| Transition Temperature | 150 K |

|---|---|

| Experiment Temperature | 10 K |

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | Cmcm (#63) |

| Magnetic Space Group | P21' (#4.9) |

| Magnetic Point Group | 2' (3.3.8) |

| Lattice Parameters | 2.89060 9.80240 12.58040 90.00 90.00 90.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1038/nchem.2478 |

| Reference | S. V. Ovsyannikov, M. Bykov, E. Bykova, D. P. Kozlenko, A. A. Tsirlin, A. E. Karkin, V. V. Shchennikov, S. E. Kichanov, H. GoU, A. M. Abakumov, R. Egoavi, J. Verbeeck, C. McCammon, V. Dyadkin, D. Chernyshov, S. van Smaalen, L. S. Dubrovinsky, Nature Chemistry (2016) 8 501 - 508 |

| Label | Element | Mx | My | Mz | |M| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe1 | Fe | -1.7 | 0.0 | -3.4 | 3.80 |

| Fe2 | Fe | 1.7 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 3.80 |

| Fe3_1 | Fe | 2.2 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 4.05 |

| Fe3_2 | Fe | 2.2 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 4.05 |

Charge-ordering transition in iron oxide \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) involving competing dimer and trimer formation

Sergey V. Ovsyannikov \( ^{1*} \) , Maxim Bykov \( ^{1,2} \) , Elena Bykova \( ^{1,2} \) , Denis P. Kozlenko \( ^{3} \) , Alexander A. Tsirlin \( ^{4,5} \) , Alexander E. Karkin \( ^{6} \) , Vladimir V. Shchennikov \( ^{6,7} \) , Sergey E. Kichanov \( ^{3} \) , Huiyang Gou \( ^{1,8} \) , Artem M. Abakumov \( ^{9,10} \) , Ricardo Egoavil \( ^{9} \) , Johan Verbeeck \( ^{9} \) , Catherine McCammon \( ^{1} \) , Vadim Dyadkin \( ^{11} \) , Dmitry Chernyshov \( ^{11} \) , Sander van Smaalen \( ^{2} \) and Leonid S. Dubrovinsky \( ^{1} \)

Phase transitions that occur in materials, driven, for instance, by changes in temperature or pressure, can dramatically change the materials' properties. Discovering new types of transitions and understanding their mechanisms is important not only from a fundamental perspective, but also for practical applications. Here we investigate a recently discovered \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) that adopts an orthorhombic \( CaFe_{3}O_{5} \) -type crystal structure that features linear chains of Fe ions. On cooling below \( \sim150~K \) , \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) undergoes an unusual charge-ordering transition that involves competing dimeric and trimeric ordering within the chains of Fe ions. This transition is concurrent with a significant increase in electrical resistivity. Magnetic-susceptibility measurements and neutron diffraction establish the formation of a collinear antiferromagnetic order above room temperature and a spin canting at 85 K that gives rise to spontaneous magnetization. We discuss possible mechanisms of this transition and compare it with the trimeric charge ordering observed in magnetite below the Verwey transition temperature.

Understanding unusual transformations that occur in solids, and are accompanied by peculiar changes in atomic and electronic structures, is important for various areas of materials science, physics and chemistry \( ^{1-18} \) . The discovery of new phase transitions, as well as the reinvestigation of well-known ones by means of more-advanced characterization techniques, can reveal unexpected aspects of seemingly simple materials \( ^{2-18} \) . For example, the pressure-driven transformations of the metallic elements lithium and sodium into insulators above \( \sim60 \) and \( \sim200 \) GPa, respectively \( ^{7,8} \) , recently gave a new insight into the behaviour of elemental metals under high pressures. Oxides, industrially important materials, also demonstrate exciting phenomena under conditions that are more immediately relevant to practical applications, for instance temperature-driven 'metal-insulator'-type transitions that are widely employed in various industrial settings. Understanding the mechanisms and dynamics of such transitions is thus interesting both from a fundamental perspective and for applications, as they can directly affect the performance of devices. Detailed reinvestigation of the transitions of a metal-insulator in some key functional materials, such as vanadium oxides, \( VO_{2} \) and \( V_{2}O_{3} \) , revealed a number of unexpected features and new transient states \( ^{9-15} \) .

The oldest known magnetic mineral, magnetite \( \left(\mathrm{Fe}_{3}\mathrm{O}_{4}\right) \) , adopts a cubic spinel \( \left(\mathrm{MgAl}_{2}\mathrm{O}_{4}\cdot\mathrm{type}\right) \) structure. On cooling below \( \sim125~K \) it demonstrates a 'metal-insulator'-type transition, discovered by Verwey in 1939, at which its electrical resistivity abruptly jumps by about two orders of magnitude \( ^{1} \) . As \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) comprises both \( Fe^{2+} \) and \( Fe^{3+} \) ions, its high electrical conduction at ambient conditions is attributed to the possibility of charge transfer between \( Fe^{2+} \) (charges) and \( Fe^{3+} \) (vacancies) \( ^{1,5} \) . Consequently, this transition of \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) to an 'insulator' phase was attributed to charge ordering \( ^{1} \) . Only recently, more than 70 years after the discovery of this transition \( ^{1} \) , has the elusive charge-ordering pattern in the low-temperature phase of \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) been solved by means of single-crystal X-ray diffraction, and the charge ordering in magnetite was found to involve 'three-site distortions', called trimerons \( ^{2} \) . This picture differs drastically from the Peierls-type transition that leads to dimeric order along one-dimensional (1D) chains of metal atoms \( ^{3} \) , signatures of which may be found in many compounds.

