrast, type-I multiferroics tend to show much higher ferroic transition temperatures at the expense of a small MEC. \( ^{[15]} \)

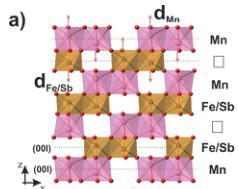

ABO_{3} oxides and their ordered quaternary derivatives AA'B_{2}O_{6} or A_{2}BB'O_{6} with Mn^{2+} on the A site are of fundamental interest and require the use of high pressure to be stabilized. \( ^{[16-21]} \) Herein we report the exceptional case of a massive MEC effect at the elevated temperature of 260 K on polycrystals of the high pressure ilmenite Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6} (I_{2}Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6}). Rietveld refinement of the powder neutron diffraction (PND) pattern collected at room temperature (Supporting Information, Figure S1) confirms the crystallization of I_{2}Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6} in the R3 space group. Structural refinement results are summarized in the Supporting Information, Table S1. Figure 1a shows the [110] projection of a portion of the ilmenite structure with a stacking sequence along [001] Mn-Sb/Fe-□-Sb/Fe-Mn-□ (□=vacant site). Owing to the cation-cation repulsions, commonly observed in corundum and its derivatives, \( ^{[22]} \) cations are off-centered from (00l) planes within the octahedra in a cooperative manner resulting in alternating modulated displacements. This gives rise to a macroscopically centrosymmetric space group, but the localized type of cationic displacement (d_{Mn}=0.403 Å and d_{Fe/Sb}=0.216 Å) may still permit antiferroelectricity to occur. \( ^{[23]} \)

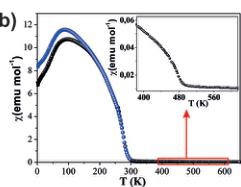

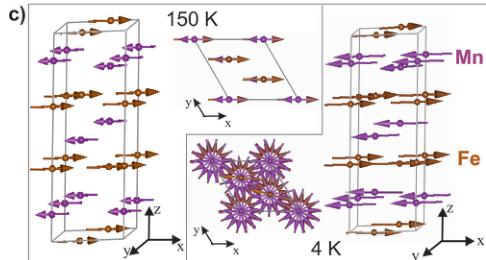

Figure 1. a) [110] Projection of a portion of the nuclear \( L_{Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6}} \) structure illustrating the cation ordering and cation displacements \( (d_{\mathrm{M}}) \) above and below (00l) planes. b) Temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility. The inset shows an enlargement of the 380–550 K temperature range. c) Different projections of the magnetic structures determined by PND at 150 K (left polyhedron) and 4 K (right polyhedron). The top views of the structures perpendicular to the xy plane give evidence of the spin rotation below \( T_{N2} \) .

Figure 1b shows the temperature \( (T) \) dependence of the magnetic susceptibility for \( L_{Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6}} \) from 650 to 2 K measured under a magnetic field \( (H) \) of 0.1 T. A nearly imperceptible change (see inset of Figure 1b) in the Curie constant appears at approximately 500 K. The presence of parasitic \( \mathrm{MnFe_{2}O_{4}} \) ( \( T_{C}=470~K \) ) is discarded as our PND data collected at room temperature do not show either its nuclear or its magnetic peaks. The susceptibility follows a Curie–Weiss behavior over the temperature range 650–530 K. The fitted Weiss constant \( (\theta) \) amounts to -464.4 K and the magnetic moment to \( 9.54\mu_{B}/f.u \) , which is close to the theoretical value \( (10.25\mu_{B}/f.u.) \) expected for the contribution of \( 2Mn^{2+} \) and \( Fe^{3+} \) ions. Upon cooling below 300 K the susceptibility increases sharply and a ferrimagnetic transition at \( T_{N1}\approx260~K \) is attributed to the antiparallel alignment of the two sublattices of \( Mn^{2+} \) and \( Fe^{3+} \) spins. \( ^{[24]} \) This scenario is supported by field dependent magnetization measurements depicted in the Supporting Information, Figure S2. The ZFC curve diverges from the FC data below about 160 K followed by a broad maximum centered at 100 K (Figure 1b).

