| Transition Temperature | 110 K |

|---|---|

| Experiment Temperature | 5 K |

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | Pnma (#62) |

| Magnetic Space Group | Pn'm'a (#62.446) |

| Magnetic Point Group | m'm'm (8.4.27) |

| Lattice Parameters | 5.48890 7.70440 5.42330 90.00 90.00 90.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1016/j.jssc.2018.09.012 |

| Reference | E.C. Hunter, S. Mousdale, P.D. Battle and M. Avdeev, Journal of Solid State Chemistry (2019) 269 80-86. |

Author’s Accepted Manuscript

Magnetisation reversal in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \)

Emily C. Hunter, Simon Mousdale, Peter D. Battle, Maxim Avdeev

www.eksevier.com/locate/yjssc

PII: S0022-4596(18)30397-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2018.09.012 Reference: YJSSC20373

To appear in: Journal of Solid State Chemistry

Received date: 7 August 2018

Revised date: 6 September 2018

Accepted date: 8 September 2018

Cite this article as: Emily C. Hunter, Simon Mousdale, Peter D. Battle and Maxim Avdeev, Magnetisation reversal in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} and Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) , Journal of Solid State Chemistry, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2018.09.01

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Magnetisation reversal in Ca₂PrCr₂NbO₉ and Ca₂PrCr₂TaO₉

Emily C. Hunter, Simon Mousdale and Peter D. Battle \( ^{*} \)

Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3QR, U. K.

Maxim Avdeev

Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation, Lucas Heights, NSW 2234, Australia

School of Chemistry, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia

\( ^{*} \) author to whom correspondence should be addressed: peter.battle@chem.ox.ac.uk

Abstract

Polycrystalline samples of the perovskites \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}BO_{9} \) (B=Nb, Ta) have been synthesised using the standard ceramic method and characterized by x-ray diffraction, neutron diffraction and magnetometry. Both crystallise in the orthorhombic space group Pnma and exhibit magnetisation reversal when field-cooled in an applied field of 100 Oe. The absolute value of the negative magnetisation at 2 K in an applied field of 100 Oe is an order of magnitude greater in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) than it is for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) . Magnetometry and powder neutron diffraction showed that the \( Cr^{3+} \) cations in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) order in a \( G_{y}F_{z} \) magnetic structure below 110 and 130 K, respectively. The \( Pr^{3+} \) cations remain paramagnetic down to \( \sim \) 10 K and show no-long range order at 2 K. Both compounds show a large degree of hysteresis in \( M(H) \) , with coercive fields of 3.79 kOe and 3.03 kOe at 2 K.

Keywords: Magnetisation Reversal; Neutron Diffraction; Perovskite

Graphical abstract:

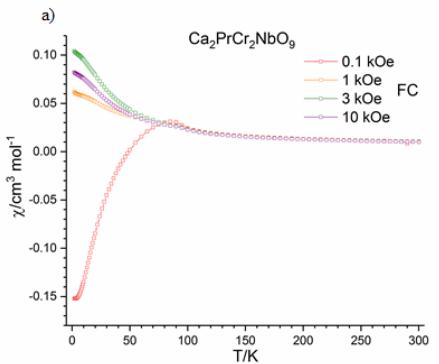

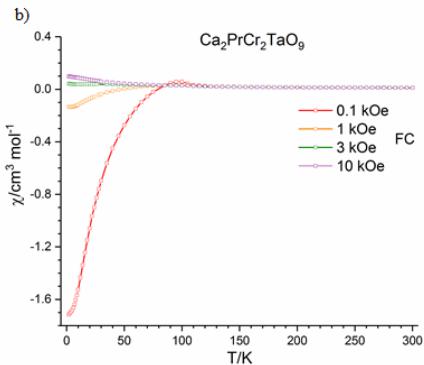

The FC molar dc susceptibility as a function of temperature measured on warming after cooling in applied fields of 0.1 (red), 1 (orange) 3 (green) and 10 kOe (purple) for a \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and b) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) .

