| Transition Temperature | 8.5 K |

|---|---|

| Experiment Temperature | 4.8 K |

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | Pbcn (#60) |

| Magnetic Space Group | Pb'cn (#60.419) |

| Magnetic Point Group | m'mm (8.3.26) |

| Lattice Parameters | 6.79230 10.35660 6.05500 90.00 90.00 90.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1016/j.jssc.2015.09.006 |

| Reference | E.E. Rodriguez, H. Cao, R. Haiges and B.C. Melot, Journal of Solid State Chemistry (2016) 236 39-44. |

| Label | Element | Mx | My | Mz | |M| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co1 | Co | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.00 |

Single crystal magnetic structure and susceptibility of \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \)

Efrain E. Rodriguez, Huibo Cao, Ralf Haiges, Brent C. Melot

www.elsevier.com/locate/yjssc

PII: S0022-4596(15)30158-4 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2015.09.006 Reference: YJSSC19080

To appear in: Journal of Solid State Chemistry

Received date: 6 July 2015

Revised date: 3 September 2015

Accepted date: 4 September 2015

Cite this article as: Efrain E. Rodriguez, Huibo Cao, Ralf Haiges and Brent C Melot, Single crystal magnetic structure and susceptibility of \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) , Journal of Solid State Chemistry, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2015.09.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, an review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain

Single crystal magnetic structure and susceptibility of CoSe_{2}O_{5}

Efrain E. Rodriguez \( ^{b,*} \) , Huibo Cao \( ^{c} \) , Ralf Haiges \( ^{a} \) , Brent C. Melot \( ^{a,*} \)

\( ^{a} \) Department of Chemistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA

\( ^{b} \) Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, United States

\( ^{c} \) Quantum Condensed Matter Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831, USA

Abstract

The structure of \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) consists of one-dimensional ribbons of edge-sharing \( CoO_{6} \) octahedra bound together by polyanionic subunits of \( Se_{2}O_{5} \) . Previous work on polycrystalline samples reported a canted antiferromagnetic arrangement of the magnetic moments below the ordering temperature of 8.5 K. Here, we report a single crystal investigation using variable temperature and field magnetic susceptibility and low-temperature neutron diffraction to more precisely characterize the nature of the magnetic ground state of \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) . Contrary to previous reports, we find that the single crystal magnetic structure shows no cantiing of the antiferromagnetic ground state, and in the process have identified several field-induced changes to the magnetization. We discuss these results in the context of the revised magnetic structure and highlight the importance of crystal growth for the accurate characterization of these properties.

Keywords: metamagnetism, single crystal, magnetic structure PACS: 75, 75

1. Introduction

One-dimensional magnetic materials exhibiting a strong degree of anisotropy in their superexchange interactions often display novel physical properties. \( [1, 2] \) Yet, this anisotropy can present unique challenges when studying polycrystalline samples since only strongly averaged properties can be measured without accurately orienting the magnetic field along each axis of the unit cell. \( [3, 4] \) It is, therefore, critical that high quality single crystals be used to study these kinds of compounds in order to accurately evaluate and understand anisotropic physical properties.

The structure of \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) consist of one-dimensional ribbons of edge-sharing \( CoO_{6} \) octaheda bound together by polyanionic subunits of \( Se_{2}O_{5} \) These units consist of two pyramidal \( SeO_{3} \) groups that possess a stereochemically active pair of \( 4s^{2} \) electrons localized at the apex of each pyramid and point in opposite directions. [5] Previous work on polycrystalline powders of \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) reported a canted antiferromagnetic ground state below an ordering temperature of 8.5 K. Low-field magnetization measurements also indicated signs of weak ferromagnetism, but no explanation for this behavior was suggested. [6]

Here, we perform a detailed investigation into the anisotropic magnetic properties of \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) . Using neutron scattering on single crystals, we find no evidence for canting of the magnetic moments previously seen in powdered samples, but instead find a uniformly collinear antiferromagnetic structure within and between the chains with moments oriented along the a-axis. Temperature- and field-dependent magnetic susceptibility reveal four distinct high-magnetic-field induced changes to orientation of the moments, with two occurring along the a-axis and two occurring along the c-axis. We discuss these observations in the context of the anisotropic superexchange pathways that result from the chain-like topology of the crystal structure.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Single crystal growth

\( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) was prepared following a previously reported hydrothermal procedure. \( ^{[5]} \) \( SeO_{2} \) (5.0 g, Sigma-Aldrich, 99.8%) was dissolved in 15 cm \( ^{3} \) of water and combined with \( CoSO_{4}\cdot7H_{2}O \) (2.0 g, Sigma-Aldrich, \( \geq99\% \) ). The mixture was sealed in a 23-mL poly(tetrafluoroethylene)-lined pressure vessel (Parr Instruments) and heated to 200°C for 48 hours. The resulting product consisted of dark purple single crystals averaging 1.0 mm × 1.0 mm × 0.5 mm.

2.2. Single Crystal Alignment

A prism-shaped crystal specimen, approximate dimensions \( 0.240 \, mm \times 0.362 \, mm \times 0.403 \, mm \) , was affixed on a CryoLoop using Paratone N oil and mounted on a Bruker APEX DUO single crystal diffractometer with the width of the \( \chi \) -axis fixed at \( 54.74^\circ \) . The diffractometer was equipped with an APEX II

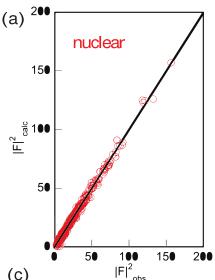

Figure 1: \( |F|_{obs}^{2} \) vs. \( |F|_{calc}^{2} \) plots from the refinement of the (a) nuclear and (b) magnetic reflections against single crystal neutron scattering data obtained from the HB-3A four-circle single-crystal diffractometer at the High-Flux Isotope Reactor at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. (c) \( |F|^{2} \) vs. \( \sin\theta/\lambda \) plot for the observed structure factors, calculated, and difference from the magnetic refinement of 93 reflections. The \( R_{F^{2}w} = 7.2\% \) for the nuclear refinement and 17.2% for the magnetic refinement.

CCD detector and an Oxford Cryosystems Cryostream 700 apparatus for low-temperature data collection. The crystal orientation matrix was determined from 36 omega scans \( (0.5^{\circ} \) width) that were collected in three orthogonal runs of 12 frames each at 100 K using Mo Kα radiation (TRIUMPH curved-crystal monochromator) from a fine-focus tube using the BIS software package.[7] The final cell constants of \( a=6.806(4) \) Å, \( b=10.375(7) \) Å, \( c=6.050(4) \) Å, \( \alpha = 90^{\circ} \) , \( \beta = 90^{\circ} \) , \( \gamma = 90^{\circ} \) , V = 427.2(8) Å \( ^{3} \) , are based upon the least-squares refinement of the XYZ-centroids of 113 reflections. The crystal faces were then indexed with the Bruker APEX2 software package[8] using a \( 360^{\circ} \) phi crystal rotation video and the crystal orientation matrix.

2.3. Physical Property Measurement

Temperature- and field dependent DC magnetization was measured on oriented single crystals using a 14 T Quantum Design PPMS equipped with a vibrating sample magnetometer. A single crystal weighing 20.5 mg was selected and affixed to a quartz rod using Duco \( ^{\circledR} \) cement and kapton tape. The flat face of the prism was measured by sandwiching the crystal between two quartz rods within a brass sample holder and securing with Duco \( ^{\circledR} \) cement.

2.4. Neutron scattering

The single crystal diffraction measurements were carried out on the HB-3A four-circle single-crystal diffractometer at the

(a)

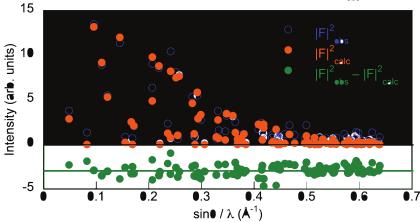

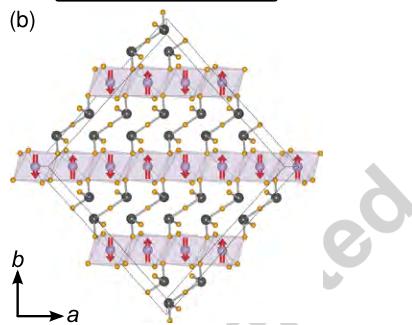

Figure 2: Illustration of the magnetic structure along the (a) b- and (b) c-axis.

