| Transition Temperature | 30 K |

|---|---|

| Experiment Temperature | 4.5 K |

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | R-3c (#167) |

| Magnetic Space Group | C2/c (#15.85) |

| Magnetic Point Group | 2/m (5.1.12) |

| Lattice Parameters | 4.60900 4.60900 14.73700 90.00 90.00 120.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1103/physrevb.28.4016 |

| Reference | R. Plumier, M. Sougi and R. Saint-James, Physical Review B (1983) 28 4016-4020. |

| Label | Element | Mx | My | Mz | |M| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni1 | Ni | 1. | 2. | 0.0 | 1.73 |

Brief Reports are short papers which report on completed research or are addenda to papers previously published in the Physical Review. A Brief Report may be no longer than 3½ printed pages and must be accompanied by an abstract.

Neutron-diffraction reinvestigation of \( NiCO_{3} \)

R. Plumier, M. Sougi, and R. Saint-James

Institut de Recherche Fondamentale, Département de Physique Générale, Service de Physique

du Solide et de Résonance Magnétique,

Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique, Centre d'Etudes Nucléaires de Saclay,

F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette Cedex, France

(Received 29 March 1983)

Detailed powder neutron-diffraction experiments performed on \( NiCO_{3} \) show that at low temperature this carbonate is an antiferromagnet with an antiferromagnetic direction perpendicular to the trigonal axis and not at an angle \( 63^{\circ} \) to this axis as has been previously reported. The oxygen parameter is found to be \( u=0.2813\pm0.0005 \) , the largest found in the series of carbonates of the iron family. A careful examination of the magnetic reflection intensities indicates in \( NiCO_{3} \) a form-factor expansion and a magnetic-moment reduction leading to the same covalency parameter as that previously reported in NiO and \( KNiF_{3} \) . Comparison with the isomorphous compounds \( MnCO_{3} \) and \( CoCO_{3} \) indicates in \( NiCO_{3} \) an increase of the superexchange interactions, both isotropic and anisotropic, a decrease of the spin-exchange polarization through the \( (\mathrm{CO}_{3})^{2-} \) radicals, and a substantial reduction of the covalency parameter.

I. INTRODUCTION

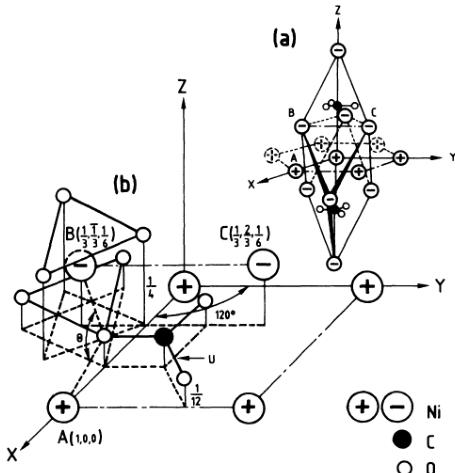

All carbonates of the iron family with \( R\overline{3}c \) trigonal symmetry are antiferromagnets at low temperature. \( ^{1} \) Neutron-diffraction experiments on powders have shown that in \( FeCO_{3} \) (Ref. 2) the antiferromagnetic moments are parallel to the trigonal axis and aligned in ferromagnetic sheets perpendicular to that axis, in the sequence + - + - [Fig. 1(a)]. On the other hand, detailed polarized neutron-diffraction experiments performed on single crystals of \( MnCO_{3} \) (Ref. 3) and \( CoCO_{3} \) (Ref. 4) reveal that, in the latter carbonates, the magnetic moments lie in ferromagnetic sheets perpendicular to the trigonal axis, along which they again alternate in the sequence + - + - [Fig. 1(a)]. Whereas both \( MnCO_{3} \) (Ref. 5) and \( CoCO_{3} \) (Ref. 6) are weak ferromagnets at \( T < T_{N} \) , \( FeCO_{3} \) does not show any spin canting down to 4 K. \( ^{7} \) These last results are in good agreement with Dzyaloshinsky's general theory \( ^{8} \) of weak ferromagnetism in antiferromagnetic compounds. In particular, in compounds of \( R\overline{3}c \) symmetry, Dzyaloshinsky's theory indicates that, in addition to the usual anisotropy forces, spin-orbit interactions may introduce an anisotropic exchange interaction which goes from a maximum value when the antiferromagnetic (AF) direction is perpendicular to the trigonal axis to zero when the AF direction is along that axis. Such an interaction tends to bring pairs of opposite moments parallel to each other and competes with the usual symmetric antiferromagnetic exchange interaction, leading to a weak ferromagnetic moment. This situation is indeed realized in \( MnCO_{3} \) (Refs. 3 and 5) and \( CoCO_{3} \) (Refs. 4 and 6), whereas weak ferromagnetism is absent in \( FeCO_{3} \) (Ref. 7) where the AF direction is along the trigonal axis. \( ^{2} \) In the case of \( NiCO_{3} \) , which is also a weak ferromagnet, \( ^{1} \) the only powder neutron-diffraction data which exist were published in 1962, \( ^{9} \) and contain poorly resolved reflections and \( \lambda/2 \) contamination. The best fit between the calculated