Introduction

Insulating materials that contain cations possessing a non-zero spin quantum number generally show a positive magnetisation with respect to the direction of an externally applied magnetic field and can exhibit a wide range of magnetic properties such as paramagnetism or long-range ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic order. A negative magnetisation is normally only observed in diamagnetic or superconducting materials. However in some magnetically-ordered systems there is a cross-over from positive to negative magnetisation. This phenomenon, known as magnetisation reversal, was first observed in spinel ferrites in the 1950s \( ^{1} \) . The sign reversal in the inverse spinels \( Co_{2}VO_{4} \) and \( Co_{2}TiO_{4}^{2-} \) \( ^{3} \) , in which there are two antiferromagnetically coupled ferromagnetic sublattices, was shown to be a consequence of the different temperature dependencies and magnitudes of the \( Co^{2+} \) moments on the tetrahedral and octahedral sites, as previously hypothesised by Néel \( ^{4} \) . In an in-depth review \( ^{5} \) Kumar and Yusuf identified negative exchange coupling between canted antiferromagnetic

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

sublattices or between ferromagnetic/canted antiferromagnetic sublattices and paramagnetic sublattices as possible causes of the phenomenon. They also pointed out that it can occur in materials where there is an imbalance of spin and orbital moments and at the interface between ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases. It has been suggested that compounds possessing this property might have technological applications in the area of magnetic storage devices; particularly those based on volatile magnetic memory or thermally-assisted magnetic random-access memory \( ^{5} \) .

Magnetisation reversal has been observed in the perovskite structure, particularly in rare-earth orthochromates \( ^{6-8} \) and orthoferrites \( ^{9-11} \) but also in the double perovskite \( Sr_{2}YbRuO_{6} \) \( ^{12} \) . In the rare-earth orthochromates, which can be described by the general formula \( ACrO_{3} \) , where A is a rare-earth cation, it has been suggested that the negative magnetisation arises from negative exchange coupling between the canted antiferromagnetic Cr sublattice and the paramagnetic rare-earth sublattice \( ^{7, 13} \) . In an applied magnetic field the weak ferromagnetic moment arising from the Cr sublattice induces a negative internal field at the paramagnetic rare-earth site. The temperature at which the paramagnetic moment arising from the rare-earth sublattice is equal and opposite to the ferromagnetic moment arising from the Cr sublattice is known as the compensation temperature, or \( T_{comp} \) ; the net magnetisation is negative below this temperature. Partial substitution of the rare-earth cations at the A site and the chromium ions at the B site has been attempted in order to increase the temperature of the compensation temperature and the difference in magnitude between the extremes of the positive and negative magnetisation. For example, replacing small amounts of Cr with Fe in \( NdCrO_{3} \) to form \( NdCr_{1-x}Fe_{x}O_{3} \) increases the compensation temperature from 102 K when x = 0.05 to 169 K when x = 0.15; the value of the negative magnetisation increases concomitantly by an order of magnitude \( ^{14} \) . While \( PrCrO_{3} \) does not exhibit magnetisation reversal down to 4.2 K \( ^{15} \) , the compositions \( La_{1-x}Pr_{x}CrO_{3} \) exhibit negative magnetisation for \( 0.2 \leq x \leq 0.8^{13} \) . Li et al have recently considered the consequences of replacing \( Cr^{3+} \) cations in \( SmCrO_{3} \) by diamagnetic \( Ga^{3+} \) \( ^{16} \) . Here we investigate the effect on the magnetic properties of partially substituting both the A and B sites of \( PrCrO_{3} \) with diamagnetic cations to form \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) .

Experimental

Polycrystalline samples of \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}BO_{9} \) (B=Nb, Ta) were synthesised using the traditional ceramic method. Stoichiometric quantities of \( CaCO_{3} \) , \( Pr_{6}O_{11} \) , \( Cr_{2}O_{3} \) and \( Nb_{2}O_{5} \) or \( Ta_{2}O_{5} \)

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

were intimately ground together for 30 minutes in an agate pestle and mortar. The mixture was fired at \( 900\ °C \) for 16 hours as a loose powder, before being reground, pelletised and fired at \( 1300\ °C \) for 6 hours. It was then fired twice at \( 1350\ °C \) , for 48 hours at a time, until the reaction had gone to completion. After each firing the sample was quench-cooled to room temperature and re-ground and re-pelleted. The progress of the reaction was monitored by powder x-ray diffraction and the reaction was deemed complete when there was no further change in the x-ray powder diffraction pattern.