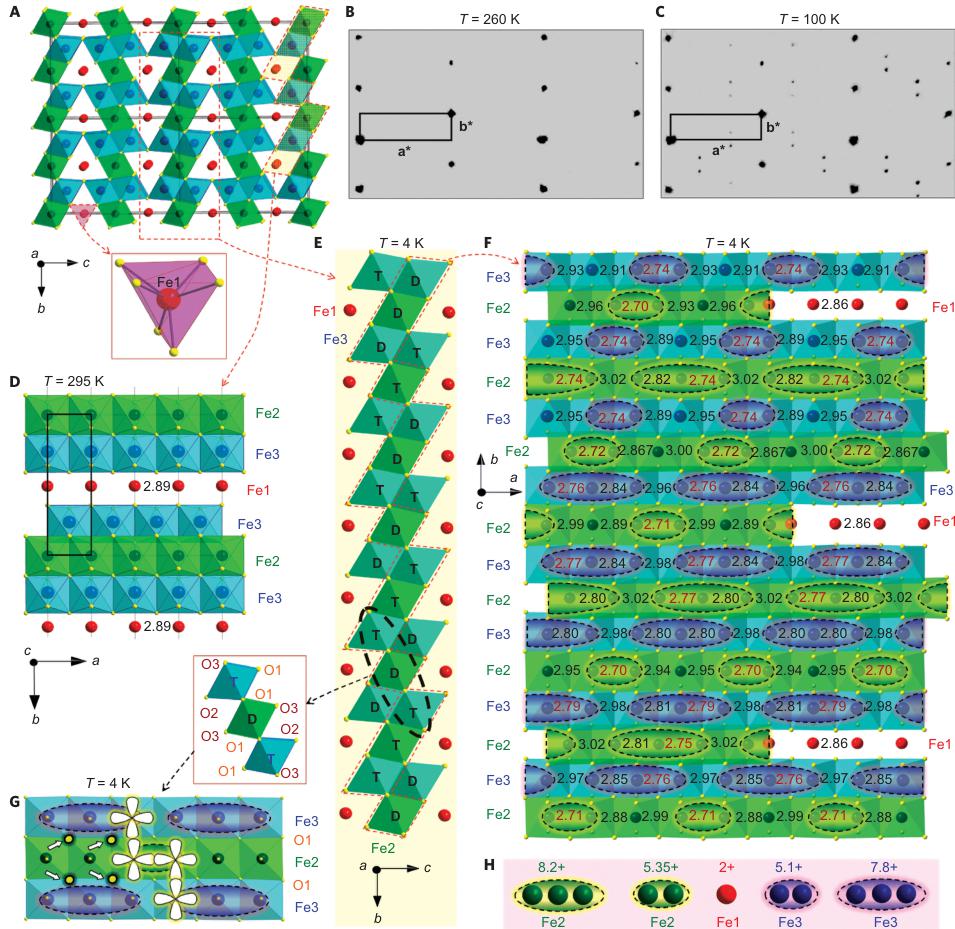

In this work, we synthesized samples of the recently discovered \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) (ref. 19) under high-pressure high-temperature conditions \( ^{20,21} \) . \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) contains equal amounts of \( Fe^{2+} \) and \( Fe^{3+} \) atoms, and in a similar manner to \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) (refs 1,2,5), it might undergo a charge ordering at relatively low temperatures. The crystal structure of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) comprises linear chains of octahedrally coordinated iron ions that occupy two slightly different crystallographic positions, Fe2 and Fe3, and linear chains of trigonal-prismatically coordinated Fe1 cations along the a axis (Fig. 1A,D). Therefore, \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) is expected to be a good model system with which we can trace the charge-ordering process. We examined \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) by means of single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Figs 1 and 2), as well as by measurements of electronic-transport properties (Fig. 3), magnetization (Fig. 4) and neutron diffraction (Fig. 5), and obtained a comprehensive picture of the charge-ordering transition at low temperatures.

Figure 1 | Crystal structure of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . A, Crystal structure projected down the a axis at room temperature. Red spheres, trigonal-prismatically coordinated Fe1 cations; green and blue spheres, octahedrally coordinated ions that occupy the two slightly different Fe2 and Fe3 crystallographic sites, respectively. The trigonal prismatic coordination environment of the Fe1 cations is shown as a purple prism (bottom). B, C, Examples of reciprocal lattices of X-ray diffraction intensities at 260 K (B) and 100 K (C). a and b are the axes of reciprocal lattices. D, Crystal structure in projection of the c axis at room temperature. The bold rectangle shows the unit cell. The numbers indicate the distances ( \( \AA \) ) between the neighbouring Fe ions along the a axis. E, F, The same part of the low-temperature crystal structure at 4 K in approximation of the nearest commensurate \( 3a \times 4b \times c' \) superstructure shown in two projections along the a axis (E) and c axis (F). These plots demonstrate the preference for dimeric (D) or trimeric (T) ordering in different chains. In the projection shown in F, the two parallel chains of each pair of Fe3 chains plotted in E overlap with each other, so we have shown only one chain. The red dashed line in E indicates those chains selected for F. In three different lines in F the parts of the Fe1 and the Fe2 chains that overlap with each other in this projection are shown. The numbers are distances ( \( \AA \) ) between the closest Fe ions. The shortest distances in this structure are highlighted in red. All the Fe1–Fe1 distances are the same ( \( \sim \) 2.861 \( \AA \) ). G, Example of a three-chain ribbon with shared edges highlighted by the dashed ellipsoid in E. The inset above G labels all the oxygen atoms of this ribbon. The O1 oxygen sites (marked by arrows) that neighbour the central Fe ions in the trimers potentially might be 'underbonded'. The minority-spin d orbitals of the Fe ions within such planes have the same spatial symmetry (as examples, the d orbitals of four Fe ions are shown in white). H, Typical BVSs of the dimers and trimers at 4 K.

Results and discussion

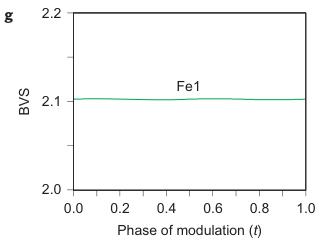

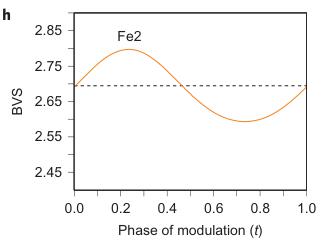

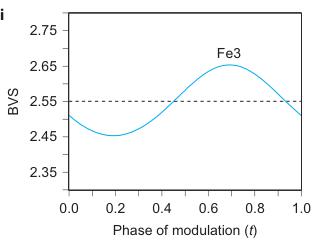

Crystal structure of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . At ambient conditions, \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) crystallizes in the orthorhombic \( CaFe_{3}O_{5} \) -type Cmcm structure, which contains three different sites for Fe ions (Fig. 1A,D and Supplementary Table 1) \( ^{19,22} \) . To evaluate the oxidation states of different Fe ions in this structure, we applied a bond-valence-sum (BVS) approach (see Methods for the details) \( ^{23} \) and found the oxidation states of Fe1, Fe2 and Fe3 to be +1.92, +2.76 and +2.66, respectively. This charge distribution was confirmed by electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) (Supplementary Fig. 1). The above estimations suggest that the Fe1 sites are filled exclusively by \( Fe^{2+} \) ions, whereas the Fe2 and Fe3 sites are mixed valent, featuring both \( Fe^{2+} \) and \( Fe^{3+} \) ions. This