High-Flux Isotope Reactor at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The neutron wavelength employed was 1.003 Å using a bent perfect Si-331 monochromator. Nuclear and magnetic reflections were taken on a four-circle goniometer with the sample at 4.8 K using a closed-cycle helium refrigerator. To obtain nuclear structural parameters and a scale factor, 346 nuclear reflections were measured up \( Q = 8.055 \, \AA^{-1} \) . The 93 magnetic reflections measured are those at k = 0 and appear at forbidden positions for the nuclear structure. To check for any incommensurability of the magnetic structure, the [010] and [030] magnetic reflections were scanned at a Q-resolution high enough to see any incommensurate structure with k = 0.002 in reciprocal lattice units. Refinements of both the nuclear and magnetic structures were carried out using the FullProf suite of programs. [9]

3. Results

3.1. Magnetic Structure Determination

The scans through the (010) and (030) reflections with the highest-Q resolution available did not show any incommensurate satellite reflections. Therefore, the magnetic structure can be described as antiferromagnetic with the magnetic propagation vector k equal to zero.

The refinement of the nuclear structure lead to a good agreement with the previously published orthorhombic \( Pbcn \) structure with the Co on the 4c site \( (0, y, 3/4) \) . The fit to the nuclear reflections are shown in the \( |F|_{obs}^{2} \) vs. \( |F|_{calc} \) plot in Figure 1a. To gauge the size of the magnetic moment accurately, the scale factor and the Co structural parameters of y and \( B_{iso} \) from the nuclear refinement were used in the magnetic fit.

The method of representations was used for fitting the magnetic reflections. For the wavevector of k = 0, space group

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

Table 1: The character table of the eight irreducible representations for magnetic ordering in \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) with a magnetic propagation vector k = 0. The characters for each representation are given for the eight symmetry elements found in the little group \( G_{k} \) . Since each irreducible representation is one-dimensional, they can be related to their respective magnetic space groups. The best fit to the neutron data was performed with \( \Gamma_{8} \) , which corresponds to magnetic space group \( Pb^{\prime}cn \) .

| Irreducible representation | 1 | 2z | 2y | 2x | \( \bar{1} \) | m_{xy} | m_{xz} | m_{yz} | magnetic space group | magnetic components allowed |

| \( \Gamma_{1} \) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Pbcn | (0, M_{y}, 0) |

| \( \Gamma_{2} \) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | |||

| \( \Gamma_{3} \) | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | Pb'c'n' | (M_{x}, 0, M_{z}) |

| \( \Gamma_{4} \) | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 1 | 1 | Pbcn' | (M_{x}, 0, M_{z}) |

Pbcn, and the magnetic Co ion on the 4c site, the BasiReps routine within FullProf returned 8 one-dimensional representations within the little group \( G_{k} \) . A full listing of the irreducible representations can be found in Table 1, and the 8th representation \( \Gamma_{8} \) is the only one that led to a reasonable fit to the neutron data. In the context of magnetic symmetry, each irreducible representation corresponds to one of the maximal magnetic space groups for the nuclear space group Pbcn. The eight possible magnetic space groups and their relation to the irreducible representations are also listed in Table 1; the MAXMAGN routine in the Bilbao crystallographic server was used to find the corresponding magnetic space groups (Ref. Perez-Mato here). The representation \( \Gamma_{8} \) corresponds to the magnetic space group \( Pb^{\prime}cn \) and constrains the magnetic moment to lie in the ac-plane. The magnetic moments can then be calculated using the Fourier method according to

\[ \mathbf{m}_{j}=\sum_{j}\mathbf{S}_{\nu}^{4}\exp(i\mathbf{G}_{m}\cdot\mathbf{r}_{j}) \quad (1) \]

where \( m_{j} \) is the moment value for an atom at position \( r_{j} \) , \( G_{m} \) is the reciprocal lattice vector corresponding to a magnetic reflection, and \( S_{\nu}^{4} \) is the spin Fourier coefficient. These coefficients can be found through linear combination of the basis functions