X-ray powder diffraction data were collected in our laboratory on a PAN'alytical Empyrean diffractometer operating with Cu \( K_{\alpha1} \) radiation over an angular range of \( 5 \leq 20^{\circ} \leq 125 \) at room temperature. Further powder diffraction data were collected with a wavelength \( \lambda = 0.8259 \) Å on the instrument I11 at the RAL Diamond Light Source. In the latter case, the samples were loaded into a 0.3 mm diameter borosilicate glass capillary and data were collected at room temperature by conducting a 30 minute constant-velocity scan over an angular range of \( 0 \leq 20^{\circ} \leq 150 \) using a Multi-Analyser-Crystal (MAC) detector. A silicon standard was used to determine the wavelength. The data were analysed using the Rietveld method \( ^{17} \) , as implemented in the GSAS program suite \( ^{18} \) , in order to determine the unit cell parameters. A cylindrical absorption correction for each sample was estimated using the Argonne X-ray Absorption calculator \( ^{19} \) . A pseudo-Voigt function \( ^{20} \) was employed to model the peak shapes and the background was modelled using a 20-term shifted Chebyshev function.

Neutron powder diffraction (NPD) data were collected on the high-resolution powder diffractometer ECHIDNA \( ^{21} \) at the Bragg institute, ANSTO, Australia. Data were collected on \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}BO_{9} \) (B=Nb, Ta) at room temperature and at 5 K with an angular range of \( 10 \leq 2\theta^{\circ} \leq 147.5 \) using a neutron wavelength of 1.622 Å. Further data were collected at 5 K over an angular range of \( 10 \leq 2\theta^{\circ} \leq 47.5 \) using a neutron wavelength of 2.4395 Å in sequential fields of 0, 0.1, 1, 3 and 10 kOe with the sample mounted in a vertical-field cryomagnet. The samples used in these measurements were pelletised to prevent movement in the applied field. They were cooled from room temperature to 5 K in zero applied field. All data were fully analysed using the Rietveld method \( ^{17} \) . A pseudo-Voigt \( ^{20} \) function was employed to model the peak shapes and the background was modelled using a 12-term shifted Chebyshev function. Regions of the diffraction profile that were contaminated by Bragg peaks from aluminium in the cryomagnet were excluded from the subsequent analysis. Additional NPD data on \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) were collected on instrument D1b at the ILL, Grenoble, at 1.5 K, 15

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

K, 25 K, 60 K and 150 K over the angular range \( 0 \leq 2\theta^{\circ} \leq 130 \) using a neutron wavelength of \( 2.52 \AA^{22} \) . The sample was loaded into a 6 mm diameter vanadium canister and data were collected for 4 hours at each temperature. All data were fully analysed using the Rietveld method, using a pseudo-Voigt function to model the peak shape and a 12-term shifted Chebyshev function to model the background.

Dc magnetometry data were collected on a Quantum Design SQUID magnetometer. The sample was compressed between two gelatin capsules and loaded into a plastic straw surrounded by eight further capsules (four each side). The two end capsules were surrounded by diamagnetic tape to prevent any movement. The measurements were taken on warming the sample through the temperature range \( 2 \leq T/K \leq 300 \) in a field of 0.1 kOe, firstly after cooling from room temperature to 2 K in a nominal field of 0 kOe (ZFC) and subsequently after cooling in the measuring field (FC). The direction of any residual field in the magnet was determined after the initial cooling and the 0.1 kOe applied field was set to be parallel to the residual field. Further FC data were collected after cooling the sample in measuring fields of 1 kOe, 3 kOe and 10 kOe. The magnetisation per formula unit (f. u.) of the sample was also measured as a function of applied field at 2 K over a field range of \( -50 \leq H/kOe \leq 50 \) after cooling in an applied field of 50 kOe.