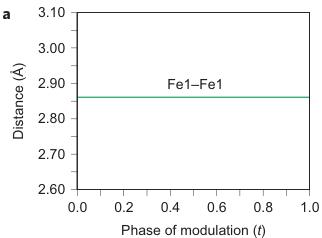

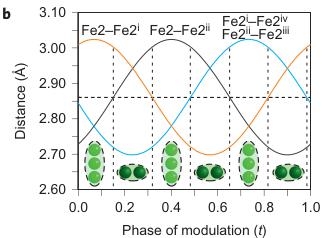

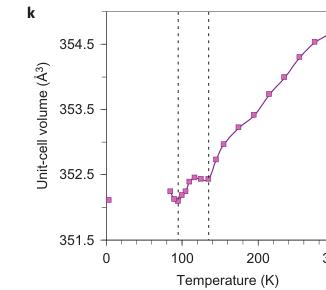

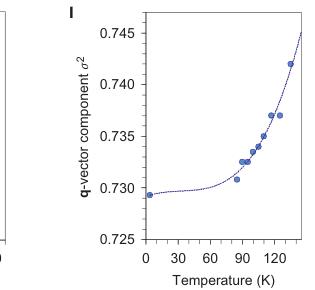

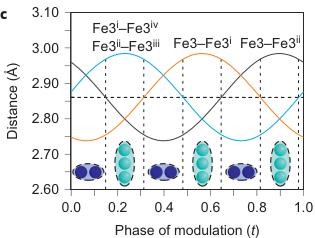

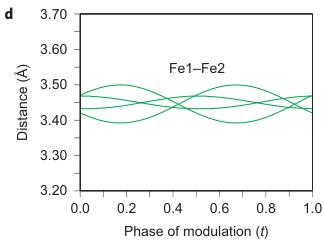

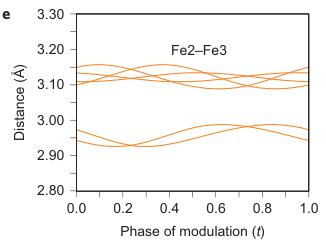

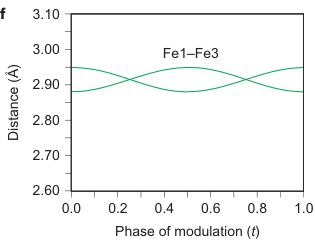

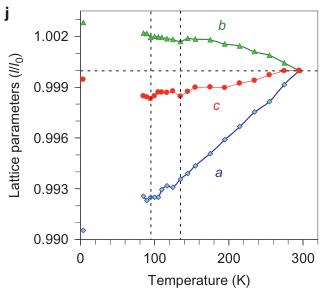

Figure 2 | Crystal structure parameters of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . a–f. The closest distances between the Fe ions calculated from the crystal structure at 4 K: Fe1–Fe1 (a), Fe2–Fe2 (b), Fe3–Fe3 (c), Fe1–Fe2 (d), Fe2–Fe3 (e) and Fe1–Fe3 (f). The reference distance, Fe1–Fe1 ≈ 2.861 Å, is shown in b and c as a horizontal dashed line. The upper indices in b and c denote different symmetry codes: (i) \( (x+1) \) , \( y \) ; (ii) \( (x-1) \) , \( y \) ; (iii) \( (x-2) \) , \( y \) ; and (iv) \( (x+2) \) , \( y \) , where x, y and z are the relative atomic coordinates (Supplementary Table 4). These plots demonstrate the formation of dimers (one short and two long distances) and trimers (two short and one long) in the Fe2 and Fe3 chains. We have labelled these areas in the plots by visual representations. One can see in b and c that the distances between the Fe ions in the dimers and trimers can vary smoothly through the crystal structure. g–i, BVSs of the Fe ions at 4 K: Fe1 (g), Fe2 (h) and Fe3 (i). j–l Temperature dependence of lattice parameters (j), unit-cell volume (k) and the incommensurate q-vector component, \( \sigma_{2} \) (l). The data in j–l represent a combination of results of two experiments from 300 down to 80 K and at 4 K. The vertical dashed lines indicate two crossovers.

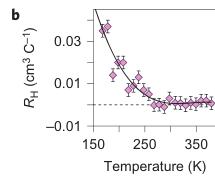

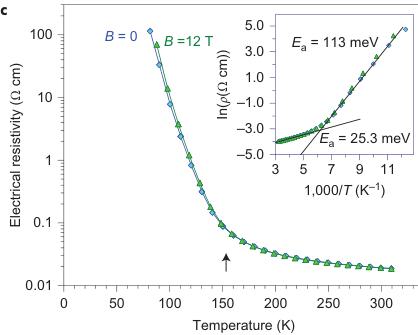

picture indicates a possibility of charge transfer between \( Fe^{2+} \) and \( Fe^{3+} \) ions that occupy the octahedral sites, in a similar manner to other Fe-bearing oxides, including magnetite \( ^{1,2} \) . Therefore, like magnetite \( ^{1} \) , \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) is expected to have a high concentration of charge carriers, which results from the high concentrations of available charges ( \( Fe^{2+} \) ) and vacancies ( \( Fe^{3+} \) ) at the octahedral sites in the structure. Electronic properties of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . We examined the electronic properties of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) by measurements of the electrical resistivity and the Hall effect (see Methods) of a bulk quasi-single-crystalline sample (Fig. 3). The temperature dependence of the electrical resistivity, \( \rho(T) \) , demonstrates a semiconducting-like behaviour (Fig. 3c) and has an activation character, which

Figure 3 | Electronic properties of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . a, A photograph of a large quasi-single-crystal of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . b, Temperature dependence of the Hall constant, \( R_{H} \) , measured in a magnetic field of 12 T (the error bars show the potential average uncertainties related to a noise contribution to the signal, experimentally determined for several temperature points). In a similar way to \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) (ref. 24) and \( Fe_{2}O_{3} \) (ref. 27), the measured Hall effect of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) might also include some contribution of the extraordinary Hall effect that arises from non-zero magnetization in an applied magnetic field, but an investigation of this effect was beyond the scope of our present work. c, Temperature dependence of electrical resistivity of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) at 0 and 12 T magnetic fields. These curves exhibit a bend at 150 K (shown by the arrow), which indicates a transition between the states with a high and a low electrical conduction (that is, of the 'metal-insulator' type). The inset in c shows a determination of \( E_{a} \) in the both phases. The \( E_{a} \) values of these states were found to be \( E_{a} = 25.3 \) and 113 meV above and below 150 K, respectively. The electrical resistivity curves (c) show a noticeable positive magnetoresistance effect below 150 K, but this effect requires further investigation beyond the scope of this work.

suggests that the resistivity decreases with temperature as a function of \( \rho\approx\exp[E_{a}/(kT)] \) (inset in Fig. 3c), where \( E_{a} \) is the activation energy (the energy that is required to activate either the charge carriers over the bandgap into the conduction band, or the carrier mobility enabling the existing charge carriers to contribute to electrical conduction), k is Boltzmann's constant and T is the temperature. The dramatic increase in the electrical resistivity below 150 K (Fig. 3c) resembles that of the Verwey transition in magnetite \( ^{1} \) , although the transition in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) looks more continuous.

At ambient conditions, \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) has an \( E_{a} \) of \( \sim25 \) meV (inset in Fig. 3c). It is interesting that materials with a semimetal conductivity can also exhibit an activation dependence on electrical resistivity, for example, magnetite demonstrated \( E_{a} \) values of 14 meV (ref. 24) or 0.1 eV (ref. 25) in single- or polycrystalline samples, respectively. As discussed in previous works \( ^{[24,26,27]} \) , the charge carrier mobility in \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) and \( \alpha-Fe_{2}O_{3} \) is rather low, less than \( \sim0.1~cm^{2}~V^{-1}~s^{-1} \) , and hence \( E_{a} \) values should be attributed mainly to mobility activation, which suggests a progressive increase in carrier mobility, but not to carrier activation over the bandgap. Measurements of the Hall effect (see Methods) in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) showed a very low value at room temperature, which suggests a metallic carrier concentration above \( 10^{21}~cm^{-3} \) , although a precise estimate is not possible at the moment (Fig. 3b). The Hall effect slightly increased as temperature decreased and showed positive values, which suggest p-type conduction (Fig. 3b). Magnetite is known to be a half metal that demonstrates a good conductivity to electrons of one spin orientation, but poor conductivity to electrons of the opposite orientation \( ^{[28-30]} \) and, taking into account certain similarities between \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) and \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) , we cannot exclude half-metallic conduction in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) , but this point requires further investigation. The low-temperature phase of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) has an \( E_{a}\sim113~meV \) , which suggests an energy bandgap, \( E_{g} \) , of \( 2E_{a}=0.226~eV \) (Fig. 3c, inset), which is larger than the reported bandgap in the Verwey phase of magnetite, \( E_{g}\leq0.1~eV \) (ref. 31).