To determine the spin ordering, low-temperature PND experiments have been carried out. The thermal evolution of high intensity neutron diffraction data recorded between 4 K and 280 K shows an increase of some nuclear reflections below \( T_{N1} \approx 260 \) K (Supporting Information, Figure S3). The absence of new Bragg peaks appearing from this magnetic transition reveals a propagation vector \( \kappa_{1} = [0\ 0\ 0] \) . The magnetic structure, depicted in Figure 1c (left), was determined from the Rietveld refinement of the high-resolution 150 K PND data (Supporting Information, Figure S4a). Mn and Fe ferromagnetic sublattices couple antiparallel in a collinear ferrimagnetic arrangement. However, this structure does not represent the magnetic ground state of the system, as the appearance of new satellites around the (003) reflection below \( T_{N2} \approx 50 \) K (Supporting Information, Figure S3) indicates a second magnetic transition stabilizing an incommensurate magnetic structure. It has been determined from the Rietveld refinement of the high-resolution PND data collected at 4 K (Supporting Information, Figure S4b), and it can be described as a helix running along the c-direction, defined by \( \kappa_{2} = [0\ 0\ 0.07] \) , with the magnetic moments turning within the basal ab-plane (Figure 1c-right and Supporting Information). Thus, \( L_{Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6}} \) undergoes a symmetry-breaking phase transition between commensurate and incommensurate magnetic structures. As a consequence of this transition the time-reversal and the inversion symmetry could break allowing the presence of electric polarization coupled to the direction of spin rotation. \( ^{[25,26]} \)

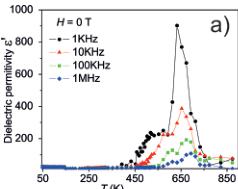

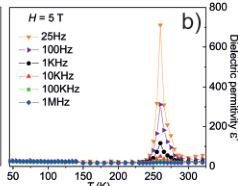

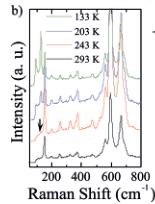

Therefore, the frequency \( (f) \) and T dependent dielectric properties of \( L_{Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6}} \) bulk material have been investigated through impedance spectroscopy. \( ^{[27,28]} \) Figure 2a shows dielectric spectroscopy data collected at 45–900 K in the format of dielectric permittivity \( (\varepsilon^{\prime}) \) with H=0 T. The \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) vs. T curves at various frequencies indicate a large peak at about 650 K, which reduces in height by increasing f. This is the typical behavior of a relaxor ferro- or antiferroelectric

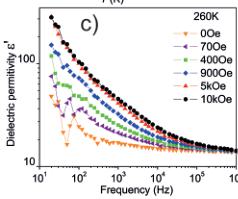

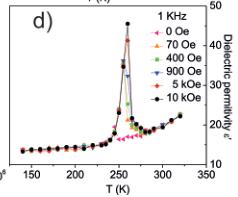

Figure 2. a) \(\varepsilon^{\prime}\) vs. \(T\) at various frequencies under \(H=0\) T for the 10–900 K temperature range. b) \(\varepsilon^{\prime}\) vs. \(T\) at various frequencies under \(H=5\) T. c) \(\varepsilon^{\prime}\) vs. \(f\) under different \(H\) at 260 K. d) \(\varepsilon^{\prime}\) vs. \(T\) under different \(H\) at \(f=1\) kHz.

