| Transition Temperature | 140 K |

|---|---|

| Experiment Temperature | 10 K |

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | Pm-3m (#221) |

| Magnetic Space Group | R-3m (#166.97) |

| Magnetic Point Group | -3m (20.1.71) |

| Lattice Parameters | 3.90270 3.90270 3.90270 90.00 90.00 90.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b07225 |

| Reference | S. Deng, Y. Sun, L. Wang, Z. Shi, H. Wu, Q. Huang, J. Yan, K. Shi, P. Hu, A. Zaoui, C. Wang, J. Phys. Chem. C (2024) 119 24983 - . |

Article

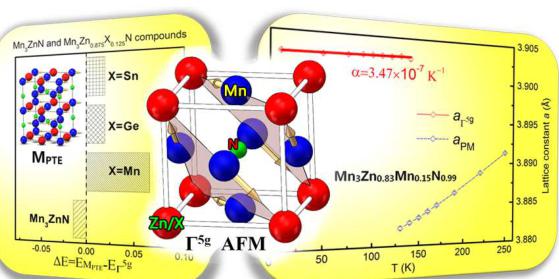

Frustrated Triangular Magnetic Structures of MnZnN: Applications in Thermal Expansion

Sihao Deng, Ying Sun, Lei Wang, Zaixing Shi, Hui Wu, Qing-Zhen Huang, Jun Yan, Kewen Shi, Pengwei Hu, Ali Zaoui, and Cong Wang

J. Phys. Chem. C, Just Accepted Manuscript • DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b07225 • Publication Date (Web): 07 Oct 2015 Downloaded from http://pubs.acs.org on October 13, 2015

Just Accepted

“Just Accepted” manuscripts have been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication. They are posted online prior to technical editing, formatting for publication and author proofing. The American Chemical Society provides “Just Accepted” as a free service to the research community to expedite the dissemination of scientific material as soon as possible after acceptance. “Just Accepted” manuscripts appear in full in PDF format accompanied by an HTML abstract. “Just Accepted” manuscripts have been fully peer reviewed, but should not be considered the official version of record. They are accessible to all readers and citable by the Digital Object Identifier (DOI®). “Just Accepted” is an optional service offered to authors. Therefore, the “Just Accepted” Web site may not include all articles that will be published in the journal. After a manuscript is technically edited and formatted, it will be removed from the “Just Accepted” Web site and published as an ASAP article. Note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the manuscript text and/or graphics which could affect content, and all legal disclaimers and ethical guidelines that apply to the journal pertain. ACS cannot be held responsible for errors or consequences arising from the use of information contained in these “Just Accepted” manuscripts.

Frustrated Triangular Magnetic Structures of \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) :

Applications in Thermal Expansion

Sihao Deng, \( ^{1} \) Ying Sun, \( ^{1,*} \) Lei Wang, \( ^{1} \) Zaixing Shi, \( ^{1} \) Hui Wu, \( ^{2} \) Qingzhen Huang, \( ^{2} \) Jun Yan, \( ^{1} \) Kewen Shi, \( ^{1} \) Pengwei Hu, \( ^{1} \) Ali Zaoui, \( ^{3} \) Cong Wang, \( ^{1,*} \)

\( ^{1} \) Center for Condensed Matter and Materials Physics, Department of Physics, Beihang University, Beijing 100191, People’s Republic of China

\( ^{2} \) NIST Center for Neutron Research, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899-6102, United States

\( ^{3} \) LGCgE-Lille Nord de France, Polytech'Lille, Université de Lille1 Sciences et Technologies,

59655 Villeneuve d'Ascq, France

ABSTRACT:

One of the specific subjects in frustrated magnetic systems is the phenomenon coupled with noncollinear magnetism, such as zero or negative thermal expansion (ZTE or NTE) in antiperovskite compounds. The first-principles calculations and neutron powder diffraction (NPD) are used to reveal the control of the noncollinear \( \Gamma^{5g} \) antiferromagnetic (AFM) structure and corresponding thermal expansion properties in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) (X = Mn, Ge, and Sn). Based on the optimal exchange-correlation functional, our results demonstrate that X (X = Mn, Ge, and Sn) doping at Zn site could stabilize the noncollinear \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM structure and produce magnetovolume effect (MVE). The predictions of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state and MVE is further verified by the NPD results of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N_{0.99} \) . Intriguingly, this special magnetic structure with strong spin-lattice coupling can be tunable to achieve ZTE behavior. On the basis of these results we suggest that frustrated magnetic systems with noncollinear \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM structure of Mn atoms in \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) series of compounds are favorable candidates for a new class of ZTE material.

KEYWORDS: noncollinear magnetism, thermal expansion, spin-lattice coupling, antiperovskite

1. INTRODUCTION

Recent years, frustrated magnetic systems, in which competing interactions between spins preclude simple magnetic orders, have become a stimulating research topic because of the presence of extraordinary magnetic properties such as highly degenerate ground states, novel phase transitions, and noncollinear ordering. \( ^{1-7} \) One of the specific subjects in this field is the phenomenon coupled to noncollinear magnetism. For example, the multiferroic behaviors, caused by an incommensurate cycloidal order combined with spin-orbit coupling, was found in manganite perovskites \( RMnO_{3} \) (such as R = Tb and Dy). \( ^{8, 9} \) Also, colossal magnetoresistance and quantum anomalous Hall effects were observed due to the effect of unusual noncollinear and even noncoplanar spin textures. \( ^{10-12} \) Owing to such diversity of phenomena associated with noncollinear ordering, the exploration in models, materials, and artificial structures related to noncollinear ordering has developed into a very spirited field of investigation. \( ^{10, 13-15} \)

The triangular magnetic lattice is the most obvious example of geometrically frustrated magnetic system. \( ^{[16]} \) Notably, Mn-based antiperovskite compounds with triangular magnetic lattice show a variety of magnetic structures accompanied with fascinating physical properties. A large magnetic entropy change was observed near magnetic transition from paramagnetic (PM) to unusual magnetic state, such as P1 symmetry noncollinear ferrimagnetism (FIM) in \( Mn_{3}Cu_{0.89}N_{0.96} \) and a canted ferromagnetic state in \( Mn_{3}GaC \) . \( ^{[17-19]} \) Giant magnetostriction was reported in the tetragonally distorted ferromagnetic phase of antiperovskite \( Mn_{3}SbN \) and \( Mn_{3}CuN \) . \( ^{[20, 21]} \) Besides, unusual magnetic hysteresis in \( Mn_{3}Sb_{1-x}Sn_{x}N \) and giant magnetoresistance in \( Mn_{3}GaC \) were found. \( ^{[22, 23]} \) More importantly, the antiperovskite compounds with noncollinear \( I^{5g} \) antiferromagnetic (AFM) structure where the Mn local magnetic moments on the (111) plane form clockwise or counterclockwise configuration show attractive behaviors, including giant barocaloric, flexomagnetic, piezomagnetic, Invar-like, and negative thermal expansion (NTE) etc. \( ^{[24-29]} \)

Among these manganese antiperovskites, \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) with \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase, which has the strong spin-lattice coupling, is one of the most promising material as a single compound displaying zero thermal expansion (ZTE) from the perspective of functionality and cost. \( ^{[27, 30]} \) Fruchart et al. reported that \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) was characterized by two distinct magnetic transitions: at 183 K, a high-temperature (high-T) PM state changes to an intermediate-T \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM state with a sudden lattice expansion upon cooling; with further cooling, another magnetic transition from \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM to low-T collinear AFM phases occurs at 140 K, accompanied with a sharp lattice contraction. \( ^{[19, 31]} \) Moreover, from the current neutron powder diffraction (NPD) result of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.99}N \) reported by our group, the coexistence of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM and low-T collinear AFM phases was observed in the intermediate-T region. \( ^{[27]} \) Recently, intermediate-T \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase that controls ZTE and has a larger volume (compared with PM phase) was found to be tunable by chemical substitution at Zn site, such as Ge or Sn. \( ^{[27, 32, 33]} \) On the other hand, reliable methods of the unconstrained noncollinear first-principles study was well established \( ^{[34-36]} \) and widely adopted for explaining and predicting physical properties of materials. \( ^{[25, 34, 37]} \) In this study, the first-principles study based on various exchange-correlation (EC) functionals has been developed in order to get the reasonable ground state of \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) . Based on the preferred EC functional PW91, both \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state and magnetovolume effect (MVE) are confirmed in X doped \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) (X = Ge or Sn), which qualitatively agrees to the experimental results. The prediction that Mn doping at Zn site could induce the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state is verified from our NPD results of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N_{0.99} \) . Additionally, the observed ZTE behavior originated from spin-lattice coupling in \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) series of compounds with \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase provides a new feasible way to obtain ZTE materials.