Low-temperature crystal structure of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . On cooling below 150 K, single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies detected the appearance of superlattice reflections (Fig. 1B,C) indicating the appearance of a new structural order that was superimposed on the persisting initial crystal structure. Intensities of these reflections grow with decreasing temperature (Supplementary Fig. 2). Indexing these superlattice reflections demonstrated that this structure is incommensurately modulated. In other words, this is a modulated structure in which atoms suffer certain periodical deviations from positions they would take in a hypothetical 'average' (basic) non-modulated structure, and a period of these fluctuations is incommensurate with at least one of the periodicities in the 3D unit cell. These structural fluctuations in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) are determined by the modulation wave vector, \( q = \sigma_{1}a^{*} + \sigma_{2}b^{*} \) , where \( a^{*} \) and \( b^{*} \) are the axes of reciprocal lattices shown in Fig. 1B,C, and \( \sigma_{1} = 1/3 \) and the temperature-dependent \( \sigma_{2} \) are components of this vector. We solved this structure and determined its superspace group as \( C2_{1}/m(\sigma_{1}\sigma_{2}0)0s \) (standard setting \( P2_{1}/m(\sigma_{1}\sigma_{2}0)0s \) . No. 11.1.2.2) \( ^{32} \) (see the Supplementary Information, which includes Crystallographic Information Files). At 4 K, we found the lattice parameters to be \( a = 2.8610(4) \) Å, \( b = 9.8123(5) \) Å, \( c = 12.5425(11) \) Å, \( \gamma = 90.0(1)^{\circ} \) , \( V = 352.10(6) \) Å \( ^{3} \) and \( \sigma_{2} = 0.7293(13) \) (Supplementary Table 2). The parameter \( \sigma_{2} \approx 0.7293(13) \) of the modulation wave vector is irrational and, hence, a period of the structural modulations along the b axis cannot be proportional to the unit-cell parameter b and, therefore, the crystal structure is incommensurately modulated.

The largest displacements of the Fe ions in the low-temperature structure of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) relative to their positions in the 'average' (basic) non-modulated structure were along the a axis (Supplementary Fig. 3). As incommensurately modulated structures cannot be visualized in crystallographic software, to investigate the details of this low-temperature structure we used the nearest commensurately modulated crystal structure with \( \sigma_{2}=3/4 \) (instead of \( \sigma_{2}\approx0.73 \) ), and hence, with a q vector (1/3, 3/4, 0) that corresponds to a \( \langle3a\times4b\times c\rangle \) lattice (Fig. 1F). With JANA2006 software (see Methods) we plotted the Fe–Fe distances and the BVSs of the Fe ions at 4 K (Fig. 2a–i). On cooling, the lattice parameters of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) , determined from the single-crystal X-ray diffraction data, demonstrated several interesting features in their temperature dependence, in particular sharp bends at 135 K, 115 K and below 90 K (Fig. 2j,k). The anomalies in the unit-cell volume below 90 K resemble those reported earlier for the Verwey transition in magnetite \( ^{33} \) . Unusual electronic transitions can lead to very peculiar volumetric effects—this has, for example, been observed with an inter-site charge transfer in \( LaCu_{3}Fe_{4}O_{12} \) , which results in a negative thermal expansion \( ^{34} \) .

The main characteristics of the transition in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) at 150 K involve the formation of Fe dimers and trimers within the chains of Fe2 and Fe3 ions along the a axis (Fig. 1F), with the chains of ferrous Fe1 ions only weakly modulated along the c axis (Supplementary Fig. 3). A constant Fe1–Fe1 distance in the low-temperature structure ( \( \sim2.861 \) Å at 4 K) (Fig. 2a) served as a reference point, which enabled us to deduce the significant

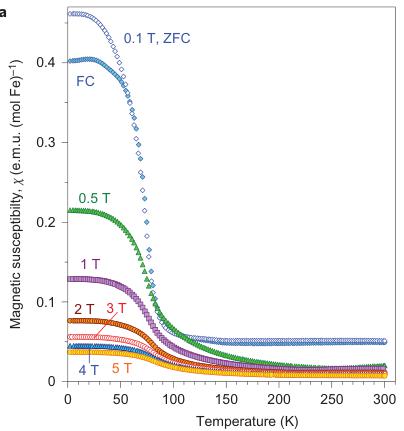

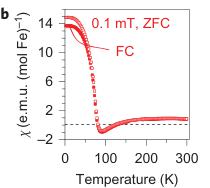

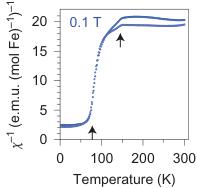

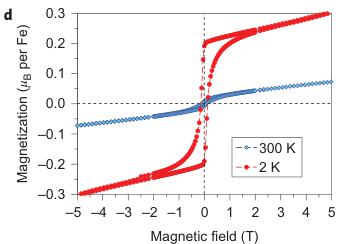

Figure 4 | Magnetic properties of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . a, Temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility \( \chi \) of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) measured at different magnetic fields under both field-cooling (FC) and zero-field-cooling (ZFC) conditions. b, Temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility measured in a magnetic field of 0.1 mT. c, Reciprocal magnetic susceptibility measured in a magnetic field of 0.1 T from a. These curves indicate two crossovers, near 150 and 75 K (indicated by the arrows). A weak downturn around 150 K marks the structural and electronic phase transitions (Fig. 3c). d, Magnetization curves measured at 2 and 300 K. These magnetic studies were performed on bulk polycrystalline samples, and hence we cannot exclude the presence of a minor impurity of unreacted \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) that would also induce weak ferromagnetic behaviour up to room temperature.

shortening of some Fe2–Fe2 and Fe3–Fe3 distances (Fig. 1F, marked by elongated ellipsoids, and Fig. 2b,c). As seen in Fig. 1F, each chain of Fe2 or Fe3 ions contains either dimers or trimers and, as seen from Fig. 2b,c, the overall numbers of dimers and trimers throughout the crystal structure are roughly equal.

Using data of Fe–O bond lengths at 4 K (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3) we estimated the BVSSs (Fig. 2g–i). A small non-equivalence in these BVSSs between the Fe2 and Fe3 sites found at 295 K (+2.76 vs +2.66, respectively) also persisted in the low-temperature phase (Fig. 2h,i). This hints that the charge carriers ( \( Fe^{2+} \) ) have a slight preference for the Fe3 sites, and for this reason the Fe3 chains could have less charge than the Fe2 ones (Fig. 2h,i). This is also shown by comparison of the BVSSs of dimers and trimers in the Fe2 and Fe3 chains (Fig. 1H). The BVS analysis shows that the trimers are, in general, composed of one \( Fe^{2+} \) and two \( Fe^{3+} \) ions (Fig. 1H), similar to the trimers in \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) (ref. 2). Similarly, the Fe ions in the dimers in the Fe3 chains have an oxidation state close to +2.5, thereby indicating that the dimers are \( Fe^{2+}-Fe^{3+} \) pairs with one shared electron. However, the dimers in the Fe2 chains seem a bit overcharged—their average charge, +5.35, is notably higher than that of the dimers in the Fe3 chains, +5.1 (Fig. 1H). Meanwhile, as seen from a comparison of Fig. 2h and Fig. 2i, the charge density waves along the Fe2 and Fe3 chains are in opposite phases of modulation, which suggests a nearly uniform charge distribution in the lattice. In contrast to these intricate changes in the Fe2 and Fe3 chains across the phase transition, the BVSSs of the Fe1 ions (Fig. 2g) and the distances between them (Fig. 2a) remained equal, thereby demonstrating that the low-temperature transition is driven by the charge ordering and, hence, the Fe1 chains remain inactive in this transition.