material. This maximum displays a shoulder on its left side centered at about 500 K, which can be resolved as a second dielectric peak through high resolution measurements (Supporting Information, Figure S5), and which is coincident with the subtle change occurring at about 500 K in the magnetic susceptibility measurements. Owing to the non-polar structural symmetry and the alternating cationic displacements in the \( L_{Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6}} \) it is reasonable to assume an AFE

structure. The definition of an antiferroelectric material has been the subject of long discussions in the literature. We find it useful to adopt here the definition proposed by Rabe, \( ^{[23,29]} \) where antiferroelectrics are clearly distinguished from the much larger class of materials with centrosymmetric structures (antipolar materials) described by oppositely directed dipoles created by ionic displacements but without a transition into a ferroelectric phase. We have performed P vs. E measurements at room temperature but any AFE double hysteresis loops have been observed, which is possibly due to our experimental limits of 20 kV. However, the appearance of this AFE order as a shoulder of an immediate massive peak in the dielectric permittivity points to the existence of a thermally activated transition from the AFE to a FE state. The observation that the transition into a low-temperature AFE phase occurs in two steps is not unusual and has previously been observed in blue bronze materials. \( ^{[30]} \)

It is noteworthy that the imeline structure allows different forms of magnetic control of the electric polarization: linear and non-linear MEC \( ^{[31-33]} \) . These effects occur in AFM and FM/ferrimagnetic materials. \( ^{[33]} \) Consequently, we have measured the \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) vs. T curves for various f from 45–320 K under 5 T (Figure 2b). Surprisingly, these data do not show any coupling between the polarization and the helical magnetic structure below \( T_{N2} \approx 50 \) K but a massive MEC at the ferrimagnetic transition temperature \( T_{N1} \approx 260 \) K. The Shubnikov magnetic point group at the ferrimagnetic transition is -3, which allows a non-linear magnoelectric effect corresponding to the \( H_{i}E_{i}E_{k} \) type (simplified as HEE): this effect describes the dependence of the dielectric permittivity on a magnetic field \( ^{[33]} \) where \( H_{i} \) is the magnetic field, \( E_{j} \) is the electric field, and \( E_{k} \) represents the spontaneous dielectric polarization. The occurrence of such a coupling is evidenced by the appearance of the large peak in Figure 2b with an increase in \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) by a factor of up to about 40 (4000%). The increase of \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) from the low temperature value of about 15 to about 700 (f = 25 Hz) at 260 K corresponds to an increase of the polarization of about 7.4 nC m \( ^{-2} \) to about 34.7 \( \mu \) C m \( ^{-2} \) at the small applied electric field of 56 V m \( ^{-1} \) in our measurements. Artificial MEC related to secondary relaxations and magnetoresistance can be ruled out since all \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) vs. f curves measured under different H at 260 K (Figure 2c) show only signs of one dielectric contribution, otherwise a secondary relaxation would appear as a second permittivity plateau at low \( f^{[34,35]} \) Figure 2d illustrates that the MEC occurs if \( H \geq 70 \) Oe is applied. The value of 70 Oe is above the small coercive field (ca. 30 Oe) detected for the ferrimagnetic order (Supporting Information, inset of Figure S2). It is expected that the magnetic field needed for inducing magnetocapacitance in \( I_{Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6}} \) , as low as 70 Oe, may help to overcome the technological barriers for future applications.

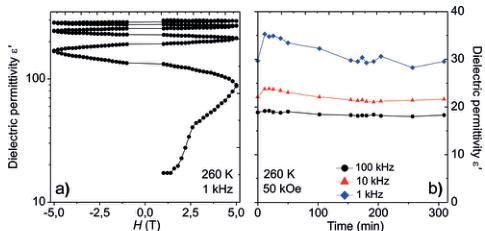

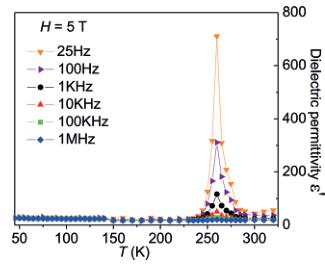

To further classify the origin of the massive MEC effect at 260 K we have studied the effect of the exposition to oscillating magnetic fields on \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) vs. T plot (Figure 3a). Cycling H at a fixed \( T_{N1} \approx 260 \) K between \( \pm 5 \) T a continuous increase of \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) takes place. This result is surprising since the high \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) and the coupling do not seem to disappear as H is reduced below 30 Oe during the cycling process. The high \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) only disappears upon heating to T > 300 K. This behavior points to a rather