FIG. 1. (a) Trigonal structure of \( NiCO_{3} \) showing the antiferromagnetic piling up along the trigonal axis. (b) Part of the trigonal structure of \( NiCO_{3} \) in the case of \( u = \frac{1}{3} \) . The antiferromagnetic interactions are superexchange ones in the case of the pair A-B and through \( (\mathrm{CO}_{3})^{2-} \) radical in the case of the pair A-C.

and experimental intensities was found if the magnetic moments, still in ferromagnetic sheets aligned in the sequence + - + - along the trigonal axis [Fig. 1(a)], are at an angle 63° with that axis. Although according to Dzyaloshinsky's theory,⁸ such an AF direction still allows, in principle, the existence of weak ferromagnetism, it is a surprising result, particularly in view of the magnetic measurements,¹ which unambiguously indicate that the weak ferromagnetic moment which is developed in a direction perpendicular to the trigonal axis is the largest of all those occurring in the series of carbonates. On the other hand, in order to bring the intensities of the magnetic reflections on an absolute scale, the normalization factor used in Ref. 9 is obtained as usual² by comparing the observed and calculated intensities of the nuclear reflections, these last ones being obtained using the oxygen parameter u = 0.27,¹⁰ a value which has since been shown incorrect in MnCO₃ (Ref. 3) and CoCO₃ (Ref. 4).

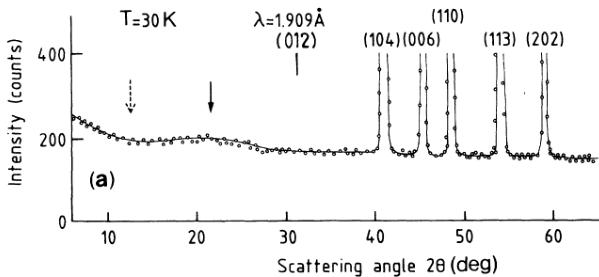

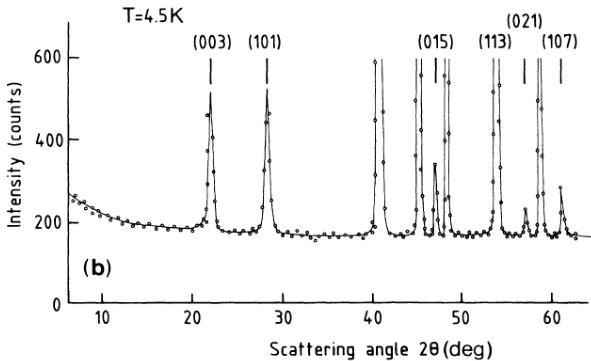

A need for additional neutron-diffraction experiments on \( NiCO_{3} \) obviously exists. We have recently performed such experiments at the Laue-Langevin Institute at Grenoble. The D1A high-resolution powder diffractometer was used at a wavelength \( \lambda=1.909\ \AA \) corresponding to the (115) reflection of a germanium monochromator; \( \lambda/2 \) contamination is thus avoided, whereas, at this wavelength, \( \lambda/3 \) contamination is negligible.