2. COMPUTATIONAL AND EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

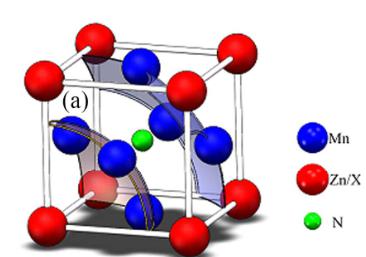

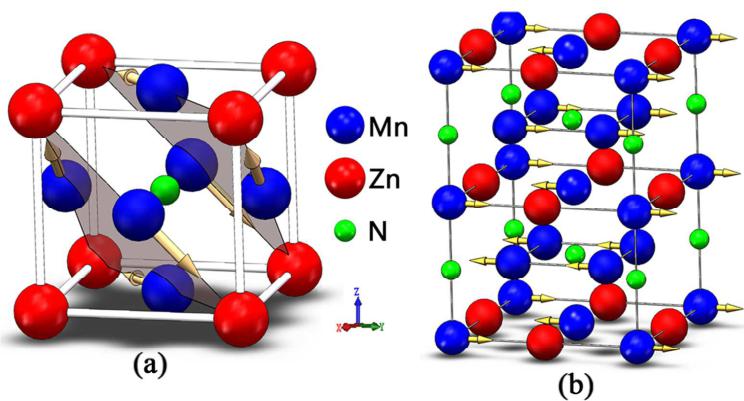

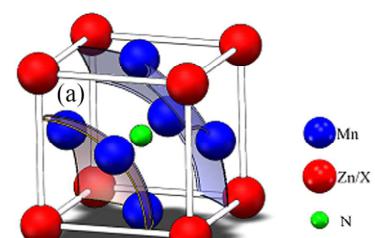

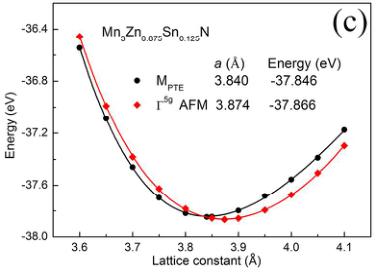

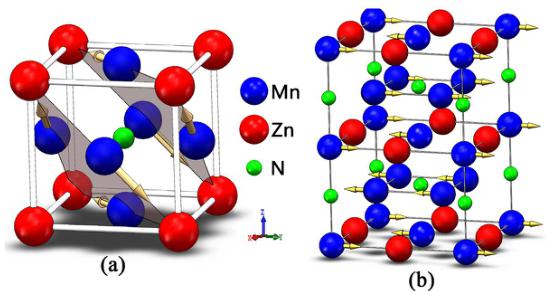

Figure 1. Crystal and magnetic phases of \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) for (a) antiperovskite crystal structure and noncollinear \( I^{5g} \) AFM and (b) collinear AFM structures.

Computational methods

Density functional theory (DFT) was performed here using the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method initially proposed by Blöchl. \( ^{[38]} \) For fully unconstrained noncollinear magnetic structures we used the execution of Kresse and Joubert \( ^{[39]} \) in Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) code within local density approximation (LDA) \( ^{[37]} \) and generalized gradient approximation (GGA) \( ^{[25]} \) . Among the available GGA functionals, we selected two commonly used and popular standard functionals PW91 \( ^{[40]} \) and PBE \( ^{[41]} \) , respectively. Besides, as specially developed functionals for calculations on solids and solid surfaces, AM05 \( ^{[42]} \) and PBEsol \( ^{[43]} \) were also employed. The cutoff energy of 500 eV and Gamma-centered k points with a 3×3×3 grid were used. The noncollinear \( I^{5g} \) magnetic structure with the spins on the (111)-plane was applied. The nonmagnetic supercell with total magnetic moment being zero was adopted to mimic a high-temperature paramagnetic (PM) phase. \( ^{[26]} \) Based on the unit cell of \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) shown in Figure 1(a), a supercell containing 2×2×2 primitive unit cells was adopted. Furthermore, in order to get the composition of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) (X = Mn, Ge, and Sn), the chemical formula \( Mn_{40}Zn_{7}XN_{8} \) supercell was used in our calculations by the substitution of X for Zn.

atom at the site \( (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) \) .

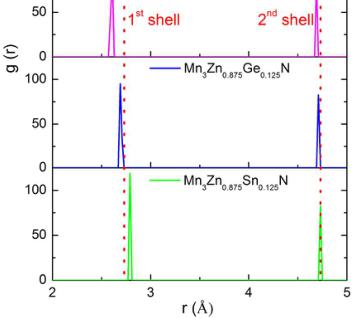

The radial distribution function (RDF), g(r), is very important for studying the structure of \( Mn_{40}Zn_{7}XN_{8} \) . The RDF can be expressed as:

\[ g\left(r\right)=\frac{N_{n}\left(r\right)V_{n}}{4\pi r^{2}drN} \quad (1) \]

where \( N_{n}(r) \) and \( V_{n} \) are the mean numbers and mean volume of atoms between r to \( r+dr \) around an atom, N is the numbers of atoms. \( ^{44} \) For \( Mn_{40}Zn_{7}XN_{8} \) , after optimizing the structure using VASP code, the RDF (Zn/X-Mn around X) is calculated by the VMD software. \( ^{45} \)

Experimental methods

Polycrystalline sample of the nominal composition \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.80}N \) was prepared by solid-state reaction in vacuum ( \( 10^{-5} \) Pa) using \( Mn_{2}N \) and Zn (3N) as the starting materials. \( ^{[27]} \) The real composition determined by Rietveld analysis of NPD data at room temperature is \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N_{0.99} \) . NPD data at 10 K to 250 K were collected using the BT-1 high-resolution neutron powder diffractometer at NIST Center for Neutron Research (NCNR). A Cu (311) monochromator was used to produce monochromatic neutron beam with wavelength of 1.5403 Å. The intensities were measured with a step of \( 0.05^{\circ} \) in the 20 range of \( 5^{\circ}-162^{\circ} \) to determine the crystal and magnetic structures and reveal thermal expansion properties. The crystal and magnetic structures were refined by Rietveld method with the General Structure Analysis System (GSAS) program. \( ^{[46]} \) The neutron scattering lengths used in the refinement were -0.375, 0.568, and \( 0.936 \times 10^{-12} \) cm) for Mn, Zn, and N, respectively. The crystal and magnetic structures of \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) are shown in Figure 1. \( ^{[27]} \)

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As shown in Figure 1(a), \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) possesses an antiperovskite crystal structure. \( ^{[19]} \)

\( ^{27} \) The noncollinear \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM magnetic structure clarified by Fruchart \( ^{[19]} \) [see Figure 1(a)] was adopted for the simulation of \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) . \( ^{[47]} \) Table 1 lists the structural and

magnetic parameters of antiperovskite \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) obtained using different EC functionals with \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM magnetic structure. The calculated equilibrium lattice constants \( a_{0} \) correspond to 3.702, 3.781 and 3.790 Å for the EC functionals LDA, AM05 and PBEsol, respectively, which are underestimated compared with the experimental value of 3.912 Å at 151 K in the literature. \( ^{27} \) Moreover, our calculated \( a_{0} \) value is 3.860 Å for the case of PW91 and 3.871 Å for PBE functional, which is in good agreement with previously reported results, i.e., 3.912 Å. Similarly, the reasonable magnetic moments m of the Mn atoms, 2.60 μB/atom for PBE and 2.51 μB/atom for PW91, are close to the experimental value of 2.61 μB/atom at 151 K. \( ^{27} \) In particular, the values of \( a_{0} \) and m using PBE are close to the previously calculated results 3.870 Å and 2.63 μB/atom. \( ^{47} \) These characteristics with diverse EC functionals indicate that PBE and PW91 are better than others for the current study of \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) .