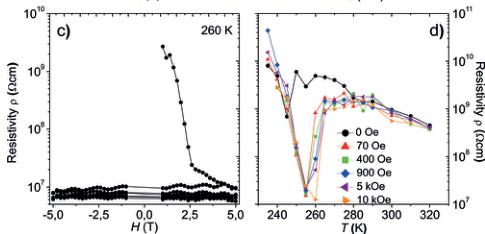

Figure 3. a) \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) dependence on an oscillating H of \( \pm5 \) T at 260 K and f=1 kHz. b) Temporal stability of the \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) values reached under H=5 T at 260 K and different f. c) \( \rho \) dependence on the oscillating H at 260 K. d) Temperature dependence of \( \rho \) under different H.

slow dynamics of the MEC mechanism, which could be related to metastable local distortions induced by magnetostriction. After several H cycles the large \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) value progressively tends towards a certain top limit.

The complementary time dependent \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) measurements at constant H (5T) and T (260 K) did not result in any significant increase of \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) (Figure 3b) and we therefore conclude that the local distortions are time independent but stabilized and enhanced by a changing H. The magnetoresistance behavior of the sample was studied by the variation of the resistivity ( \( \rho \) ) 1) under the same H cycling procedure at \( T_{N1} \) (Figure 3c) and 2) by applying different magnetic fields in the 230–320 K temperature range (Figure 3d). The \( \rho \) , obtained from complex impedance plots \( -Z^{\prime\prime} \) vs. \( Z^{\prime} \) (Supporting Information, Figure S6), \( ^{[36]} \) drops very quickly over several orders of magnitude during the first magnetic cycle (Figure 3c), which constitutes a colossal magnetoresistance (CMR) effect. The application of any constant H higher than 30 Oe already induces the rapid drop in \( \rho \) (Figure 3d), but \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) increases more continuously. This observation and the fact that \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) vs. f (Figure 2c) shows the signs of only one dielectric contribution, implies that the observed CMR effect cannot be responsible for the giant MEC. \( ^{[34]} \) The significant changes of \( \rho \) and \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) at \( T_{N1} \) must be a reflection of the changes in the crystal structure induced by H, where \( \rho \) describes changes in the charge carrier mobility and \( \varepsilon^{\prime} \) in the lattice polarizability. In the absence of H, the local cation environments may be regarded as rather rigid: not susceptible to electric fields in terms of the polarizability. By the application of H at \( T_{N1} \) the local symmetry seems to get softened and becomes more

susceptible to electric fields, that is, polarizable, leading to a strong increase of \( \varepsilon' \) .

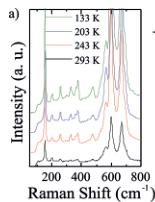

This lattice softening was confirmed by Raman spectroscopy measurements under an applied H. Factor group analysis yields 10 Raman active phonon modes \( \left(\Gamma=5A_{g}+5E_{g}\right) \) which are in good agreement with the Raman spectra of other R3 ilmenites. \( ^{[37,38]} \) The analysis and identification of the Raman modes as well as the Raman spectrum at room temperature are summarized in the Supporting Information, Table S2 and Figure S7 respectively. Figure 4a left shows selected Raman spectra at various temperatures for H=0 T. The evolution of the frequency for the different modes as a function of T is shown in Figure 4a (right). Each band shifts