\[ \mathbf{S}_{\nu}^{4}=\sum_{\lambda}C_{\nu}^{4}\vec{\psi}_{\nu}^{4} \quad (2) \]

where the basis vector \( \vec{\psi}_{\nu}^{4} \) belongs to the \( \nu^{th} \) irreducible representation and is indexed by \( \lambda \) . The coefficients \( C_{\nu}^{4} \) are the only refined parameters with the neutron diffraction data set. More on the Eq. 1 and 2 and the general approach of representational analysis can be found on the works by Izyumov (Reference Izyumov book here) and Bertaut (Reference Bertaut article here). The \( \vec{\psi}_{\lambda}^{4} \) functions corresponding to \( \Gamma_{8} \) , which fit the data, are presented in Table 2.

Given the high accuracy of the scale factor from the 342 nuclear reflections, the magnetic refinement returned a moment size of \( 3.0(1)\mu_{B} \) per Co cation, which indicates all high spin \( Co^{2+} \) . The resulting fits are shown in Figure 1 where both \( |F|_{obs}^{2} \) vs. \( |F|_{calc}^{2} \) and \( |F|^{2} \) vs. \( \sin\theta/\lambda \) plots are presented.

As seen in Figure 2, the resulting magnetic structure is one in which the moments point only along the a-direction and are

Table 2: The basis functions \( \vec{\psi}_{8}^{4} \) for each Co ion site. All basis functions are real and correspond to the irreducible representation (the 8th irreducible representation) that best fit the magnetic reflections. The refined value for \( y = 0.939(1) \) .

| Co coordinates | \( \vec{\psi}_{8}^{4} \) | \( \vec{\psi}_{8}^{2} \) |

| 0, y, 3/4 | (1 0 0) | (0 0 1) |

| 1/2, -y + 1/2, 1/4 | (1 0 0) | (0 0 -1) |

| 0, -y, 1/4 | (-1 0 0) | (0 0 -1) |

| 1/2, y + 1/2, 3/4 | (-1 0 0) | (0 0 1) |

antiferromagnetically coupled along the chains parallel to the c-direction. The chains are in turn antiferromagnetically coupled to the nearest neighbor chains. The representations (irreducible representations 1, 2, 5, and 6 in Table 2) that included a moment along the b-direction all led to unstable refinements. The other four representations always included two basis functions for a moment along the a-direction and another along the c-direction. Adding a moment along the c-direction did not improve the fit to the magnetic peaks only. If \( \vec{\psi}_{8}^{2} \) had a component, this would lead to slight canting of the moment along the c-direction with antiferromagnetic coupling within the chain, but ferromagnetic coupling between nearest neighbor chains. Either way, the structure would be inconsistent with weak ferromagnetism. The invariance of the fit with respect to having a coefficient on the \( \vec{\psi}_{8}^{2} \) basis vector of Table 2 could be the reason why the magnetic structure from the current analysis is different from the one determined using powder methods in Ref. 6. Both nuclear and magnetic reflections were therefore included in order to fit any possible c-axis component. The refined value along c was less than \( 0.5 \mu_{B} \) with a standard uncertainty larger than the moment size. While including a c component did not improve the fit, it did not raise the residual of the fit either. However, a model which uses the least amount of parameters to achieve the best fit is the best model, and our single crystal diffraction data therefore supports a collinear antiferromagnetic structure.

3.2. Temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility

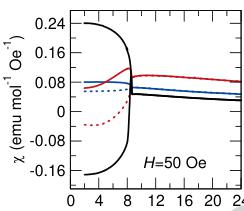

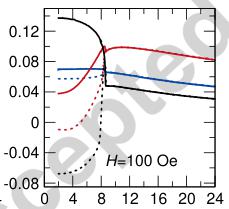

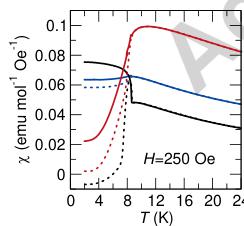

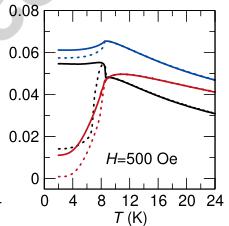

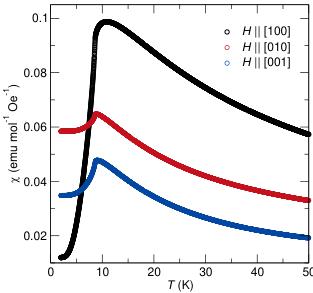

Figure 3 shows the temperature-dependent magnetic susceptibility along each axis of a representative crystal under varying strength of the applied magnetic field. As expected for a