Table 1. Results of the calculated equilibrium lattice constants \( a_{0} \) and magnetic moment m with different EC functionals compared with experimental data.

| LDA | AM05 | PBEsol | PBE | PW91 | Experiment | |

| \( a_{0} \) ( \( \textup{\AA} \) ) | 3.702 | 3.781 | 3.790 | 3.871, 3.870 \( ^{44} \) | 3.860 | 3.912 \( ^{27} \) |

| m ( \( \mu_{B} \) ) | 2.21 | 2.10 | 2.16 | 2.60, 2.63 \( ^{44} \) | 2.51 | 2.61 \( ^{27} \) |

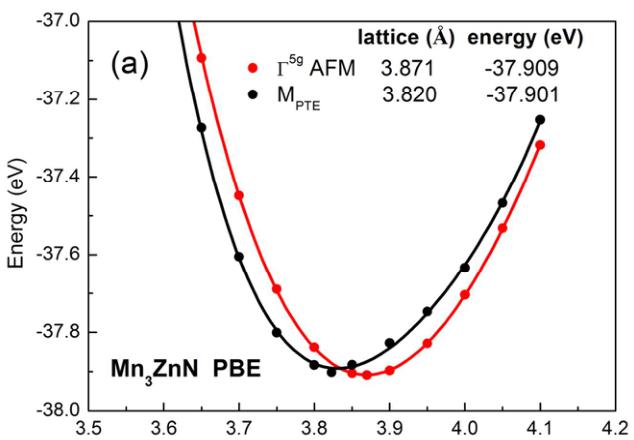

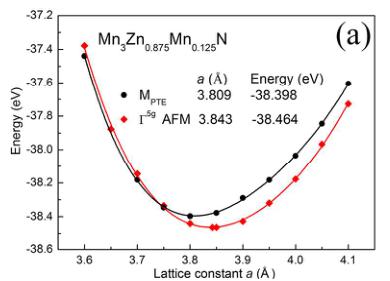

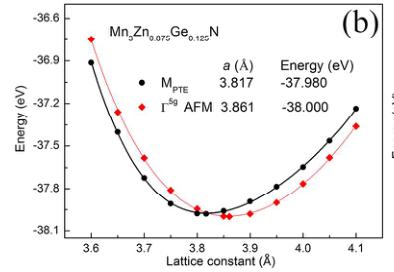

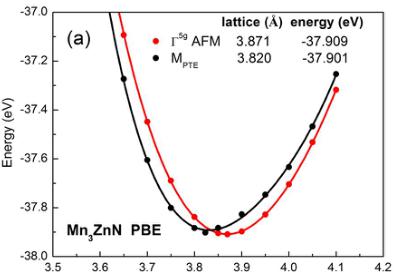

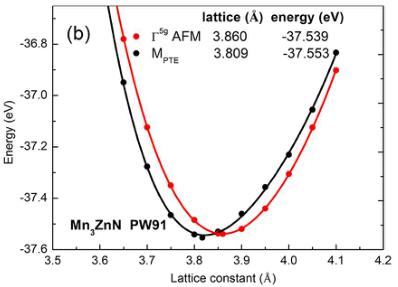

As referred above, \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) shows phase separation behavior [collinear AFM shown in Figure 1(b) and \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phases] from 140 K to 177 K. \( ^{48} \) Herein, the collinear AFM phase is marked as \( M_{PTE} \) in Figure 1(b) as the positive thermal expansion (PTE) behavior was observed within this magnetic structure. \( ^{27} \) Next, we will focus on the discussion of both \( \Gamma^{5g} \) and \( M_{PTE} \) AFM phases using the PBE and PW91 EC functionals. It was found that the cases of PW91 and PBE EC functional show different ground states. The total energy of the \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) as a function of the lattice constant for \( \Gamma^{5g} \) and \( M_{PTE} \) AFM phases are shown in Figure 2. As seen from

Figure 2(a), the total energy of the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) magnetic structure is 0.008 eV/f.u. (f.u. is the abbreviation of formula unit) lower than that of the \( M_{PTE} \) state at their optimal lattices using PBE, which is qualitatively in agreement with the previously calculated results. \( ^{47} \) This indicates that magnetic ground state is \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM structure in the case of PBE EC functional. However, instead of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase, the \( M_{PTE} \) ground state should be observed because this phase was confirmed below 140 K from NPD result. \( ^{27,48} \) Importantly, as shown in Figure 2(b), the \( M_{PTE} \) ground state is obtained in the case of PW91, indicating the PW91 EC functional should be selected for the simulation of \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) .

Figure 2. Total energy of the \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) as a function of the lattice constant for \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM and \( M_{PTE} \) phases using (a) PBE and (b) PW91 EC functionals.

Based on the calculated results by PW91 EC functional, the total energy of the \( M_{PTE} \) 0.014 eV/f.u. is lower than that of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM state at their optimal lattices. Generally, phase separation behavior can be resulted from the thermodynamic competition between phases with nearly identical free energies. \( ^{48, 49} \) For \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) ,

the total energy of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase and that of \( M_{PTE} \) phase is close, and the energy difference 0.014 eV/f.u. is far less than those (similar energy difference) in other antiperovskite compounds (0.463 eV/f.u. for \( Mn_{3.25}Ni_{0.75}N^{26} \) and 0.22 eV/f.u. for \( Mn_{3}GaN^{25} \) ) without phase separation phenomenon. Therefore, the phase separation observed between 140 K and 177 K might be attributed to the competition between \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM and \( M_{PTE} \) phases due to the nearly identical energy of both phases. On the other hand, the equilibrium lattice constant of the \( M_{PTE} \) state is 3.809 Å in the case of PW91, which implies a lattice contraction of 0.051 Å ( \( \Delta a/a = 0.013 \) ) from the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) to \( M_{PTE} \) AFM state. This qualitatively agrees with the observed \( \Gamma^{5g} \rightarrow M_{PTE} \) first-order phase transition in \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) with a \( \Delta a/a \) of \( \sim 0.006 \) . \( ^{27} \) The calculated value of \( \Delta a/a \) is slightly greater than the observed values. However, it does not affect the qualitative analysis of phase transition because such disagreement always exists in the current density functional theory calculation of antiperovskite compounds. \( ^{25, 26} \)