Results

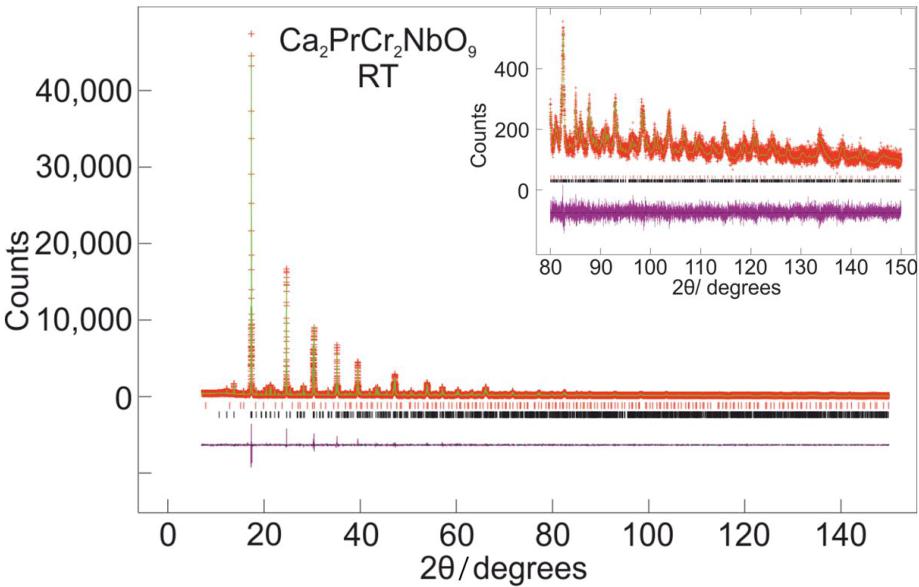

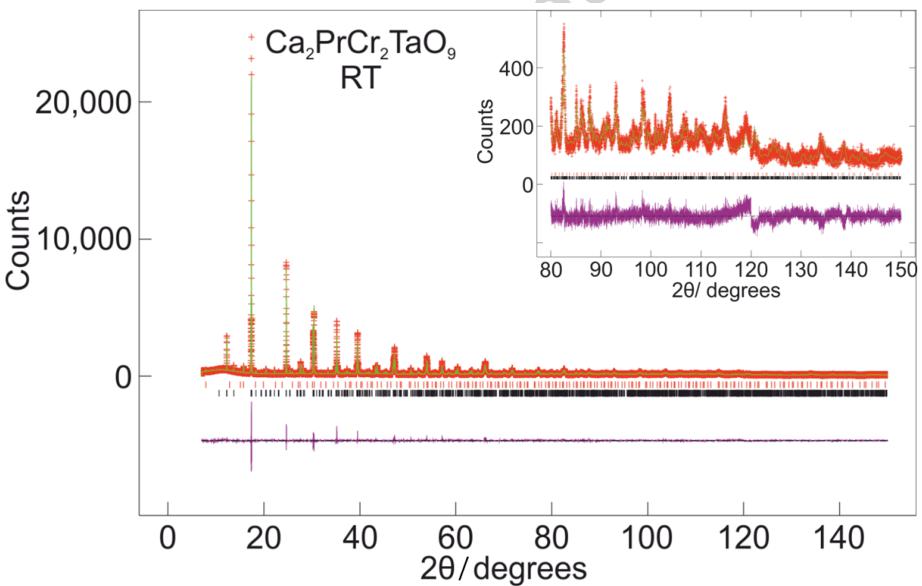

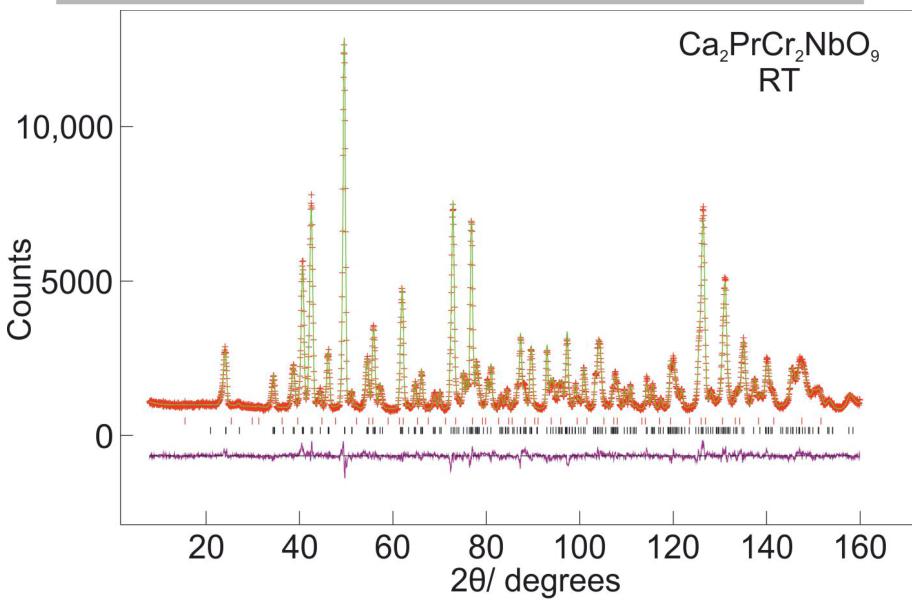

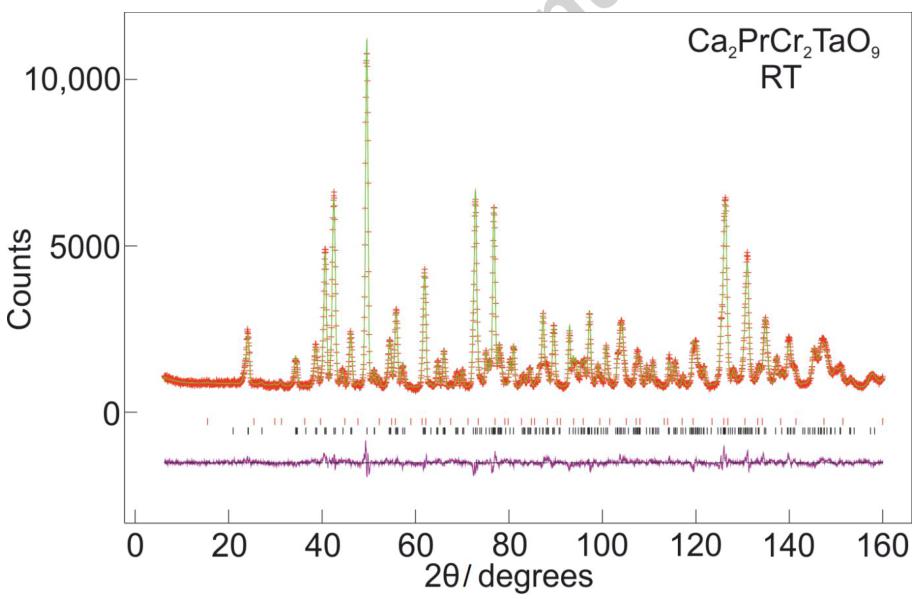

Brown polycrystalline samples of \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) were successfully synthesised. Rietveld refinement of the powder x-ray diffraction data collected on I11 revealed that both compounds crystallised in the orthorhombic space group Pnma (see Figure 1) yielding fits with \( \chi^{2}=2.150 \) ; \( R_{wp}=0.0924 \) and \( \chi^{2}=2.591 \) ; \( R_{wp}=0.1104 \) respectively. No evidence of B site cation ordering of the Cr and Nb/Ta cations was found when test refinements were carried out in the space group \( P2_{1}/n \) . \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) was found to be contaminated with 0.7 wt% \( CaPrNb_{2}O_{7} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9}\ with\ 1.4\ wt\%\ CaPrTa_{2}O_{7}\ and\ <1\ wt\%\ of\ an\ unknown\ impurity \) .