II. RESULTS

The difficulty of growing single crystals of \( NiCO_{3} \) which are not found in nature is well known. \( ^{1} \) Using hydrothermal methods, \( ^{11} \) the largest dimensions of the crystals we obtained never exceeded 0.1 mm. About 1 g of such crystals ground into a fine powder was used in the neutron-diffraction experiments. X-ray work performed at room temperature shows no impurities, all the observed reflections being found at Bragg-angle positions corresponding to the parameter values \( a_{0} \) and \( c_{0} \) ( \( a_{0}=4.609\ \AA \) , \( c_{0}=14.737\ \AA \) (Ref. 11)) of the equivalent hexagonal cell containing six \( NiCO_{3} \) units. The same conclusion is reached from the neutron-diffraction work performed down to \( T>25\ K \) [Fig. 2(a)], whereas at \( T<25\ K \) additional reflections manifest themselves which may also be indexed with the hexagonal cell of parameters \( a_{0} \) and \( c_{0} \) [Fig. 2(b)]. No preferential orientation effects are detected, measurements performed in different orientations of the sample to the counter showing no modification of the intensities of the various reflections.

Owing to their particular positions in the nuclear cell (Fig. 1), the nickel and carbon atoms contribute only to the nuclear reflections with even l, whereas the oxygen atoms, located in more general positions, also take part in the nuclear reflections with odd l as long as the pairs of h,k indices are such that \( h \neq -k \) , all these reflections satisfying the selection rule \( -h + k + l = 3n \) . With use of the well-known scattering amplitudes of Ni, C, and O ( \( b_{Ni} = 1.03 \) , \( b_{C} = 0.665 \) , \( b_{O} = 0.58 \) in \( 10^{-12} \) cm), least-squares refinements performed on the integrated intensities \( I_{Nobs} \) (Table I) at all T > 25 K lead to R = 0.8% if the oxygen parameter in \( a_{0} \) units takes the value \( u = 0.2813 \left( \pm 5 \times 10^{-4} \right) \) . This u value is the largest of all those reported in the carbonates of the iron family (Table II). It may be related to the smaller size of the \( Ni^{2+} \) ion in comparison with the size of the other

FIG. 2. (a) Part of the neutron-diffraction spectrum at 30 K. (b) Part of the neutron-diffraction spectrum at 4.5 K.

TABLE I. Intensities of the fundamental reflections (hkl).

| hkl | I_{N obs}(T=30 K) | I_{N calc} | I_{M}' |

| 012 | 0 | 0.2 | 8.33 |

| 104 | 3872 ( \( \pm \) 72) | 3894 | 5.56 |

| 006 | 483 ( \( \pm \) 32) | 489 | 1.87 |

| 110 | 625 ( \( \pm \) 35) | 601 | 2.37 |

| 113 | 2137 ( \( \pm \) 56) | 2147 | 0 |

| 202 | 385 ( \( \pm \) 30) | 371 | 1.53 |

| 024 | 630 ( \( \pm \) 35) | 630 | 2.07 |

\( M^{2+} \) ions. From these u values, the length \( r_{0} \) of the \( M^{2+} \) - \( O^{2-} \) bonds connecting every \( M^{2+} \) ion to its six nearest \( O^{2-} \) neighbors may be obtained. These values (Table II) indicate that the smallest \( r_{0} \) is found in the case of \( NiCO_{3} \) . Knowing the u value, the angle \( \theta \) made by the two bonds \( M^{2+} \) - \( O^{2-} \) joining every \( O^{2-} \) ion to its two nearest \( M^{2+} \) neighbors [Fig. 1(b)], is readily calculated from the following relation:

\[ \cos\theta=\frac{6u^{2}-6u+1-\frac{1}{6}(c/2a)^{2}}{6u^{2}-6u+2+\frac{1}{6}(c/2a)^{2}}. \quad (1) \]

The \(\theta\) values corresponding to the various carbonates are also reported in Table II, the largest one being found in the case of NiCO\(_{3}\). Having the smallest \(r_{0}\) and the largest \(\theta\), NiCO\(_{3}\) fulfills the conditions\(^{12}\) to display the strongest isotropic superexchange interactions, taking place through \(M^{2+}\)-\(O^{2-}\)-\(M^{2+}\) paths, in the series of carbonates of the iron family. This is in excellent agreement with the experimental values of the equivalent molecular fields \(H_{E}\) obtained from magnetic measurements (Table II). When spin-orbit coupling is taken into account, such an enhancement of the isotropic exchange interaction will also, by necessity,\(^{13}\) be accompanied by a simultaneous increase of the anisotropic superexchange interactions, in good agreement with the corresponding experimental values of the equivalent field \(H_{D}\) also obtained from magnetic measurements (Table II).