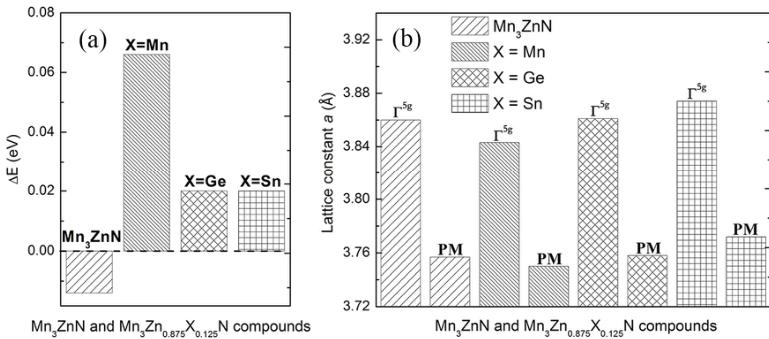

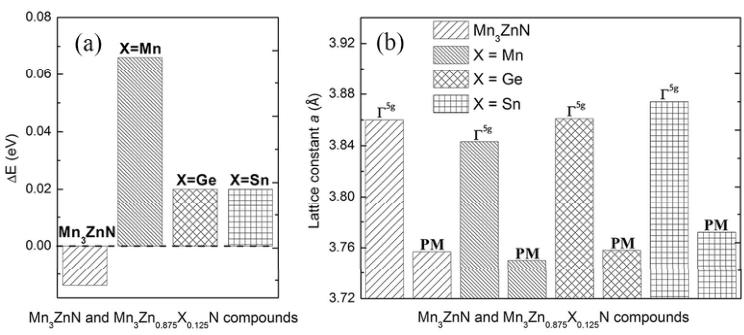

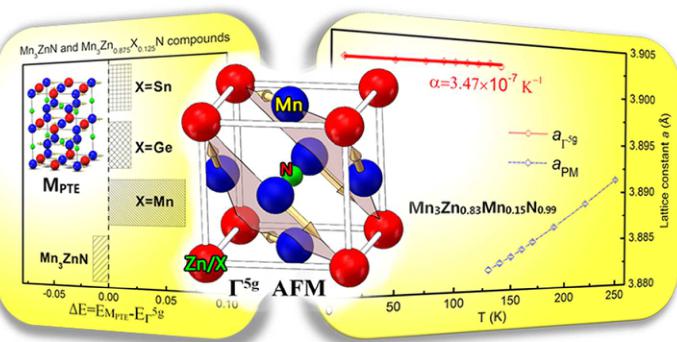

Figure 3. (a) The energy difference \( \Delta E \) between \( E_{M_{PTE}} \) and \( E_{I}^{5g} \) ( \( E_{M_{PTE}}-E_{I}^{5g} \) ) and (b) the equilibrium lattice constant a of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM and PM phases for \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) and \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) (X=Mn, Ge, and Sn) compounds using PW91 EC functional.

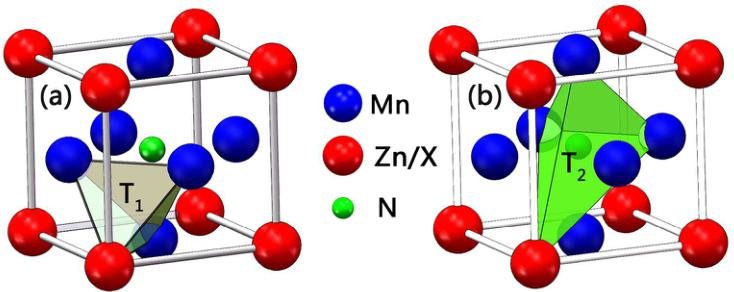

To further study the control of these two magnetic structures, the X doping at Zn site is adopted as \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) \( (X = Mn, Ge, and Sn) \) . Based on the results of total energy at equilibrium lattice displayed in Figure S1, Figure 3(a) shows the

energy difference \( \Delta E \) between \( EM_{PTE} \) and \( E_{1.5^{g}} \) for \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) and \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) (X=Mn, Ge, and Sn) using PW91 EC functional. Negative \( \Delta E \) indicates that the \( M_{PTE} \) AFM phase is favorable; otherwise \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM structure should be stable. It can be seen that the \( \Delta E \) values change from negative to positive with X doping at Zn sites, corresponding to -0.014, 0.066, 0.02, and 0.02 eV for \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) , \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Mn_{0.125}N \) , \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Ge_{0.125}N \) , and \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Sn_{0.125}N \) , respectively. This suggests that X doping could stabilize the special \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase as the ground state in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) . Moreover, as shown in Figure 3(b), the equilibrium lattice constants of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase are 3.861 Å and 3.874 Å for Ge doped and Sn doped compounds, respectively, which are comparable to the experimental values of 3.909 Å for \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.9}Ge_{0.1}N \) at 202 K \( ^{32} \) and 3.930 Å for \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.8}Sn_{0.2}N \) at 265 K \( ^{33} \) . The calculated lattice constants of the PM phase become 3.758 Å for \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Ge_{0.125}N\) and 3.772 Å for \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Sn_{0.125}N\) , signifying that the lattice contraction ( \( \Delta a/a \) ) 0.027 for Ge doping and 0.026 for Sn doping could be observed with magnetic transition from \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM to PM phase. These characteristics qualitatively agree with the experimental results, e.g., antiperovskite compounds \( Mn_{3}Zn_{1-x}X_{x}N \) with X (X = Ge and Sn) doping have been found to contain \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state and exhibit NTE (ZTE) behavior that caused by MVE effect. \( ^{27, 32, 33} \) This suggests that we could make a prediction on the antiperovskite compounds with \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state using PW91 EC functional. On the other hand, for Mn doped \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Mn_{0.125}N\) , the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state and MVE effect are also predicted, which will be discussed in the following experimental section.

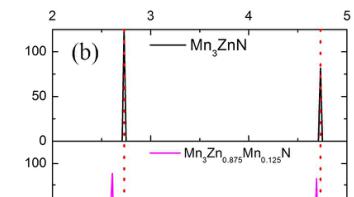

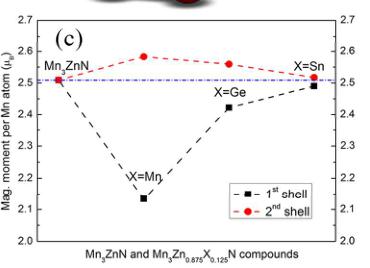

Figure 4. (a) Crystal structure showing the first \( (1^{\mathrm{st}}) \) and second \( (2^{\mathrm{nd}}) \) nearest shells (Zn/X-Mn) around X atom for \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) and \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) (X= Mn, Ge, and Sn). (b) Corresponding radial distribution function and (c) magnetic moment per Mn atom for \( 1^{st} \) and \( 2^{nd} \) shells.

The \( M_{PTE}-\Gamma^{5g} \) AFM (collinear-noncollinear) phase transition induced by X doping at Zn positions inspires us to explore the influence of doping on the structural changes in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) (X = Mn, Ge, and Sn) because the magnetic phase transitions led by degenerating spin states around the ground state might be found due to the local lattice distortion. \( ^{16, 50} \) The RDF of the first ( \( 1^{st} \) ) and the second ( \( 2^{nd} \) ) nearest shells (Zn-Mn, Mn-Mn, Ge-Mn, and Sn-Mn) around X atom for \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) and $ Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N(X=Mn,Ge,andSn)are shown in Figure 4(b). For the \( 1^{st} \) shell, the peaks are weakened and the shift of peak position occurs with X doping in \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) . These characteristics indicate that the geometrical distortion could be produced by X doping at Zn sites. However, only the tiny change is found with X doping for the \( 2^{nd} \) shell, implying that the geometrical distortion induced by doping could mainly locate near the doped site. On the other hand, the magnetic moment per Mn atom for the \( 1^{st} \) and \( 2^{nd} \) shell is shown in Figure 4(c). It can be seen that the X doping has more

influence on Mn magnetic moment in the 1 \( ^{st} \) shell compared with those in the 2 \( ^{nd} \) shell. For the 1 \( ^{st} \) shell, the values of Mn magnetic moment \( m_{Mn} \) are 2.13, 2.42 and 2.49 \( \mu_{B}/Mn \) for X = Mn, Ge, and Sn, respectively, smaller than 2.51 \( \mu_{B}/Mn \) in \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) . However, slightly larger values of 2.58, 2.56, and 2.52 \( \mu_{B}/Mn \) are observed for \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Mn_{0.125}N \) , \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Ge_{0.125}N \) , and \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Sn_{0.125}N \) , respectively, in the 2 \( ^{nd} \) shell. Notably, in antiperovskite compounds, the spin-lattice coupling of the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase was confirmed by NPD results. \( ^{26, 27} \) Moreover, a decrease in the Mn magnetic moment (unpaired Mn 3d electrons) was found with Ge doping due to Ge 4p - Mn 3d orbital hybridization. \( ^{51} \) For the compounds with Mn doping, the contraction (relative expansion) of the 1 \( ^{st} \) (2 \( ^{nd} \) ) shell caused by geometrical distortion may be coupled to Mn magnetic moment, resulting in the decrease (increase) of \( m_{Mn} \) . For \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Ge_{0.125}N and Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Sn_{0.125}N \) , the tiny variation of \( m_{Mn} \) in the 2 \( ^{nd} \) shell is observed with insignificant geometrical distortion, while the deceasing \( m_{Mn} \) in the 1 \( ^{st} \) shell might be produced by the contribution from p-d (Ge 4p - Mn 3d, Sn 5p - Mn 3d) orbital hybridization and the spin-lattice coupling. However, details of these complicated contributions still need further investigations. Furthermore, combined with the discussions of the magnetic moment changes induced by X doping, some detailed analyses for the geometrical distortion of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) are shown in the Support Information.