As can be seen in Fig. 2d–f, the minimal Fe1–Fe2, Fe2–Fe3 and Fe1–Fe3 distances at T = 4 K do not exhibit any significant shortening along the c and b axes when compared with the aforementioned reference distance of \( \sim \) 2.861 Å. This indicates that the transition in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) can be considered as a quasi-1D charge ordering in the Fe2 and Fe3 chains, which leads to the formation of both dimers in some chains and trimers in the others (Fig. 1F). Each 1D chain has an individual set of the Fe–Fe distances that obey the threefold period ( \( \sigma_{1} = 1/3 \) ). X-ray diffraction images collected below 150 K show an appreciable diffuse scattering (Supplementary Fig. 5) that could be related to additional structural effects at the local level, but these go beyond the scope of our present work.

Magnetic properties of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . The magnetic properties of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) were examined by magnetic-susceptibility and neutron-diffraction studies on bulk polycrystalline samples. We observed weak ferromagnetism up to room temperature, with the remnant magnetization of \( \sim0.02\ \mu_{B} \) per Fe at 300 K (Fig. 4d). This behaviour resembles that of haematite ( \( \alpha-Fe_{2}O_{3} \) ), which is a weak ferromagnet with a tiny magnetic moment of \( \sim0.002\ \mu_{B} \) per Fe at room temperature \( ^{35} \) because of the weak spin canting, which consists in the tilting of spins by a small angle away from the collinear configuration, on top of the collinear antiferromagnetic ordering. This resemblance suggests that it may be the case in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) as well. A more-pronounced and clearly intrinsic ferromagnetic signal is seen below \( \sim90\ K \) (Fig. 4a–c), and at 2 K the magnetization saturates to \( \sim0.2\ \mu_{B} \) per Fe (Fig. 4d). Thus, these data indicate that below 85–90 K, \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) is a canted antiferromagnet, that is, an antiferromagnet in which the spins are tilted by a small angle away from the collinear configuration and do not fully compensate each other, which leads to such a non-zero magnetic moment. The abrupt growth in the magnetization below 90 K (Fig. 4a–c) correlates with the anomaly detected in the lattice parameters below 90 K (Fig. 2j,k).

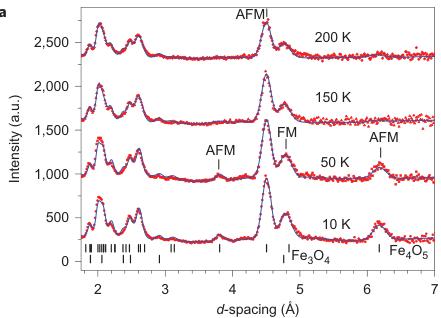

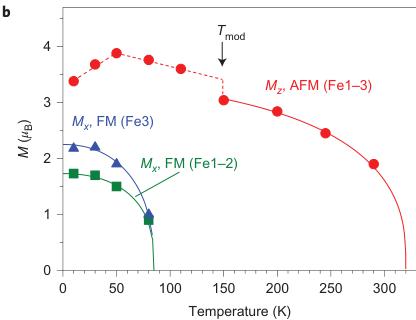

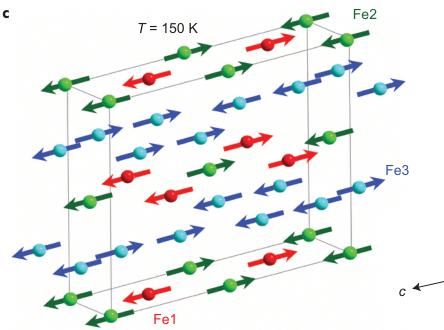

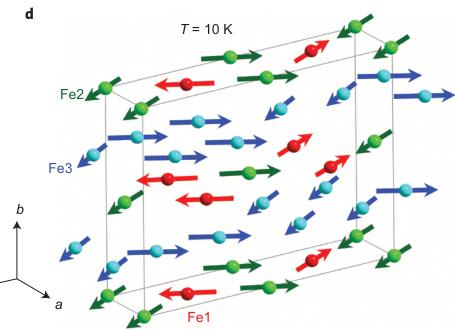

Neutron diffraction showed that magnetic order was already present at room temperature. This magnetic order resulted in the growth of the \( (021) \) peak at \( d=4.51\ \AA \) which has a negligible contribution from the nuclear structure (Fig. 5a). Magnetic moments of the Fe ions are directed along the c axis and are ordered antiferromagnetically (Fig. 5b,c). From the powder data we can neither exclude nor confirm a weak spin canting at room temperature. To reduce the number of refinable parameters, we constrained the ordered magnetic moments of the Fe ions located at different sites to be equal. From the temperature dependence of magnetic

Figure 5 | Magnetic structure of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . a, Temperature evolution of neutron-diffraction patterns of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . The dashes above the x axis correspond to the expected reflection positions for \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) (upper row) and \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) (lower row). a, arbitrary units. b, Temperature dependence of the average \( M_{z} \) (AFM, antiferromagnetic) and \( M_{x} \) (FM, ferromagnetic) components of the Fe spins. These dependences demonstrate two effects: (1) the spin canting below \( T_{SC} = 85 \) K from the c towards the a axis and (2) an abrupt increase in the ordered magnetic moment at the lattice modulation temperature, \( T_{mod} = 150 \) K. c, d, Long-range magnetic order in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) above (c) and below (d) the spin-canting temperature. The arrows indicate the orientations of the Fe spins in different crystallographic positions, of which labels and colours correspond to those in Fig. 1. For simplicity we show the unit-cell edges that correspond to the crystal structure at ambient conditions. In the actual incommensurate low-temperature structure the Fe ions are slightly shifted (Figs 1f and 2a-c).

moments, we estimated the antiferromagnetic transition temperature as \( T_{N} \approx 320 \) K (Fig. 5b). Near 150 K, we detected an abrupt increase in the average ordered magnetic moment by \( \sim0.5 \mu_{B} \) (Fig. 5b). This effect correlates with the structural modulation and ensuing changes in electronic-density distribution. Near \( T_{SC} = 85 \) K, we found another magnetic transition that was attributed to spin canting of the ordered magnetic moments towards the a axis (Fig. 5d). This rearrangement in the magnetic structure resulted in the appearance of ferromagnetic components ( \( M_{x} \) ) that gave rise to two magnetic peaks, (002) at \( d = 6.19 \AA \) and (022) at \( d = 3.81 \AA \) (Fe1 and Fe2 sublattices) and contributed to the (020) nuclear peak at \( d = 4.84 \AA \) (Fe3 sublattice). The ferromagnetic components of the Fe1 and Fe2 magnetic sublattices are antiparallel, and thus compensate each other (Fig. 5d). In contrast, the ferromagnetic component of the Fe3 sublattice remains uncompensated, which leads to the remnant magnetization observed below \( T_{SC} \) (Fig. 4).