Figure 4. Raman spectra of \( LMn_{2}FeSbO_{6} \) upon cooling from room temperature down to 100 K in the absence of H (a), and under an applied H=0.4 T (b). The right part of the figure shows the evolution of the Raman frequency shifts as a function of T for different selected modes.

to higher frequencies upon decreasing T, which is consistent with the typical behavior owing to the anharmonicity. The ten identified phonons were also observed at ambient temperature under a permanent H=0.4 T (Figure 4b (left)). However, at \( T<260~K \) , a new peak centered at \( 128~cm^{-1} \) (marked with an arrow in Figure 4b (left)), emerges. Its intensity quickly enhances with decreasing T and a second new peak appears concomitantly at \( 94~cm^{-1} \) . The possible appearance of electromagnon peaks was considered and discarded since the new phonons are visible at frequencies much higher than those commonly observed in electromagnons (typically \( <50~cm^{-1} \) ). Moreover, the applied magnetic field for our Raman measurements were about 0.4 T, enough for the symmetry breaking of this system but much lower than that normally needed for the emergence of electromagnon peaks (several Tesla typically). Therefore, these new peaks must arise from the local symmetry breaking when H is applied below the ferrimagnetic transition. The pseudosymmetric character of this transition is not always easy to establish experimentally; however, the evolution of some selected Raman frequency shifts as a function of T, Figure 4b (right), does not follow a linear trend as H is applied. The presence of an up-down feature around 260 K confirms the lattice softening at the \( T_{N1} \) ferrimagnetic transition. High-symmetry \( (R3) \) and pseudosymmetric structures should be nearly alike and distortions, probably related to the atomic displacements, may be such that they only occur at nanometric scale. Therefore, we demonstrate that both the time-reversal and spatial symmetry should be broken, thereby allowing the presence of non-linear HEE MEC.

Among the possible mechanisms originating multiferroicity from spin ordering, \( ^{[39]} \) the most plausible one for this compound seems to be magnetostriction. This microscopic mechanism has previously been observed in manganites, orthoferrites, other antiferromagnetic materials \( ^{[40-45]} \) and very recently in other ilmenites. \( ^{[46]} \) Figure 5 (left) shows the unit cell of \( I_{Mn,FeSbO_{6}} \) at room temperature (above \( T_{N1} \) ) and \( H=0~T \) . \( Mn^{2+} \) and \( Fe^{3+}/Sb^{5+} \) cations are symmetrically displaced by averaged distances of \( d_{Mn} \) ( \( 0.403\mathring{A} \) ) and \( d_{Fe/Sb} \) .

Figure 5. Representation of the structural distortions at room temperature under \(H=0\) T (left) and below \(T_{N1}\approx260\) K and \(H>0\) T (right).

(0.216 Å) from the center of the octahedra. The symmetric character of alternating displacements prevents a net electric polarization. Below \( T_{N1} \) , Mn spins order ferromagnetically within (00l) planes but antiferromagnetically to Fe spins along the c-axis (Figure 1b). This magnetic ordering breaks the time reversal symmetry but spatial inversion still produces no change in \( \varepsilon' \) , as demonstrated in Figure 2a. However, when H is applied at \( T_{N1} \approx 260 \) K, a non-linear HEE-type magnetoelectric effect is allowed. The neighboring \( Mn^{2+} \) and \( Fe^{3+} \) cations develop an additional displacement ( \( \delta \) ) with respect to that experienced under H = 0 T. Consequently, two different crystallographic positions arise for \( Mn^{2+} \) cations: those facing the diamagnetic \( Sb^{5+} \) , which do not suffer any \( \delta \) , and those facing \( Fe^{3+} \) , for which \( d_{Mn} = d_{Mn} + \delta \) . This situation is represented in Figure 5 right showing Mn-Sb and Mn-Fe pairs under an applied H. The local polarization arises from the \( Mn^{2+} \) displacement imbalance. Intriguingly, the disorder among Fe and Sb within the (0 0 0.3486) position is responsible for both the crystal centrosymmetry and its spatial inversion breaking when H is applied at \( T < T_{N1} \) . Therefore, the application of H below 260 K induces the breaking of

spatial symmetry in addition to the time reversal symmetry pushing the system to become multiferroic.