The \( M_{PTE}-I^{5g} \) AFM phase transition with X doping will be studied based on local lattice distortion. Firstly, we will focus on the nature of \( M_{PTE} \) in \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) . Generally, the simply collinear antiferromagnetic ordering is impossible in a two-dimensional triangular lattice. \( ^{52} \) We suggest that the \( M_{PTE} \) , which AFM lays are perpendicular to c axis, might be formed by the effect of the anisotropy energy in \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) . Similarly, as a typical material of triangular lattice antiferromagnet, \( CuFeO_{2} \) forms an Ising-like 4-sublattice ( \( \uparrow\uparrow\downarrow\downarrow \) ) collinear AFM ordering due to the effect of the anisotropy energy when the easy-axis anisotropy is sufficiently large. \( ^{1,7,10,16,52,53} \) Noticeably, these collinear AFM orderings are contrary to the typical noncollinear ordered structure of

triangular lattice antiferromagnet where the three spins align at \( 120^{\circ} \) from each other in the basal plane, such as the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase in \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) .¹,⁵⁴ Moreover, the spin-wave softening may be found as the collinear-noncollinear magnetic phase transition occurs in triangular lattice antiferromagnet. For the typical material \( CuFeO_{2} \) , the Spin-wave gap is observed to decrease by substituting \( Al^{3+} \) ions for \( Fe^{3+} \) . When the Al concentration is greater than 1.6%, the collinear AFM phase becomes unstable and a noncollinear phase appears.⁵²,⁵⁵,⁵⁶. Additionally, it is clear that the local lattice distortion caused by the difference of ionic radii between the doped element (e.g. \( Al^{3+} \) ) and \( Fe^{3+} \) significantly affects the spin states in \( CuFe_{1-x}Ga_{x}O_{2} \) .⁵⁰ Therefore, it is proposed that, for geometrically frustrated \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) , a similar spin-wave softening accompanied by local lattice distortion might be observed due to X doping, which could lead to the collinear-noncollinear magnetic phase transition.

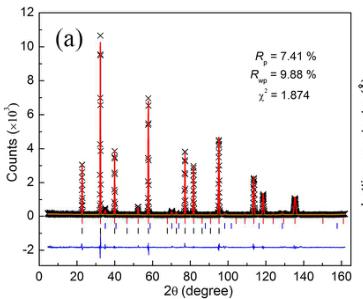

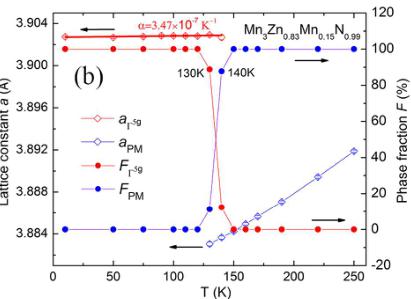

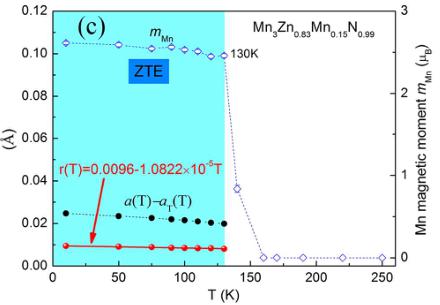

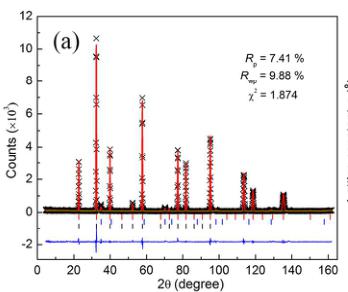

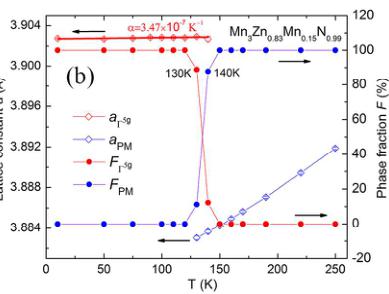

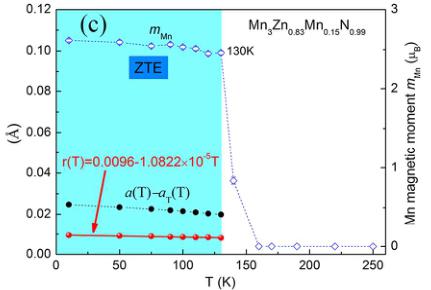

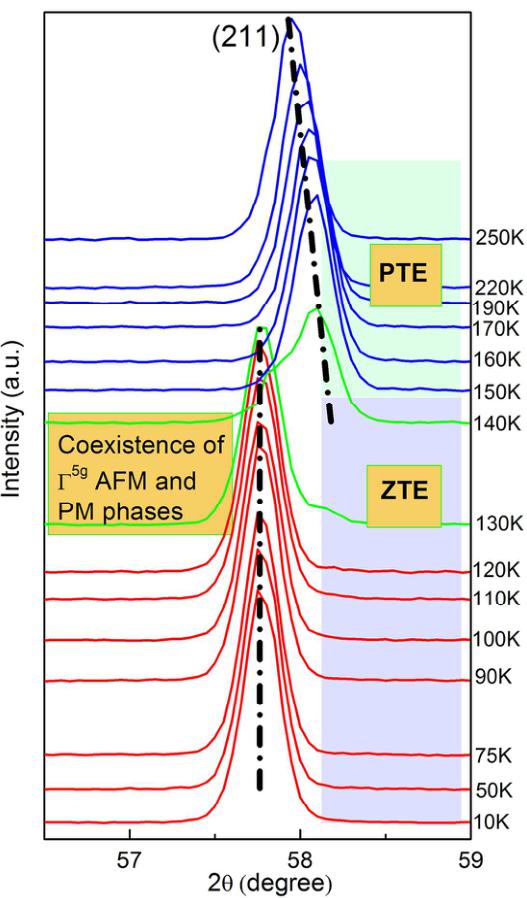

Figure 5. (a) Neutron powder diffraction patterns of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N_{0.99} \) at 10 K. The crosses

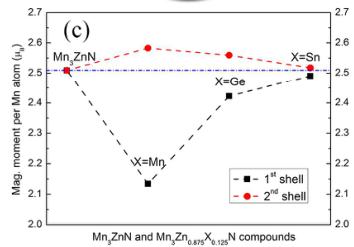

show the experimental intensities \( (I_{\mathrm{obs}}) \) , the upper solid line shows the calculated intensities \( (I_{\mathrm{calc}}) \) , and the lower solid line is the difference between the observed and calculated intensities \( (I_{\mathrm{obs}}-I_{\mathrm{calc}}) \) . The vertical lines indicate the angular positions of the nuclear (top row), MnO (second row), and the magnetic (third row) Bragg reflections. (b) Relationship between the lattice variation and phase fractions for the sample \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N_{0.99} \) . Solid symbols represent phase fractions and open symbols depict lattice constants. Curves are guides to the eye. (c) Temperature dependence of the lattice variation \( a(\mathrm{T})-a_{\mathrm{T}}(\mathrm{T}) \) , ordered magnetic moments \( (m_{\mathrm{Mn}}) \) of the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM structure, and \( \mathrm{r}(\mathrm{T}) \) for \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N_{\mathrm{0.99}} \) .