The lattice of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) was found to exhibit very different axial compressibilities (Fig. 2j). The magnetic order can give insight into these peculiarities. Thus, negative thermal expansion along the b axis (Fig. 2j) may be related to the antiferromagnetic spin arrangement along this direction (Fig. 5c,d). Antiparallel spins will generally tend to increase the antiferromagnetic exchange energy by expanding Fe–Fe distances and, hence, by increasing Fe–O–Fe angles that play a crucial role in this superexchange. Similar effects were reported for \( CuF_{2} \) (ref. 36) and \( SrCu_{2}(BO_{3})_{2} \) (ref. 37). Progressive shrinkage along the a axis with decreasing temperature (Fig. 2j) suggests an enhancing role of the a axis in the charge transfer and Fe–Fe interactions at lower temperatures and could explain the quasi-1D character of the charge-ordering transition.

The low-temperature transition. The charge ordering in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) is preceded by the magnetic transition that imposes a ferromagnetic spin arrangement along the a direction (Fig. 5d). The electronic configuration of \( Fe^{2+} \) ions is \( 3d^{6} \) , so that in the high-spin state five electrons adopt one spin direction, and the sixth electron adopts the opposite spin direction to form the minority-spin channel. Below the Verwey transition temperature, the spins of Fe ions that form trimers in \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) are aligned ferromagnetically \( ^{33,38} \) , and the minority-spin electron of one \( Fe^{2+} \) ion can be shared with two neighbouring \( Fe^{3+} \) ions \( ^{2} \) . This process is facilitated by weak axial distortion of \( FeO_{6} \) octahedra, which introduces an additional crystal-field splitting and defines the position of the lowest-energy \( t_{2g} \) orbital to host this minority-spin electron of \( Fe^{2+} \) . Then, three atoms that share the same plane of this lowest-energy orbital form a trimeron \( ^{2} \) . Thus, the charge-ordering pattern is related to the connectivity of \( FeO_{6} \) octahedra.

The ferromagnetic order along the a direction renders a similar mechanism operative in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . Both the Fe2 and Fe3 octahedra in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) showed a noticeable axial compression that splits the three \( t_{2g} \) levels of Fe ions in a regular \( FeO_{6} \) octahedron into the lower-lying

singlet and higher-lying doublet. The lowest-energy orbital that can be occupied by the minority-spin electron lies in the plane that is shared by all the octahedra of one chain (Fig. 1E,G). The same plane is also shared by two contiguous chains, and together they form a structural ribbon that comprises one Fe2 chain encompassed by two Fe3 chains (Fig. 1G). Alternation of dimers and trimers throughout the crystal structure may be understood by considering such diagonal ribbons (Fig. 1E,G) in which two chains form the trimers and one chain forms the dimers, or the other way around. The dimers (D) are always formed in the space 'between' trimers (T), as illustrated in Fig. 1G. For the opposite case of 'D-T-D' ribbons, which, for example, surround this selected 'T-D-T' ribbon (Fig. 1E), the dimers in the Fe3 chains are always formed in the space between trimers in the central Fe2 chain (see the third to fifth upper chains in Fig. 1F). The simultaneous formation of dimers and trimers and their nearly perfect alternation in these ribbons might be linked, for instance, to a peculiar type of bonding of O1 oxygen atoms shared by the Fe2 and Fe3 chains (Fig. 1G). If only dimers or only trimers are formed, these O1 oxygen atoms (labelled by arrows in Fig. 1G) might become 'over-bonded' (that is, their effective valence might become higher than two) or 'underbonded' (that is, with an effective valence smaller than two), respectively. Other factors, such as elastic coupling between Fe2 and Fe3 chains through O1 atoms located between these chains within each ribbon, could also affect the ordering pattern. Thus, the formation of dimers in the space between trimers (or the other way around) partly compensates the lattice distortions that arise from the formation of trimers (Fig. 1F,G).

Conclusions

In summary, we showed that at 150 K, \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) undergoes a phase transition that involves the simultaneous formation of dimers and trimers within linear chains of octahedrally coordinated Fe ions. This unexpected charge ordering gives rise to unusual modulations in the crystal structure. The underlying mechanism of the charge ordering in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) may be, to some extent, similar to that in magnetite \( ^{2} \) , but the different nature of the crystal structure results not only in the formation of trimers, but also in that of dimers, present in approximately equal numbers throughout the crystal structure. Unlike the Verwey transition in magnetite, which has a 3D character \( ^{2} \) , the charge ordering in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) looks like a quasi-1D transition. For \( Fe_{2}OBO_{3} \) , a charge ordering that involves the ordering of localized charges without sharing electrons within dimers or trimers also led to an incommensurate phase \( ^{39} \) . The coexistence of dimers and trimers in \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) at low temperatures may be related to a peculiar structural connectivity and elastic coupling between Fe chains.

Methods

Preparation and characterization of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . The samples of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) were synthesized in 1,200 tonne Multi-Anvil Presses at the Bayerisches Geoinstitut. We explored several synthesis routes to fabricate this polymorph. The best and simplest path we found was a direct synthesis from a mixture of \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) (Aldrich, 99.99% purity) and Fe (99.99%) that corresponded to \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) stoichiometry at conditions of 11–14 GPa and 1,000–1,300 °C. We employed a standard assembly, which included a Re capsule, \( LaCrO_{3} \) heater, W3Re/W25Re thermocouples and an octahedral container \( ^{40} \) ; the procedure was similar to that described before \( ^{20,21} \) . Typical synthesis times were about 1–4 hours. This \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) polymorph is readily recoverable at ambient conditions and remains (meta)stable if not overheated above 150 °C (ref. 41). It is also stable under the application of high pressures of at least up to 40 GPa (refs 19,42). The chemical composition of the samples was examined by scanning electron microscopy with a LEO-1530 instrument and by microprobe analysis with a JEOL JXA-8200 electron microprobe. The purity and the stoichiometry of the samples were verified. Also, doped modifications of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) may be prepared routinely from magnetite (for example, those reported doped with Cr and Mg) \( ^{43-45} \) .