compound with a chain-like topology, a significant degree of anisotropy can be seen between each of the axes. The a-axis shows a pronounced jump in the field-cooled susceptibility below 8.5 K when measured with fields of 50 and 100 Oe. This jump is gradually suppressed in fields of 250 and 500 Oe, and is completely suppressed in a larger field of 10 kOe (Figure 4). In contrast, the b- and c-directions both exhibit the traditional cusp that is associated with the pairing of spins into an antiferromagnetic ground state.

Considering the magnetic structure illustrated in Figure 2 only exhibits a single component to the moment oriented strictly along the a-axis, the observation of uncompensated moments below the ordering temperature is somewhat unexpected. The magnetic structure is analogous to the G-type antiferromagnetic structures of the perovskites, \( [10] \) with all of the nearest neighbor Co-Co interactions within and between the chains pointing antiparallel to each other with no uncompensated moment observable within the unit cell.

Fitting the high temperature region (200 K to 400 K) of the magnetic susceptibility collected under a field of 10 kOe to the Curie-Weiss equation, \( \chi = C/(T - \theta_{CW}) \) , provides insight into the nature of the magnetic interactions. The resulting fits give values for \( \theta_{CW} \) of -15 K, -16 K, and -62 K and effective moments of \( 5.03\mu_{B} \) , \( 4.96\mu_{B} \) , and \( 5.20\mu_{B} \) along the [100], [010], and [001] directions respectively. The effective moments are all in close agreement with the expected value of \( 5.20\mu_{B} \) typically observed for octahedrally coordinated \( Co^{2+} \) (S=3/2, L=3) with decoupled contributions from the spin and orbital components of the magnetization ( \( \mu_{L+S} = \sqrt{4S(S+1) + L(L+1)} \) ). [11] The negative sign for the fitted \( \theta_{CW} \) in all directions reflects the dom-

Figure 3: Magnetic susceptibility at various small fields. The black, red, and blue lines correspond to measurement with the field oriented along the a-, b-, and c-axes of the unit cell. The field-cooled and zero-field-cooled data are represented by solid solid and dashed lines respectively. The pronounced splitting of the zero-field- and field-cooled susceptibility along the a-axis is indicative of a ferromagnetic alignment of the spins not seen in the zero-field magnetic structure.

Figure 4: Magnetic susceptibility of the title phase collected under a field of 10 kOe. The red, black, and blue and lines correspond to measurement with the field oriented along the a-, b-, and c-axes of unit cell. Note that in large fields there is no splitting between the zfc and fc traces of the susceptibility.

inanant antiferromagnetic coupling in all directions. The larger value of \( \theta_{CW} \) observed along the c-axis reflects the stronger magnetic exchange that occurs through the shared edges of the cobalt octahedra compared to the more complex super-superexchange interactions that mediate the interchain interaction through the diamagnetic \( Se_{2}O_{5} \) units. Interestingly, the ratio of the \( \theta_{CW} \) along the chain direction (the c-axis) to the experimental ordering temperature is close to 7. This ratio, frequently referred to as the frustration index, [12, 13] indicates a moderately frustrated system and likely reflects a competition between the nearest and next-nearest neighbor spins down the length of the chain.

The observation of the ferromagnetic response was further investigated by indexing the faces of the crystal in order to understand the nature of the exposed surfaces. The crystals adopt a prism-like habit, shown in Figure 5 (a), with the b-axis composing the major flat surface with the edges of the platelet composed of a mixture of the \( [110] \) , \( [111] \) , and \( [112] \) planes. This means that the magnetic chains are run from one corner of the crystal to the next, with the terminating plane cleaving at angle such that ferromagnetic chain ends are exposed along each edge of the crystal as illustrated in Figure 5 (b). These dangling chains at the edge of the crystallites are the most likely origin of the observed ferromagnetic response in small fields with larger fields forcing the chain ends to adopt the low-energy ground expected for the bulk.