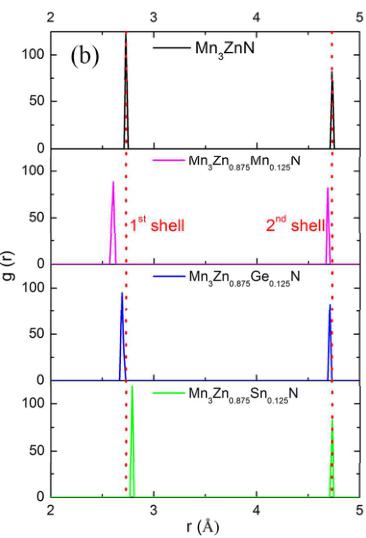

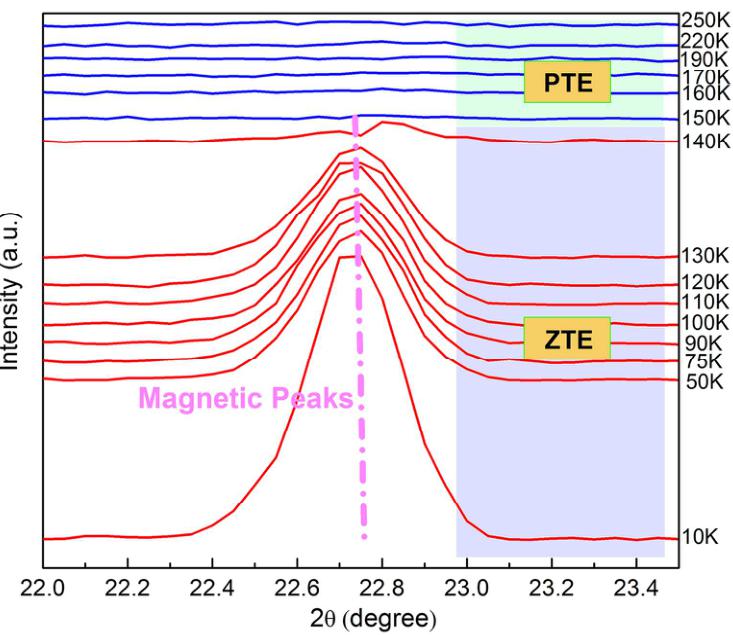

In order to verify the prediction that Mn doping at Zn site could induce the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state, the sample with refined compositions of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N0.99 \) was synthesized and analyzed by NPD method. Figure 5(a) shows the NPD pattern of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}Ni_{0.99} \) at 10 K. The NPD pattern could be fitted well with a structural model of cubic symmetry and the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM model, as shown in Figure 1(a). For \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) , it has been investigated previously, with a \( M_{PTE} \) magnetic ground state and a combination of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) and \( M_{PTE} \) AFM phases between 140 K and 177 K. Noticeably, our NPD study indicates that the ground state phase becomes \( \Gamma^{5g} \) symmetry in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N^{0.99} \) , suggesting that we could stabilize the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase by Mn doping at Zn site. Moreover, the refined lattice constant a and AFM moment of Mn are 3.90274 Å and 2.60 \( \mu_{B}/Mn \) , respectively, in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}Ni^{0.99} \) , which are less than the values 3.912 Å and 2.61 \( \mu_{B}/Mn \) in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.99}N^{0.27} \) . This is in qualitative agreement with the calculated results that Mn doping could induce the decreasing of a and \( m_{Mn} \) in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}Mn_{0.125}N \) . On the other hand, the evolution of lattice constant and phase fractions with temperature is taken into consideration, as shown in Figure 5(b). Table S1 gives more details for the refined structural parameters of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}M^{0.99} \) compound at some representative temperature. For the phase fractions, the transition from \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM to PM is incomplete, and the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) phase fraction decreases gradually upon further heating and coexists with the PM phase between 130

and 140 K. Figure S3 provides supplementary details about the evolution of the NPD pattern with temperature. In addition, the MVE effect with magnetic transition from \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM (large volume) to PM (small volume) phases is observed as the previously calculated prediction. More importantly, the ZTE behavior is observed below 140 K within \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase, corresponding to the coefficient of linear thermal expansion \( \alpha_{l} = 3.47 \times 10^{-7} \) K \( ^{-1} \) . This demonstrates that the ZTE behavior can be obtained by achieving the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase in antiperovskite compounds. \( ^{26,27} \)

Figure 5(c) gives the temperature dependence of the ordered magnetic moments \( (m_{\mathrm{Mn}}) \) of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM structure. The abrupt contraction in the volume is observed when \( m_{Mn} \) suddenly drops rapidly. This indicates a close correlation between the anomalous volume variation and the magnetic ordering, confirming the lattice is coupled to the Mn magnetic ordering. \( ^{26} \) Additionally, more details for the correlation between thermal expansion behaviors and intensities of the magnetic peak are shown in Figure S4 in the Supporting Information. In order to further investigate the spin-lattice coupling in the \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase, we assume that \( \alpha_{\mathrm{T}}(\mathrm{T}) = \alpha_{\mathrm{PTE}}(\mathrm{T}) \) where \( \alpha_{\mathrm{T}}(\mathrm{T}) \) and \( \alpha_{\mathrm{PTE}}(\mathrm{T}) \) are defined as the coefficient of the usual thermal expansion contributed by the lattice vibration in the ZTE (blow 140 K) and PTE region (above 140 K), respectively. And the lattice constant \( a_{\mathrm{T}}(\mathrm{T}) \) can be obtained from the fitting curve of PTE constants above 140 K using the cubic function (shown in the equation (1) of Supporting Information). \( ^{26,27} \) Indicating \( a(\mathrm{T}) \) as the observed lattice constant, we take the difference \( \Delta a_{\mathrm{m}}(\mathrm{T}) = a(\mathrm{T}) - a_{\mathrm{T}}(\mathrm{T}) \) to isolate the effect of the NTE. As shown in the Figure 5(c), it can be seen that \( \Delta a_{\mathrm{m}}(\mathrm{T}) \) of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N_{0.99} \) at ZTE region decreases modestly with increasing temperature, but approximately at the same rate as the ordered moment decreasing. Therefore we define a ratio \( \mathrm{r}(\mathrm{T}) = \Delta a_{\mathrm{m}}(\mathrm{T}) / m_{\mathrm{Mn}}(\mathrm{T}) \) as the extent of the NTE effect connected with the magnitude of the ordered moment \( m_{\mathrm{Mn}}(\mathrm{T}) \) . For \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N{}_{0.99} \) , the ratio \( \mathrm{r}(\mathrm{T}) \) , which is found to be a linear function with an extremely low coefficient value of \( -1.0822 \times 10^{-5} \) , is approximately independent of T at the ZTE region. This reveals a strong spin-lattice coupling.

phenomenon for \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N_{0.99} \) , which has also been confirmed in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{x}N \) , \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.41}Ag_{0.41}N \) and \( Mn_{3+x}Ni_{1-x}N \) antiperovskite compounds with \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM phase. \( ^{26,27} \) This spin-lattice coupling could balance the contribution of the lattice vibration, and then produce ZTE behavior.

4. CONCLUSION

In summary, we have theoretically demonstrated that X doping at Zn site in \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) (X = Mn, Ge, and Sn) could stabilize the noncollinear \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM structure, and experimentally verify the prediction of \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state (with Mn doping) that can be tunable to achieve ZTE behavior. Our calculated results with diverse EC functionals indicate that PW91 is the best one compared with others for the current study of \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) . Moreover, \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state and NTE behavior that caused by MVE effect are confirmed in X (X = Ge, Sn, and Mn) doped \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.875}X_{0.125}N \) . The reasons for collinear-noncollinear magnetic phase transition induced by doping are discussed based on local lattice distortion. In addition, from the NPD results of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{0.83}Mn_{0.15}N^{0.99} \) , the predicted \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state and the ZTE caused by strong spin-lattice coupling are observed. The present study suggests that frustrated triangular magnetic systems with noncollinear \( \Gamma^{5g} \) AFM ground state are promising candidates for ZTE material with strong spin-lattice coupling in antiperovskite compounds.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The total energies as a function of the lattice constant, some detailed analyses for the geometrical distortion, NPD patterns, cubic function of fitting curve, and refined structural parameters. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the

ACS Publications website.