The additional reflections observed at \(T < 25\) K [Fig. 2(b)] may also be indexed with the hexagonal cell of parameters \(a_{0}\) and \(c_{0}\), the same selection rule \(-h + k + l = 3n\) being observed. In that temperature range, no detectable

TABLE II. Nuclear and magnetic characteristics of the carbonates of the iron family.

| u | r_{0} (\textup{\AA}) | \theta | H_{E} (kOe) | H_{D} (kOe) | |

| MnCO_{3} | 0.2698^{a} | 2.194 | 119.86^{c} | 320^{b} | 4.4^{b} |

| CoCO_{3} | 0.2754^{c} | 2.111 | 120.58^{c} | 160^{b} | 27^{b} |

| NiCO_{3} | 0.2813^{d} | 2.072 | 121.78^{c} | 240^{b} | 90^{b} |

| FeCO_{3} | 0.27^{e} | 2.128 | 120.07^{e} | 150^{f} | |

| Reference 3. | |||||

| Reference 1. | |||||

| Reference 4. | |||||

| Reference 7. |

modifications of the intensities observed at \(T > 25\) K are observed with the exception of the (113) reflection which, as previously mentioned, contains only a nuclear contribution because of the oxygen atoms. In good agreement with the published \(T_{N} = 25.2\) K, \(^{1}\) these observations may be attributed to the onset of long-range magnetic ordering and confirm the \(+\rightarrow-\) sequence of ferromagnetic sheets previously reported. \(^{2}\) Using the normalization factor resulting from the comparison between the observed and calculated nuclear intensities, the magnetic intensities may be put on an absolute scale. The experimental integrated intensities \(I_{\mathrm{obs}}\) found in Table III correspond to such values. They are compared to the calculated ones \(I_{\mathrm{calc}}\) assuming that at such \(\theta\) values and low temperature, the Debye-Waller factor keeps a value unity. We alternatively use the observed \(f_{1}\) form factor of \(\mathrm{Ni}^{2+}\) in NiO (Ref. 14) and the calculated one \(f_{2}\). \(^{15}\) Various AF directions at an angle \(\phi\) to the trigonal axis have been tried, the best agreement between the observed and calculated intensities being reached (Table III) in the case \(\phi = \pi/2\) using \(f_{1}\). The value \(\langle\sigma^{\mathrm{II}}\rangle = g\langle S_{z}^{\mathrm{II}}\rangle = 1.903\) (\(\pm 0.039\)) is then obtained. On the other hand, to the observed weak ferromagnetic moment \(\langle\sigma^{\mathrm{I}}\rangle = g\langle S_{z}^{\mathrm{I}}\rangle = 0.372\) (Ref. 1) corresponds, for \(\phi = \pi/2\) and with use of \(f_{1}\), the calculated magnetic intensities \(I_{M}^{\prime}\) (last column of Table I) which all are smaller than the statistical uncertainties (\(\pm 10\) b) due to the background fluctuations.

III. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

It is noteworthy that in \( NiCO_{3} \) , in contradiction to the value \( \phi=63^{\circ} \) reported in Ref. 9, the AF direction is perpen-

TABLE III. Intensities of the magnetic reflections in the cases \(\phi=\pi/2\) and \(\phi=63^{\circ}\) (Ref. 9); \(f_{1}\) and \(f_{2}\) are the observed (NiO, Ref. 14) and calculated (Ref. 15) form factors, respectively. The corresponding \(\langle\sigma^{\mathrm{II}}\rangle\) and \(R\) factors are also given.