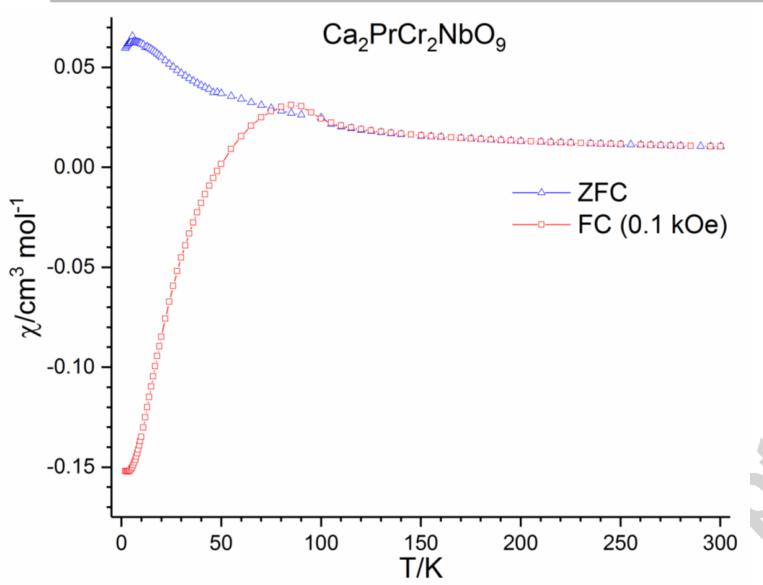

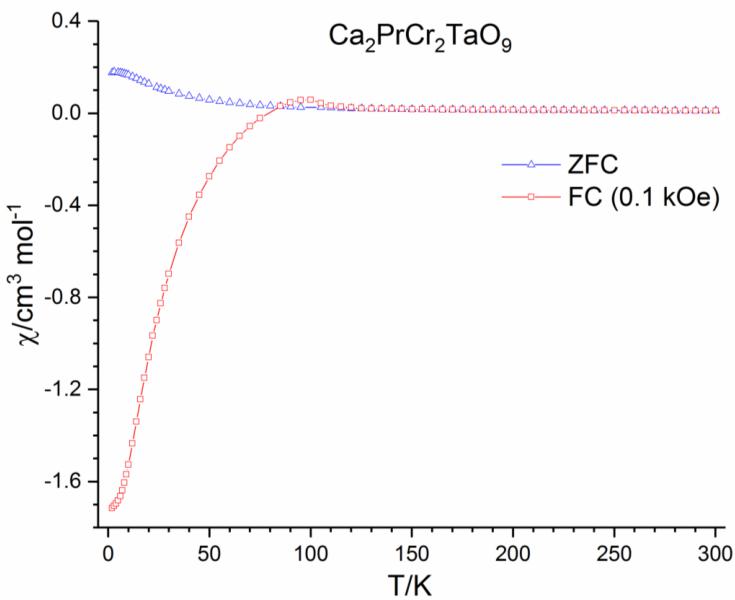

The temperature dependence of the zero field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) magnetic susceptibilities of \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) \( and Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) are shown in Figure 2. The data collected on warming in an applied field of 0.1 kOe after cooling in zero field (ZFC) show a positive susceptibility across the measured temperature range. However, after cooling in an applied field (FC) of 0.1 kOe negative values of -0.152 and -1.716 cm \( ^{3} \) mol \( ^{-1} \) were observed at 2 K for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and Ca \( _{2} \) PrCr \( _{2} \) TaO \( _{9} \) , respectively. The susceptibility of the former

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

becomes positive on warming above the compensation temperature of 50 K and reaches a maximum at 85 K before the ZFC and FC curves converge at 110 K. Similar behaviour is observed for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) with the susceptibility becoming positive on warming above the compensation temperature of 80 K, reaching a maximum at 100 K and the ZFC and FC curves converging at 130 K. Curie-Weiss fits to the data in the temperature range \( 225 \leq T/K \leq 300 \) yielded Weiss temperatures for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) , \( \theta_{W} \) , of -198(3) K and -171(3) K and Curie constants, C, of 5.12(4) and 5.00(5) cm \( ^{3} \) mol \( ^{-1} \) K \( ^{-1} \) , respectively. Assuming that the Pr(III) paramagnetic moment takes the theoretical value of 3.58 \( \mu_{B} \) , this gives the Cr(III) cations in the two compounds effective magnetic moments of 3.75(5) and 3.69(8) \( \mu_{B} \) per ion. These are close to the value of 3.873 \( \mu_{B} \) calculated for Cr(III) using the spin-only formula.