3.3. Field-dependent magnetic susceptibility

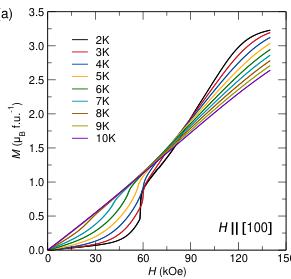

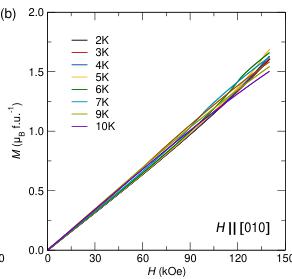

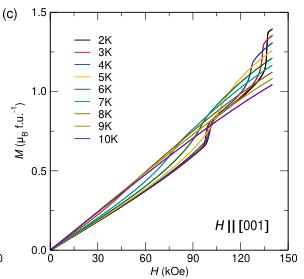

Figure 6 shows the positive quadrant of the isothermal magnetization along each of the principle crystallographic axes at various temperatures Below the ordering temperature of 8.5 K, a significant deviation from the linear response expected for an antiferromagnetic ground state is observed. These deviations are most prominent when the field is applied along the a- and c- axes, with measurements along the b-axis, which is perpendicular to the orientation of the moment and chain direction, showing no significant changes with applied field or temperature. Inspecting the derivative of the magnetization curves reveals two separate sets of field-induced transitions along a and

Figure 6: Isothermal magnetization curves obtained at various temperatures around the magnetic transition. Panels (a), (b), and (c) show data obtained with the field oriented along the [100], [010], and [001] directions respectively.

(a)

(b)

Figure 5: (a) Photograph of a representative crystal of the title phase. The two edges of the diamond face are between 0.3 mm and 0.4 mm as stated in the text. (b) Orientation of the structural topology with respect to the exposed crystal planes. The black lines represent the morphology of the crystal formed when the \( [110] \) , \( [111] \) , and \( [112] \) planes intersect. Note the ferromagnetic chain ends that are exposed around the edges of the crystal.

c. When the magnetic field is applied along the a axis, an extremely sharp upturn is observed around 60 kOe with a more shallow point of inflection occurring near 86 kOe. Similarly, applying fields of 100 kOe and 135 kOe along the c-axis results in two sharp upturns in the magnetization.

When applying fields along the a-axis, there is a clear kink in the magnetization data around 60 kOe that may be related to the breaking of the effective S=1/2 ground state commonly associated with the Kramers doublet of octahedrally coordinated \( Co^{2+} \) . [14, 15] Applying larger fields causes a steep climb in magnetization until a saturation of \( 3\mu_{B} \) is reached above fields of 90 kOe, indicating the antiferromagnetic ground state is completely broken in favor of a ferromagnetic alignment of the spins. In contrast, when the field is oriented along the c-axis, the steep changes are most likely associated with a spin flop transition of the magnetic moments away from the a-axis and onto the c. Further neutron scattering experiments in the presence of strong magnetic fields are necessary to fully understand the nature of these spins flops, and are currently being pursued.

4. Discussion

The complex magnetic behavior found in \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) can be attributed to the highly anisotropic magnetic exchange pathways in the crystal structure. The strength of the mean-field interactions along the length of the chains only appears to be a factor of three stronger than the interaction between the chains. This is the most likely origin of the moderate magnetic frustration, and could explain the complex magnetic-field dependence observed in the isothermal magnetization measurements. When the Curie-Weiss analysis is considered alongside the magnetization data, it is clear that the dominant antiferromagnetic interactions occur down the length of the cobalt chains as expected. However, the presence of multiple field-induced transitions indicates that the inter-chain superexchange interactions may not be completely negligible, with larger fields destabilizing the ground state configuration in favor of a lower energy arrangement that better minimizes competition from these interactions. The presence of multiple high-field magnetic transitions suggests that further characterization of the temperature- and field-dependent properties could yield greater insight into the interplay between all of the complex inter- and intra-chain interactions.