We have shown that a transition into a relaxor antiferroelectric phase occurs in two steps at about 500–650 K and that massive MEC and MC effects occur at the ferrimagnetic transition \( T_{Ni} \approx 260 \) K in \( L_{Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6}} \) . The compound may be useful in polycrystalline form for use in tunable capacitors, whereas potential application as a FE-RAM material or MTJ barrier would require the stabilization of \( L_{Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6}} \) by epitaxial strain in thin film devices.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank MINECO for funding through projects MAT2013-44964-R, MAT2013-41099-R, MAT2015-71070-REDC, MAT2014-52405-C02-02, CTQ2015-67755-C2-1-R (MINECO/FEDER) and FPI (BES-2013-066112) and Ramon y Cajal (RyC-2010-06276) fellowships, and Comunidad de Madrid through S-2013/MIT-2753 grant. RS acknowledges the help from Norbert Nemes and Neven Biskup with developing software. Thanks to Dr. Muñoz-Gil for high temperature dielectric spectroscopy measurements and thanks to M. Alguero and R. Jimenez for ferroelectric hysteresis measurements. Authors are also indebted to Institut Laue-Langevin for beamtime allocation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Keywords: high-pressure chemistry · ilmenite · magnetic properties · magnetoelectric coupling · non-linear MEC

[1] V. E. Wood, A. E. Austin, Int. J. Magn. 1974, 5, 303–315.

[2] N. A. Hill, J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 6694–6709.

[3] W. Eerenstein, N. D. Mathur, J. F. Scott, Nature 2006, 442, 759–765.

[4] H. Zheng, et al., Science 2004, 303, 661–663.

[5] Y.-H. Chu, Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 478–482.

[6] D. I. Khomskii, Bull. Am. Phys. Soc. C 2001, 21, 002.

[7] S. W. Cheong, M. Mostovoy, Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 13–20.

[8] M. Gajek, M. Bibes, S. Fusil, K. Bouzehouane, J. Fontcuberta, A. Barthélémy, A. Fert, Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 296–302.

[9] D. I. Khomskii, Physics 2009, 2, 20.

[10] T. Kimura, G. Lawes, T. Goto, Y. Tokura, A. P. Ramirez, Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 224425.

[11] B. B. Van Aken, T. T. M. Palstra, A. Filippetti, N. A. Spaldin, Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 164–170.

[12] Y. Yamasaki, S. Miyasaka, Y. Kaneko, J.-P. He, T. Arima, Y. Tokura, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 207204.

[13] Y. J. Choi, J. Okamoto, D. J. Huang, K. S. Chao, H. J. Lin, C. T. Chen, M. van Veenendaal, T. A. Kaplan, S.-W. Cheong, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 067601.

[14] Y. Tokura, S. Seki, Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 1554–1565.

[15] J. Wang, et al., Science 2003, 299, 1719–1722.

[16] A. J. Dos santos-García, C. Ritter, E. Solana-Madruga, R. Sáez-Puche, J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2013, 25, 206004.

[17] E. Solana-Madruga, A. J. Dos santos-García, A. M. Arévalo-López, D. Ávila-Brande, C. Ritter, J. P. Attfield, R. Sáez-Puche, Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 20441.

[18] A. M. Arévalo-López, G. M. McNally, J. P. Attfield, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12074–12077; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 12242–12245.

[19] M.-R. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12069–12073; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 12237–12241.

[20] E. Solana-Madruga, A. M. Arévalo-López, A. J. Dos santos-García, E. Urones-Garrrote, D. Ávila-Brande, R. Sáez-Puche, J. P. Attfield, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9340–9344; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 9486–9490.