| hkl | Iobs | Icalc(φ=π/2) | Icalc(φ=63°) | ||

| f1 | f2 | f1 | f2 | ||

| 003 | 220.3 (±25) | 220.9 | 258.5 | 180 | 210.7 |

| 101 | 207.4 (±24) | 206.5 | 233.3 | 244.4 | 276.3 |

| 015 | 91.7 (±20) | 96.2 | 95.2 | 87.1 | 86.2 |

| 113 | 89.3 (±19.5) | 95.9 | 89.5 | 106.3 | 99.3 |

| 021 | 38.5 (±16) | 35.1 | 32.4 | 43 | 39.6 |

| 107 | 51.2 (±17) | 50.2 | 45.8 | 43.5 | 39.6 |

| (σII) | 1.903 (±0.039) | 2.080 (±0.133) | 1.928 (±0.163) | 2.108 (±0.189) | |

| R | 2.9% | 9.8% | 15.6% | 14.2% | |

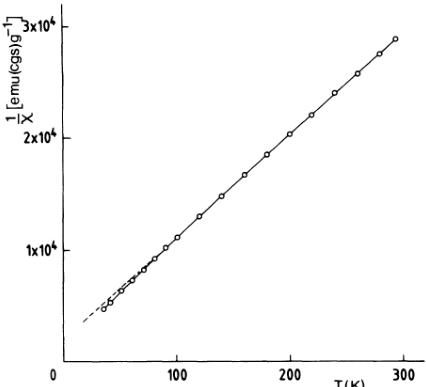

dicular to the trigonal axis as it is in \( MnCO_{3} \) (Ref. 3) and \( CoCO_{3} \) (Ref. 4). In these last carbonates, covalency effects \( ^{16} \) due to an extension of the metal-ion antibonding orbitals towards the ligands have also been measured. \( ^{3,4} \) As the experimental form factor \( ^{15} \) used here is expanded by 17% in the \( \sin\theta/\lambda \) direction relative to the \( Ni^{2+} \) free-ion values, indications also exist that, in a fashion similar to the powder neutron-diffraction experiments and subsequent discussions on \( KNiF_{3} \) (Ref. 17) and \( NiO_{x} \) \( ^{18} \) a partial covalent bonding of \( Ni^{2+} \) and ligand orbitals exists in \( NiCO_{3} \) . With use of the value g=2.299 ( \( \pm0.015 \) ) for the Landé factor obtained from susceptibility measurements performed in our laboratory (Fig. 3), a numerical evaluation of the covalency in \( NiCO_{3} \) may be derived if, in agreement with the temperature dependence of the magnetic intensities and the weak ferromagnetic moment, \( ^{1} \) we assume that magnetic saturation is achieved at 4.5 K. With

\[ \langle\sigma\rangle=[\langle\sigma^{\parallel}\rangle^{2}+\langle\sigma^{\perp}\rangle^{2}]^{1/2}=g\langle S_{z}\rangle \]

the value \( \langle S_{z}\rangle=0.843(\pm0.031) \) is obtained. The covalency parameter \( f_{0} \) may then be deduced from the following relation valid for a \( d^{8} \) ion, \( ^{17,18} \)

\[ S_{0}\left[1-\frac{\alpha}{S_{0}}\right](1-3f_{0})=\langle S_{z}\rangle\quad. \quad (2) \]

In relation (2), \( \alpha \) is the fraction of the 0-K spin deviation which in spin-wave approximation \( ^{19} \) takes the value 0.078. With \( S_{0}=1 \) , we are led to \( f_{0}=2.8\pm1.1\% \) . Using the value \( \alpha=0.064 \) obtained from Walker's perturbation theory, as was done in Ref. 17, the value \( f_{0}=3.3\pm1.1\% \) is obtained, indicating that a relative uncertainty in the correct evaluation of \( \alpha \) , due for instance to a small amount of nonsaturation at 4.5 K, would bring little change in the determination of \( f_{0} \) . Similar values of \( f_{0} \) , \( f_{0}=3.8\pm0.2\% \) and \( f_{0}=2.6\pm1.8\% \) , respectively, are found in NiO (Ref. 18) and KNiF \( _{3} \) (Ref. 17) with use of the spin-wave approximation. On the other hand, the \( f_{0} \) value obtained in the case of NiCO \( _{3} \) is about one-half of those reported for MnCO \( _{3} \) (Ref. 3) and CoCO \( _{3} \) (Ref. 4), where polarized neutron work was performed on single crystals, a technique allowing a detailed study of the spin-density maps since the weak ferromagnetic reflections are also measured. These larger \( f_{0} \) values and the observation of spin densities of opposite sign on carbon and oxygen atoms in MnCO \( _{3} \) and CoCO \( _{3} \) have since \( ^{20} \) been related to a spin-exchange polarization mechanism within the \( (\mathrm{CO}_{3})^{2-} \) radicals. This last mechanism also explains why the ferromagnetic moment resulting from a partial cancellation of these spin densities is particularly small in these carbonates. In NiCO \( _{3} \) , as a result of the larger distance between the carbon and oxygen atoms in planes perpendicular to the trigonal axis (Fig. 1), stronger superexchange interactions through \( M^{2+}-O^{2-}-(M^{\prime})^{2+} \) paths with M=A and \( M^{\prime}=B \) are expected. In addition, the exchange polarization mechanism which takes place through \( (\mathrm{CO}_{3})^{2-} \) and couples pairs of cations such as A and C (Fig.