5. Conclusions

We have reported the observation of several field-induced changes to the magnetic order in \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) at low temperatures. Four distinct field-induced transitions be seen in the 2 K magnetization curves, with two along the a-axis and two along the c-axis, with no disruption to the antiferromagnetic being observed for fields oriented along the b-axis. These observations

were not detectable in powder samples and serves to reiterate the importance of crystal growth when studying complex magnetic properties like those reported here.

6. Acknowledgements

B. C. M. gratefully acknowledge financial support through start-up funding provided by the Dana and David Dornsife College of Letters and Sciences at the University of Southern California and Gavin Lawes for useful discussions. E. E. R. acknowledges financial support from start-up funds provided by the University of Maryland and the National Science Foundation (CAREER DMR-1455118). The research at Oak Ridge National Laboratories High-Flux Isotope Reactor is sponsored by the Scientific User Facilities Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy.

7. References

[1] S.-W. Cheong, M. Mostovoy, Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity, Nat. Mater. 6 (2007) 13–20, doi:10.1038/nmat1804.

[2] T. Kimura, Spiral Magnets as Magnetoelectrics, Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 37 (2007) 387–413, doi:10.1146/annurev.matsci.37.052506.084259.

[3] V. Franco, A. Conde, Magnetic anisotropy obtained from demagnetization curves: Influence of particle orientation and interactions, Applied Physics Letters 74 (1999) 3875–3877, doi:10.1063/1.124209.

[4] H. Lawton, K. H. Stewart, Magnetization Curves for Polycrystalline Ferromagnetics, Proceedings of the Physical Society. Section A 63 (1950) 848, doi:10.1088/0370-1298/63/8/308.

[5] W. T. A. Harrison, A. V. P. McManus, A. K. Cheetham, Synthesis and structure of cobalt diselenite, \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) , Acta Cryst. C48 (1992) 412–413, doi:10.1107/S0108270190001044.

[6] B. C. Melot, B. Paden, R. Seshadri, E. Suard, G. Néner, A. Dixit, G. Lawes, Magnetic structure and susceptibility of \( CoSe_{2}O_{5} \) : An antiferromagnetic chain compound, Phys. Rev. B 82 (2010) 014411, doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.82.014411.

[7] Bruker, Bruker Instrument Service v2012.12.0.3, 2015.

[8] Bruker, APEX2 v2014.7-1, 2015.

[9] J. Rodriguez-Carvajal, Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction, Physica B 192 (1993) 55–69, doi:10.1016/0921-4526(93)90108-I.

[10] E. O. Wollan, W. C. Koehler, Neutron Diffraction Study of the Magnetic Properties of the Series of Perovskite-Type Compounds \( [(1-x)La_{x}Ca]MnO_{3} \) , Phys. Rev. 100 (1955) 545–563, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.100.545.

[11] M. C. Day, J. Selbin, Theoretical Inorganic Chemistry, Reinhold Book Corporation, 2nd edn., 1960.

[12] A. P. Ramirez, Strongly Geometrically Frustrated Magnets, Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 24 (1994) 453–480, doi:10.1146/annurev.mes.24.080194.002321.

[13] J. E. Greedan, Geometrically Frustrated Magnetic Materials, J. Mater. Chem. 11 (2001) 37–53, doi:10.1039/b003682j.

[14] J. L. Manson, C. R. Kmety, Q.-z. Huang, J. W. Lynn, G. M. Bendele, S. Pagola, P. W. Stephens, L. M. Laible-Sands, A. L. Rheingold, A. J. Epstein, J. S. Miller, Structure and Magnetic Ordering of \( \mathrm{MII}[\mathrm{N}(\mathrm{CN})_{2}]_{2} \) (M = Co, Ni), Chemistry of Materials 10 (9) (1998) 2552–2560, doi:10.1021/cm980321y, URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/cm980321y.

[15] T. V. Brinzari, J. T. Haraldsen, P. Chen, Q.-C. Sun, Y. Kim, L.-C. Tung, A. P. Litvinchuk, J. A. Schlueter, D. Smirnov, J. L. Manson, J. Singleton, J. L. Musfeldt, Electron-Phonon and Magnetoelastic Interactions in Ferromagnetic \( \mathrm{Co}[\mathrm{N}(\mathrm{CN})_{2}]_{2} \) , Phys. Rev. Lett. 111 (2013) 047202, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.047202, URL http://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.047202.