AUTHOR INFORMATION

Corresponding Authors

\( ^{*} \) E-mail: sunying@buaa.edu.cn.

\( ^{*} \) E-mail: congwang@buaa.edu.cn.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Nos. 51172012 and 51472017), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and State Key Lab of Advanced Metals and Materials (2014-ZD03). The authors also acknowledge the support of Foundation of Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Z141109004414063).

■ REFERENCES

\( ^{1} \) Ye, F.; Fernandez-Baca, J. A.; Fishman, R. S.; Ren, Y.; Kang, H. J.; Qiu, Y.; Kimura, T. Magnetic Interactions in the Geometrically Frustrated Triangular Lattice Antiferromagnet \( CuFeO_{2} \) . Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 157201.

\( ^{2} \) Ramirez, A. P.; Hayashi, A.; Cava, R. J.; Siddharthan, R.; Shastry, B. S. Zero-Point Entropy in ‘Spin Ice’. Nature (London) 1999, 399, 333-335.

\( ^{3} \) Kimura, T.; Goto, T.; Shintani, H.; Ishizaka, K.; Arima, T.; Tokura, Y. Magnetic Control of Ferroelectric Polarization. Nature (London) 2003, 426, 55-58.

\( ^{4} \) Hur, N.; Park, S.; Sharma, P. A.; Ahn, J. S.; Guha, S.; Cheong, S-W. Electric

Polarization Reversal and Memory in a Multiferroic Material Induced by Magnetic Fields. Nature (London) 2004, 429, 392-395.

\( ^{5} \) Lottermoser, T.; Lonkai, T.; Amann, U.; Hohlwein, D.; Ihringer, J.; Fiebig, M. Magnetic Phase Control by an Electric Field. Nature (London) 2004, 430, 541-544.

\( ^{6} \) Diep, H. T. Frustrated Spin Systems. World Scientific: Singapore, 2005.

\( ^{7} \) Melchy, P. -É.; Zhitomirsky, M. E. Interplay of Anisotropy and Frustration: Triple Transitions in a Triangular-Lattice Antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 064411.

\( ^{8} \) Landsgesell, S.; Prokeš, K.; Ouladdiaf, B.; Klemke, B.; Prokhnenko, O.; Hepp, B.; Kiefer, K.; Argyriou, D. N. Magnetoelectric Properties in Orthorhombic \( Nd_{1-x}Y_{x}MnO_{3} \) : Neutron Diffraction Experiments. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 054429.

\( ^{9} \) Cheong, S.-W.; Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: a Magnetic Twist for Ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 13-20.

\( ^{10} \) Reja, S.; Ray, R.; Brink, J.; Kumar, S. Coupled Spin-Charge Order in Frustrated Itinerant Triangular Magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 140403(R).

\( ^{11} \) Salamon, M.; Jaime, M. The Physics of Manganites: Structure and Transport. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 583-628.

\( ^{12} \) Nagaosa, N.; Sinova, J.; Onoda, S.; MacDonald, A. H.; Ong, N. P. Anomalous Hall Effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 1539-1592.

\( ^{13} \) Wang, R. F.; Nisoli, C.; Freitas, R. S.; Li, J.; McConville, W.; Cooley, B. J.; Lund, M. S.; Samarth, N.; Leighton, C.; Crespi, V. H.; Schiffer, P. Artificial ‘Spin Ice’ in a Geometrically Frustrated Lattice of Nanoscale Ferromagnetic Islands. Nature (London) 2006, 439, 303-306.

\( ^{14} \) Nisoli, C.; Moessner, R.; Schiffer, P. Colloquium: Artificial Spin Ice: Designing and Imaging Magnetic Frustration. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013, 85, 1473-1490.

\( ^{15} \) Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Multiple-Q Instability by (d-2)-Dimensional Connections of Fermi Surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 060402.

\( ^{16} \) Kimura, T.; Lashley, J. C.; Ramirez, A. P. Inversion-Symmetry Breaking in the Noncollinear Magnetic Phase of the Triangular-Lattice Antiferromagnet \( CuFeO_{2} \) . Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 220401(R).

\( ^{17} \) Yu, M. H.; Lewis, L. H.; Moodenbaugh, A. R. Large Magnetic Entropy Change in

the Metallic Antiperovskite \( Mn_{3}GaC \) . J Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 10128-10130.

\( ^{18} \) Yan, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, H.; Huang, Q. Z.; Wang, C.; Shi, Z. X.; Deng, S. H.; Shi, K. W.; Lu, H. Q.; Chu, L. H. Phase Transitions and Magnetocaloric Effect in \( Mn_{3}Cu_{0.89}N_{0.96} \) . Acta Mater. 2014, 74, 58-65.

\( ^{19} \) Fruchart, D.; Bertaut, E. F. Magnetic Studies of the Metallic Perovskite-Type Compounds of Manganese. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1978, 44, 781-791.

\( ^{20} \) Shimizu, T.; Shibayama, T.; Asano, K.; Takenaka, K. Giant Magnetostriction in Tetragonally Distorted Antiperovskite Manganese Nitrides. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 07A903.

\( ^{21} \) Shibayama, T.; Takenaka, K. Giant Magnetostriction in Antiperovskite \( Mn_{3}CuN \) . J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 07A928.

\( ^{22} \) Sun, Y.; Guo, Y. F.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Feng, H. L.; Sathish, C. I.; Matsushita, Y.; Yamaura, K. Unusual Magnetic Hysteresis and the Weakened Transition Behavior Induced by Sn Substitution in \( Mn_{3}SbN \) . J. Appl. Lett. 2014, 115, 043509.

\( ^{23} \) Kamishima, K.; Goto, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Miura, N.; Ohashi, M.; Mori, N. Giant Magnetoresistance in the Intermetallic Compound \( Mn_{3}GaC \) . Phys. Rev. B 2000, 63, 024426.

\( ^{24} \) Matsunami, D.; Fujita, A.; Takenaka, K.; Kano, M. Giant Barocaloric Effect Enhanced by the Frustration of the Antiferromagnetic Phase in \( Mn_{3}GaN \) . Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 73-78.

\( ^{25} \) Lukashev, P.; Sabirianov, R. F.; Belashchenko, K. Theory of the Piezomagnetic Effect in Mn-based Antiperovskites. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 184414.

\( ^{26} \) Deng, S. H.; Sun, Y.; Wu, H.; Huang, Q. Z.; Yan, J.; Shi, K. W.; Malik, M. I.; Lu, H. Q.; Wang, L.; Huang, R. J.; Li, L. F.; Wang, C. Invar-like Behavior of Antiperovskite \( Mn_{3+x}Ni_{1-x}N \) Compounds. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 2495-2501.

\( ^{27} \) Wang, C.; Chu, L. H.; Yao, Q. R.; Sun, Y.; Wu, M. M.; Ding, L.; Yan, J.; Na, Y. Y.; Tang, W. H.; Li, G. N.; Huang, Q. Z.; Lynn, J. W. Tuning the Range, Magnitude, and Sign of the Thermal Expansion in Intermetallic \( \mathrm{Mn}_{3}(\mathrm{Zn}, \mathrm{M})_{x}\mathrm{N} \) (M = Ag, Ge). Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 220103(R).

\( ^{28} \) Iikubo, S.; Kodama, K.; Takenaka, K.; Takagi, H.; Takigawa, M.; Shamoto, S. Local Lattice Distortion in the Giant Negative Thermal Expansion Material

\( Mn_{3}Cu_{1-x}Ge_{x}N \) . Phys. Rev. Lett 2008, 101, 205901.