FIG. 3. Inverse magnetic susceptibility of \( NiCO_{3} \) as a function of temperature.

1) is likely to be reduced. Let us also observe that the hump due to short-range magnetic ordering at \( T > T_{N} \) and which may be detected up to \( T \simeq 2T_{N} \) culminates at an angle position \( 2\theta \simeq 21.48^{\circ} \) [solid arrow on Fig. 2(a)]. According to the Debye formula, such a \( \theta \) value is expected for an antiferromagnetically coupled pair of magnetic moments at a distance \( d \simeq 3.62 \AA \) which is the distance between A and B [Fig. 1(b)]. Although the mechanism of the diffuse scattering at \( T > T_{N} \) in compounds of this type is certainly quite complex, it may be noticed that if the strongest AF interaction would have taken place between A and C at a distance \( 6.06 \AA \) [Fig. 1(b)], the maximum of the corresponding expected hump would have been found at an angle position \( 2\theta = 12.79^{\circ} \) [dotted arrow on Fig. 2(a)], where nothing is observed. Evidence is thus seen that in contrast to \( MnCO_{3} \) and \( CoCO_{3} \) , both isotropic and anisotropic superexchange interactions are here the leading terms in the spin Hamiltonian. The weakening of the spin-polarization effect in \( (\mathrm{CO}_{3})^{2-} \) radicals, and the subsequent reduction of the cancellation of spin densities of opposite sign on the oxygen and carbon atoms, would explain why in \( NiCO_{3} \) the ferromagnetic component is the largest of all those reported in the series of carbonates of the iron family. \( ^{1} \)

Although powder work similar to ours on \( NiCO_{3} \) allows a fair determination of the amount of covalency, more insight into the importance of the various magnetic interactions may only be obtained from polarized neutron analysis on single crystals, if these ever become available.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to Dr. A. Hewat and Mr. S. Heathman of Institut Laue-Langevin for invaluable help in collecting the neutron diffraction data.

\( ^{5} \) A. S. Borovik-Romanov, Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 36, 766 (1959) [Sov. Phys. JETP 2, 539 (1959)].

\( ^{6} \) A. S. Borovik-Romanov and V. I. Ozhogin, Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 39, 27 (1960) [Sov. Phys. JETP 12, 18 (1961)].

\( ^{7} \) I. S. Jacobs, J. Appl. Phys. 34, 1106 (1963).

\( ^{8} \) I. Dzyaloshinsky, J. Phys. Chem. Solids 4, 241 (1958).

\( ^{9} \) R. A. Alikhanov, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 17, Suppl. BIII, 58 (1962).

\( ^{10} \) R. W. Wyckoff, Crystal Structures, 2nd ed. (Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1983), Vol. 2, p. 362.

\( ^{11} \) Natl. Bur. Stand. (U.S.) Monogr. 25, Sec. 1 (1961).

\( ^{12} \) P. W. Anderson, Phys. Rev. 79, 350 (1950).

\( ^{13} \) T. Moriya, Phys. Rev. 120, 91 (1960).

\( ^{14} \) H. A. Alperin, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 17, Suppl. BIII, 12 (1962).

\( ^{15} \) R. E. Watson and A. J. Freeman, Acta Crystallogr. 14, 27 (1961).

\( ^{16} \) J. Hubbard and W. Marshall, Proc. Phys. Soc. (London) 86, 561 (1965).

\( ^{17} \) M. T. Hutchings and H. J. Guggenheim, J. Phys. C, 3, 1303 (1970).

\( ^{18} \) B. E. F. Fender, A. J. Jacobson and F. A. Wedgwood, J. Chem. Phys. 48, 990 (1968).

\( ^{19} \) P. W. Anderson, Phys. Rev. 86, 694 (1952).

\( ^{20} \) P. A. Lindgard and W. Marshall, J. Phys. C 2, 276 (1969).