The sample for the transmission electron microscopy investigation was prepared by crushing the material, dispersing it in ethanol and depositing it onto a holey carbon grid. EELS measurements were performed using a FEI Titan3 80-300 transmission electron microscope operated at 300 kV. A monochromator was used to optimize the energy resolution for the EELS measurements to 250 meV. The EELS spectra were fitted using the EELSMODEL program (www.eelsmodel.ua.ac.be) \( ^{46} \) . EELS spectra of the Fe L \( _{2,3} \) excitation edge combined with a model-based fitting to reference spectra for Fe \( ^{2+} \) and Fe \( ^{3+} \) were used to measure the oxidation state of the Fe cations. We obtained a mixed-valence condition of 53(4)% Fe \( ^{2+} \) and 47(4)% Fe \( ^{3+} \) . Details of the collection treatment of the EELS spectra are given in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . At ambient conditions the crystal structure of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) was determined from single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies using a four-circle Oxford Diffraction Xcalibur diffractometer ( \( \lambda = 0.71073 \AA \) ) equipped with an Xcalibur Sapphire2 CCD (charge-coupled device) detector (details are available in the Supplementary Information). High-quality single crystals were selected for temperature-dependent single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies. In one experiment we studied temperature-dependent X-ray diffraction using a Mar345dtb diffractometer equipped with a MAR345 image plate detector from 295 to 80 K. For the lattice-parameter determination, the series of \( \varphi \) scans (60 frames, \( \Delta\varphi = 1^{\circ} \) , exposure time = 60 s deg \( ^{-1} \) ) were measured at different temperatures and processed with the CryAsIisPro software package. For each temperature point the same part of reciprocal space was covered, which thus gave equal sets of diffraction peaks used for the orientation matrix refinement. Another experiment with full data collection was carried out at SNBL (The Swiss-Norwegian Beam Line, European Synchrotron Radiation Facility) with a wavelength of 0.6884 Å at the lowest temperature of 4 K. Intensity data were collected on a single-axis diffractometer equipped with a Pilatus 2M pixel detector by \( 360^{\circ} \varphi \) scans ( \( \Delta\varphi = 1^{\circ} \) ). Data processing (peak-intensities integration, background evaluation, cell parameters and absorption correction) was done with the CryAsIisPro 171.36.28 program. The structure was solved by SUPERFILP \( ^{47} \) employing a charge-flipping algorithm in superspace. Structure refinements were performed with the JANA2006 crystallographic computing system \( ^{48} \) .

To evaluate the oxidation states of different Fe ions in the crystal structure we applied a BVS method \( ^{23} \) based on the analysis of Fe–O bond lengths around the Fe ions. In this method the oxidation state of an ion \( (V_{i}) \) is the sum of all its bond valences \( (S_{ij}) \) , each of which is determined as \( S_{ij} = \exp((R_{ij} - d_{ij})/b_{0}) \) , where \( d_{ij} \) is the distance between atoms i and j, \( R_{ij} \) is the empirically determined distance for this cation–anion pair and \( b_{0} \) is an empirical parameter, which is normally about 0.37 Å (ref. 23).

Measurements of the electronic-transport and magnetic properties of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . Electronic-transport properties (Fig. 3) were measured by the conventional Montgomery method using an Oxford Instruments set-up. We measured the temperature dependence of electrical resistivity and the Hall effect. The Hall effect consists of the appearance of a voltage difference in the direction perpendicular to both the electrical current in a conductor and the applied magnetic field, which is also directed perpendicular to this electrical current.

Magnetic susceptibility (Fig. 4) was measured with a Quantum Design MPMS SQUID magnetometer in the temperature range 2–380 K in applied fields up to 5 T under both field-cooling (FC) and zero-field-cooling (ZFC) conditions.

Neutron-diffraction studies of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . The magnetic structure of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) was investigated using a DN-12 neutron diffractometer to study microsmaps \( ^{49} \) at the IBR-2 high-flux pulsed reactor (Frank Laboratory of Neutron Physics). A sample with a volume about \( 1.5 \, mm^{3} \) was placed inside a cryostat based on a closed-cycle refrigerator. The neutron powder diffraction data were collected at scattering angles of \( 2\theta = 45.5 \) and \( 90^{\circ} \) . The measurements were performed in the temperature range 10–300 K. The data were analysed by the Rietveld method using the Fullprof program \( ^{50} \) . Possible models of magnetic structure were considered, taking into account the symmetry analysis performed by the Baslreps program (https://www.ill.eu/sites/fullprof/).

Data availability. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for the structure of \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) at 4 K are deposited at the Bilbao Incommensurate Structures Database, under the deposition number 11512ETwLZ1.

Received 5 March 2015; accepted 15 February 2016; published online 4 April 2016

References

-

Verwey, E. J. W. Electronic conduction of magnetite ( \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) ) and its transition point at low temperatures. Nature 144, 327–328 (1939).

-

Senn, M. S., Wright, J. P. & Atfield, J. P. Charge order and three-site distortions in the Verwey structure of magnetite. Nature 481, 173–176 (2012).

-

Peierls, R. E. Quantum Theory of Solids (Oxford Univ. Press, 1955).

-

Mott, N. F. Metal–insulator transition. Rev. Mod. Phys. 40, 677–683 (1968).

-

Mott, N. F. Metal–Insulator Transitions (Taylor and Francis Ltd, 1974).

-

Imada, M., Fujimori, A. & Tokura, Y. Metal insulator transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039–1263 (1998).

-

Matsuoka, T. & Shimizu, K. Direct observation of a pressure-induced metal-to-semiconductor transition in lithium. Nature 458, 186–189 (2009).

-

Ma, Y. et al. Transparent dense sodium. Nature 458, 182–185 (2009).

-

Limelette, P. et al. Universality and critical behavior at the Mott transition. Science 302, 89–92 (2003).

-

Qazilbash, M. M. et al. Mott transition in \( VO_{2} \) revealed by infrared spectroscopy and nano-imaging. Science 318, 1750–1753 (2007).

-

Nakano, M. et al. Collective bulk carrier delocalization driven by electrostatic surface charge accumulation. Nature 487, 459–462 (2009).

-

Driscoll, T. et al. Memory metamaterials. Science 325, 1518–1521 (2009).

-

Lupi, S. et al. A microscopic view on the Mott transition in chromium-doped \( V_{2}O_{3} \) . Nature Commun. 1, 105 (2010).

-

Budai, J. D. et al. Metallization of vanadium dioxide driven by large phonon entropy. Nature 515, 535–539 (2014).

-

Morrison, V. R. et al. A photoinduced metal-like phase of monoclinic \( VO_{2} \) revealed by ultrafast electron diffraction. Science 346, 445–448 (2014).

-

de Jong, S. et al. Speed limit of the insulator–metal transition in magnetite. Nature Mater. 12, 882–886 (2013).

-

Neaton, J. B. & Ashcroft, N. W. Pairing in dense lithium. Nature 400, 141–144 (1999).

-

Neaton, J. B. & Ashcroft, N. W. On the constitution of sodium at higher densities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 2830–2833 (2001).

-

Lavina, B. et al. Discovery of the recoverable high-pressure iron oxide \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17281–17285 (2011).

-

Ovsyannikov, S. V. et al. Perovskite-like \( Mn_{2}O_{3} \) : a path to new manganites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 1494–1498 (2013).

-

Ovsyannikov, S. V. et al. A hard oxide semiconductor with a direct and narrow bandgap and switchable p–n electrical conduction. Adv. Mater. 26, 8185–8191 (2014).

-

Gerardin, R., Millon, E., Brice, J. F., Evrard, O. & Le Caer, G. Transfert lelectronique d'intervalence entre sites inequivalents: étude de \( CaFe_{3}O_{5} \) par spestrometrie Müsbauer. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 46, 1163–1171 (1985).

-

Brese, N. E. & O'Keeffe, M. Bond-valence parameters for solids. Acta Cryst. B 47, 192–197 (1991).