\( ^{29} \) Song, X. Y.; Sun, Z. H.; Huang, Q. Z.; Rettenmayr, M.; Liu, X. M.; Seyring, M.; Li, G. N.; Rao, G. H.; Yin, F. X. Adjustable Zero Thermal Expansion in Antiperovskite Manganese Nitride. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4690-4694.

\( ^{30} \) Hamada, T.; Takenaka, K. Phase Instability of Magnetic Ground State in Antiperovskite \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) : Giant Magnetovolume Effects Related to Magnetic Structure. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 07A904.

\( ^{31} \) Fruchart, R.; Madar, R.; Barberon, M.; Fruchart, E.; Lorthioir, M. G. Transitions Magnétiques et Déformations Cristallographiques Associées Dans les Nitrures du Type Perowskite \( ZnMn_{3}N \) et \( SnMn_{3}N \) . J. Phys. (Paris) 1971, 32, 982-984.

\( ^{32} \) Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Wen, Y. C.; Zhu, K. G.; Zhao J. T. Lattice Contraction and Magnetic and Electronic Transport Properties of \( Mn_{3}Zn_{1-x}Ge_{x}N \) . Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 231913.

\( ^{33} \) Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Wen, Y. C.; Chu, L. H.; Pan, H.; Nie, M. Negative Thermal Expansion and Magnetic Transition in Anti-Perovskite Structured \( Mn_{3}Zn_{1-x}Sn_{x}N \) Compounds. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 93, 2178-2181.

\( ^{34} \) Ma, P. W.; Dudarev, S. L. Constrained Density Functional for Noncollinear Magnetism. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 054420.

\( ^{35} \) Mryasov, O. N.; Gubanov, V. A.; Liechtenstein, A. I. Spiral-Spin-Density-Wave States in Fcc Iron: Linear-Muffin-Tin-Orbitals Band-Structure Approach. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 12330.

\( ^{36} \) Mryasov, O. N.; Lichtenstein, A. I.; Sandratskii, L. M.; Gubanov, V. A. Magnetic Structure of FCC Iron. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1991, 3, 7683-7690.

\( ^{37} \) Lukashev, P.; Belashchenko, K. D.; Sabirianov, R. F. Large Magnetoelectric Effect in Ferroelectric/Piezomagnetic Heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 134420.

\( ^{38} \) Blöchl, P. Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B, 1994, 50, 17953-17979.

\( ^{39} \) Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From Ultrasoft Pseudopotentials to the Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758-1775.

\( ^{40} \) Perdew, J. P.; Wang, Y. Accurate and Simple Analytic Representation of the Electron-Gas Correlation Energy. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 13244-13249.

\( ^{41} \) Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865-3868.

\( ^{42} \) Mattsson, A. E.; Armiento, R.; Paier, J.; Kresse, G.; Wills, J. M.; Mattsson, T. R. The AM05 Density Functional Applied to Solids. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 084714.

\( ^{43} \) Ropo, M.; Kokko, K.; Vitos, L. Assessing the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof Exchange-Correlation Density Functional Revised for Metallic Bulk and Surface Systems. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 195445.

\( ^{44} \) Liu, C. M.; Chen, X. R.; Xu, C.; Cai, L. C.; Jing, F. Q. Melting Curves and Entropy of Fusion of Body-Centered Cubic Tungsten Under Pressure. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 013518.

\( ^{45} \) Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD - Visual Molecular Dynamics, J. Molec. Graphics 1996, 14, 33-38.

\( ^{46} \) Larson, A. C.; Von Dreele, R. B. General Structure Analysis System (GSAS), Technical Report LAUR 86-748 for Los Alamos National Laboratory: Los Alamos, NM, 2004.

\( ^{47} \) Qu, B. Y.; Pan, B. C. Nature of the Negative Thermal Expansion in Antiperovskite Compound \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) . J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 108, 113920.

\( ^{48} \) Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, Q. Z.; Guo, Y. F.; Chu, L. H.; Arai, M. S.; Yamaura, K. Neutron Diffraction Study of Unusual Phase Separation in the Antiperovskite Nitride \( Mn_{3}ZnN \) . Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 7232-7236.

\( ^{49} \) Granado, E.; Huang, Q.; Lynn, J. W.; Gopalakrishnan, J.; Greene, R. L.; Ramesha, K. Spin-Orbital Ordering and Mesoscopic Phase Separation in the Double Perovskite \( Ca_{2}FeReO_{6} \) . Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 064409.

\( ^{50} \) Terada, N.; Nakajima, T.; Mitsuda, S.; Kitazawa, H.; Kaneko, K.; Metoki, N. Ga-Substitution-Induced Single Ferroelectric Phase in Multiferroic \( CuFeO_{2} \) . Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 014101.

\( ^{51} \) Hua, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, L. F. First-Principles Investigation of Ge Doping Effects on the Structural, Electronic and Magnetic Properties in Antiperovskite \( Mn_{3}CuN \) . J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 206003.

\( ^{52} \) Fishman, R. S.; Okamoto, S. Noncollinear Magnetic Phases of a Triangular-Lattice Antiferromagnet and of Doped \( CuFeO_{2} \) . Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 020402(R).

\( ^{53} \) Wang, F.; Vishwanath, A. Spin Phonon Induced Collinear Order and Magnetization Plateaus in Triangular and Kagome Antiferromagnets: Applications to \( CuFeO_{2} \) . Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 077201.

\( ^{54} \) Kawamura, H. Universality of Phase Transitions of Frustrated Antiferromagnets. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1998, 10, 4707-4754.

\( ^{55} \) Fishman, R. S. Spin Waves in \( CuFeO_{2} \) . J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 07B109.

\( ^{56} \) Seki, S.; Yamasaki, Y.; Shiomi, Y.; Iguchi, S.; Onose, Y.; Tokura, Y. Intrinsic Damping of Spin Waves by Spin Current in Conducting Two-Dimensional Systems. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 75, 100403(R).

Table of Contents

| LDA | AM05 | PBEsol | PBE | PW91 | Experiment | |

| \( a_{0} \) ( \( \textup{\AA} \) ) | 3.702 | 3.781 | 3.790 | 3.871, 3.870 \( ^{44} \) | 3.860 | 3.912 \( ^{27} \) |

| \( m \) ( \( \mu_{B} \) ) | 2.21 | 2.10 | 2.16 | 2.60, 2.63 \( ^{44} \) | 2.51 | 2.61 \( ^{27} \) |

Table 1 for manuscript 108x35mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Figure 1 for manuscript 102x56mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Figure 2 for manuscript 75x105mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Figure 3 for manuscript 150x66mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Figure 4 for manuscript 146x104mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Figure 5 for manuscript 150x117mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Figure S1 for Supporting information 172x125mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Figure S2 for Supporting information 141x57mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Figure S3 for Supporting information 96x147mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Figure S4 for Supporting information 134x117mm (300 x 300 DPI)

| T (K) | a | Ert a | mMn | Ert mMn | R (%) | Rvp (%) | \( \chi^{2} \) (%) | Uiso (Mn) | Uiso (Zn) | Uiso (N) | |

| 10 | 3.90274 | 8×10-5 | 2.60 | 0.02 | 7.41 | 9.88 | 1.874 | 3.01×10-3 | 3.50×10-3 | 1.40×10-3 | |

| 11 | 3.90284 | 9×10-5 | 2.51 | 0.02 | 6.78 | 8.76 | 1.265 | 3.60×10-3 | 3.79×10-3 | 2.30×10-3 | |

| 12 | 3.8856 | 1×10-4 | 0 | - | 7.86 | 8.81 | 1.543 | 5.16×10-3 | 5.21×10-3 | 2.84×10-3 | |

| 13 | 3.8919 | 1×10-4 | 0 | - | 6.26 | 7.31 | 1.342 | 5.25×10-3 | 6.54×10-3 | 3.94×10-3 | |

| 14 | 3.8919 | 1×10-4 | 0 | -<fcel> | 6.26 | 7.31 | 1.342 | 5.2 | 6.54×10-3 | 3.94×10-3 |

Table S1 for Supporting information 109x38mm (300 x 300 DPI)

Table of Contents for manuscript 74x35mm (300 x 300 DPI)