[21] G. V. Bazuev, B. G. Golovkin, N. V. Lukin, N. I. Kadyrova, Y. G. Zainulin, J. Solid State Chem. 1996, 124, 333–337.

[22] R. P. Liferovich, R. H. Mitchell, Phys. Chem. Miner. 2005, 32, 442–449.

[23] K. M. Rabe in Functional Metal Oxides: New Science and Novel Applications, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2013, Chap. 7.

[24] R. Mathieu, S. A. Ivanov, G. V. Bazuev, M. Hudl, P. Lazor, I. V. Solovyev, P. Nordblad, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 202505.

[25] P. G. Radaelli, L. C. Chapon, Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 054428.

[26] T. Kimura, T. Goto, H. Shintani, K. Ishizaka, T. Arima, Y. Tokura, Nature 2003, 426, 55–58.

[27] E. Barsukov, J. R. Macdonald in Impedance Spectroscopy: Theory, Experiment and Applications, Wiley, Hoboken, 2005.

[28] R. Schmidt, W. Eerenstein, T. Winiecki, F. D. Morrison, P. A. Midgley, Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 245111.

[29] M. Retuerto, et al., Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 4320–4329.

[30] J. Gardner, F. D. Morrison, Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 11687–11695.

[31] N. Mufti, G. R. Blake, M. Mostovoy, S. Riyadi, A. A. Nugroho, T. T. M. Palstra, Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 104416.

[32] H. J. Silverstein, E. Skoropata, P. M. Sarte, C. Mauws, A. A. Aczel, E. S. Choi, J. van Lierop, C. R. Wiebe, H. Zhou, Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 054416.

[33] A. S. Borovik-Romanov, H. Grimmer in Magnetic properties, International Tables for Crystallography, Vol. D., Kluwer, Boston, 2003.

[34] G. Catalan, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 102902.

[35] R. Schmidt, J. Ventura, E. Langenberg, N. M. Nemes, C. Munuera, M. Varela, M. Garcia-Hernandez, C. Leon, J. Santamaria, Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 035113.

[36] J. T. S. Irvine, D. C. Sinclair, A. R. West, Adv. Mater. 1990, 2, 132–138.

[37] A. Dias, R. L. Moreira, J. Raman Spectrosc. 2010, 41, 698–701.

[38] T. Okada, T. Narita, T. Nagai, T. Yamanaka, Am. Mineral. 2008, 93, 39–47.

[39] Y. Tokura, S. Seki, N. Nagaosa, Rep. Prog. Phys. 2014, 77, 076501.

[40] N. Hur, S. Park, P. A. Sharma, J. S. Ahn, S. Guha, S.-W. Cheong, Nature 2004, 429, 392–395.

[41] Y. J. Choi, H. T. Yi, S. Lee, Q. Huang, V. Kiryukhin, S.-W. Cheong, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 047601.

[42] Y. Tokunaga, S. Iguchi, T. Arima, Y. Tokura, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 097205.

[43] J. Van der Brink, D. I. Khomskii, J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 434217.

[44] M. Pregelj, et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 147202.

[45] V. Caignaert, et al., Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 174403.

[46] J. K. Harada, L. Balhorn, J. Hazi, M. C. Kemei, R. Seshadri, Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 104404.

Manuscript received: October 5, 2016

Revised: November 21, 2016

Final Article published:

Communications

Magnetic Properties

A. J. Dos santos-García, \( ^{*} \)

E. Solana-Madruga,

C. Ritter ___

Large Magnetoelectric Coupling Near

Room Temperature in Synthetic

Melanostibite \( Mn_{2}FeSbO_{6} \)

Mn₂FeSbO₆ ilmenite (R3) is found to show a massive non-linear magnetoelectric coupling at 260 K, breaking local symmetry through the cationic off-centering under the application of an external magnetic field.