-

Shchennikov, V. V., Ovsyannikov, S. V., Karkin, A. E., Todo, S. & Uwatoko, Y. Galvanomagnetic properties of fast neutron bombarded \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) magnetite: a case against charge ordering mechanism of the Verwey transition. Solid State Commun. 149, 759–762 (2009).

-

Morris, E. R. & Williams, Q. Electrical resistivity of \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) to 48 GPa compression-induced changes in electron hopping at mantle pressures. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 139–148 (1997).

-

Morin, F. J. Electrical properties of \( \alpha \) - \( Fe_{2}O_{3} \) . Phys. Rev. 93, 1195–1199 (1954).

-

Ovsyannikov, S. V., Morozova, N. V., Karkin, A. E. & Shchennikov, V. V. High-pressure cycling of hematite \( \alpha \) - \( Fe_{2}O_{3} \) : nanostructuring, in situ electronic transport, and possible charge disproportionation. Phys. Rev. B 86, 205131 (2012).

-

Dedkov, Y. S., Rüdiger, U. & Güntherodt, G. Evidence for the half-metallic ferromagnetic state of \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) by spin-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 65, 064417 (2002).

-

Fonin, M., Dedkov, Y. S., Pentcheva, R., Rüdiger, U. & Güntherodt, G. Magnetite: a search for the half-metallic state. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 19, 315217 (2007).

-

Müller, G. M. et al. Spin polarization in half-metals probed by femtosecond spin excitation. Nature Mater. 8, 56–61 (2009).

-

Chainani, A., Yokoya, T., Morimoto, T., Takahashi, T. & Todo, S. High-resolution photoemission spectroscopy of the Verwey transition in \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) . Phys. Rev. B 51, 17976–17979 (1995).

-

Stokes, H. T., Campbell, B. J. & van Smaalen, S. Generation of \( (3+\mathrm{d}) \) -dimensional superspace groups for describing the symmetry of modulated crystalline structures. Acta Crystallogr. A 67, 45–55 (2011).

-

Wright, J. P., Bell, A. M. T. & Attfield, J. P. Variable temperature powder neutron diffraction study of the Verwey transition in magnetite \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) . Solid State Sci. 2, 747–753 (2000).

-

Long, Y. W. et al. Temperature-induced A–B intersite charge transfer in an A-site-ordered \( LaCu_{3}Fe_{4}O_{12} \) perovskite. Nature 458, 60–63 (2009).

-

Morin, F. J. Magnetic susceptibility of \( \alpha-Fe_{2}O_{3} \) and \( \alpha-Fe_{2}O_{3} \) with added titanium. Phys. Rev. 78, 819–820 (1950).

-

Chatterji, T. & Hansen, T. C. Magnetoelastic effects in Jahn–Teller distorted \( CrF_{2} \) and \( CuF_{2} \) studied by neutron powder diffraction. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 23, 276007 (2011).

-

Vecchini, C. et al. Structural distortions in the spin-gap regime of the quantum antiferromagnet \( SrCu_{2}(BO_{3})_{2} \) . J. Solid State Chem. 182, 3275–3281 (2009).

-

Walz, F. The Verwey transition—a topical review. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, R285–R340 (2002).

-

Angst, M. et al. Incommensurate charge order phase in \( Fe_{2}OBO_{3} \) due to geometrical frustration. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 256402 (2007).

-

Frost, D. J. et al. A new large-volume multianvil system. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 143–144, 507–514 (2004).

-

Woodland, A. B., Frost, D. J., Trots, D. M., Klimm, K. & Mezouar, M. In situ observation of the breakdown of magnetite \( \left(\mathrm{Fe}_{3}\mathrm{O}_{4}\right) \) to \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) and hematite at high pressures and temperatures. Am. Mineral. 97, 1808–1811 (2012).

-

Kothapalli, K. et al. Nuclear forward scattering and first-principles studies of the iron oxide phase \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) . Phys. Rev. B 90, 024430 (2014).

-

Woodland, A. B. et al. \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) and its solid solutions in several simple systems. Contrib. Miner. Petrol. 166, 1677–1686 (2013).

-

Ishii, T. et al. High-pressure phase transitions in \( FeCr_{2}O_{4} \) and structure analysis of new post-spinel \( FeCr_{2}O_{4} \) and \( Fe_{2}Cr_{2}O_{3} \) phases with meteoritical and petrological implications. Am. Mineral. 99, 1788–1797 (2014).

-

Guignard, J. & Crichton, W. A. Synthesis and recovery of bulk \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) from magnetite, \( Fe_{3}O_{4} \) . A member of a self-similar series of structures for the lower mantle and transition zone. Mineral. Mag. 78, 361–371 (2014).

-

Verbeeck, J. & Van Aert, S. Model based quantification of EELS spectra. Ultramicroscopy 101, 207–224 (2004).

-

Palatinus, I. & Chapuis, G. SUPERFILP—a computer program for the solution of crystal structures by charge flipping in arbitrary dimensions. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 786–790 (2007).

-

Petricek, V., Dusek, M. & Palatinus, L. Crystallographic computing system JANA2006: general features. Z. Kristallogr. 229, 345–352 (2014).

-

Aksenov, V. L. et al. DN-12 time of flight high pressure neutron spectrometer for investigation of microspamples. Physica B 265, 258–262 (1999).

-

Rodriguez-Carvajal, J. Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Physica B 192, 55–69 (1993).

Acknowledgements

S.V.O. acknowledges the financial support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) under project OV-110/1-3. A.E.K. and V.V.S. acknowledge the support of the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Project 14-02-00622a). H.G. acknowledges the support from the Alexander von Humboldt (AvH) Foundation and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51201148). A.M.A., R.E. and J.V. acknowledge financial support from the European Commission (EC) under the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) under a contract for an Integrated Infrastructure Initiative, Reference No. 312483-ESTEEM2. R.E. acknowledges support from the EC under FP7 Grant No. 246102 IFOX. A.M.A. acknowledges funding from the Russian Science Foundation (Grant No. 14-13-00680). A.A.T. acknowledges funding and from the Federal Ministry for Education and Research through the Sofja Kovalevkaya Award of the AvH Foundation. Funding from the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders under FWO Project G.0044.13N is acknowledged.

M.B. and S.v.S. acknowledge support from the DFG under Project Sm55/15-2. We

acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility for the provision of synchrotron radiation facilities.

Author contributions

S.V.O. synthesized and characterized the \( Fe_{4}O_{5} \) samples. M.B., E.B., S.v.S., V.D. and D.C. performed the single-crystal X-ray diffraction study at low temperatures. M.B. and S.v.S. resolved the structure of the new low-temperature phase. S.E.K. performed the neutron-diffraction measurements. D.P.K. analysed the neutron-diffraction data and derived magnetic-structure models. A.A.T. measured the magnetic properties. A.E.K. and V.V.S. measured the electronic-transport properties. H.G. synthesized the samples and discussed the results. A.M.A., R.E. and J.V. collected and analysed the EELS spectra. D.P.K., A.M.A., A.A.T. and C.M. discussed the magnetic properties and contributed to writing the manuscript. S.V.O. wrote a first draft of the manuscript, and all the co-authors read, revised and commented on it. S.V.O. and L.S.D. initiated and designed the research.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permissions information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to S.V.O.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.