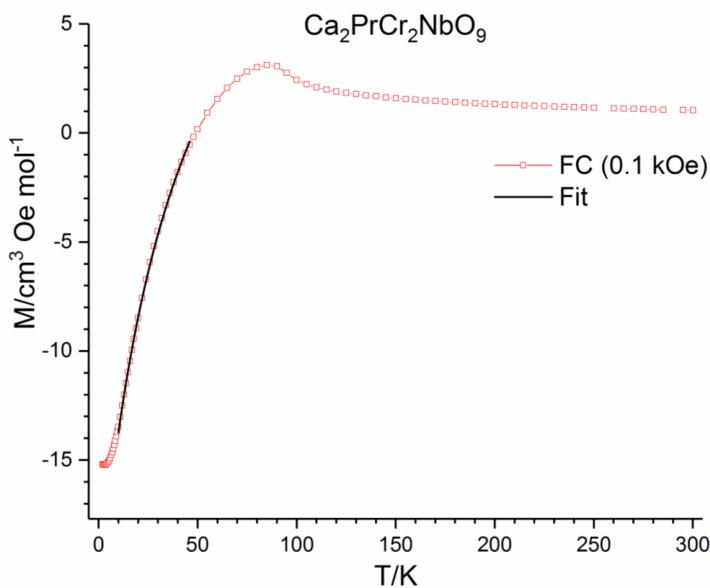

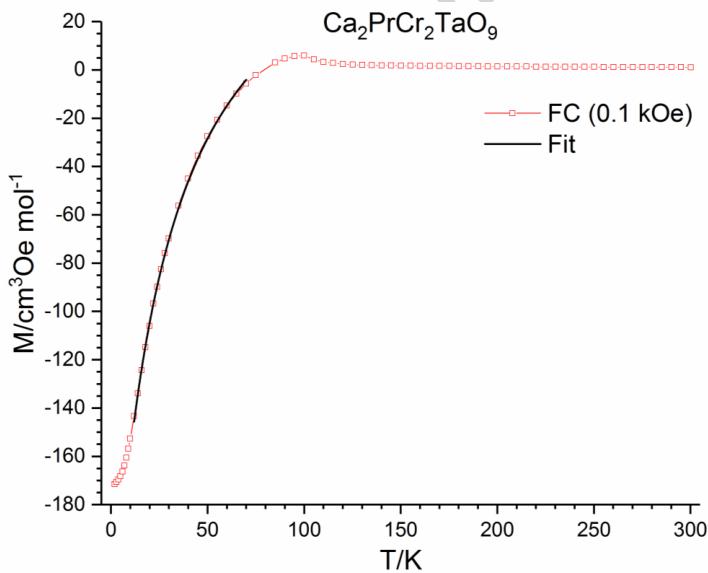

In Figure 3 the FC magnetisation collected in an applied field of \( 0.1kOe \) ( \( M = 100\gamma \) ) is fitted using equation (1) in the region \( 10 \leq T/K \leq 46 \) for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) и \( 12 \leq T/K \leq 70 \) for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) .

\[ \boldsymbol{M}=\boldsymbol{M}_{\mathrm{Cr}}+\boldsymbol{C}_{\mathrm{Pr}}(\boldsymbol{H}_{1}+\boldsymbol{H}_{\mathrm{a}})/(\boldsymbol{T}-\boldsymbol{\theta}_{\mathrm{W}}) \quad (1) \]

In equation (1) \( C_{Pr} \) is the Curie constant, \( H_{1} \) is the internal field induced by the canted Cr moments, \( H_{a} \) is the applied field and \( \theta_{W} \) is the Weiss constant. This equation was first used by Cooke et al. to model the negative magnetisation of \( GdCrO_{3} \) \( ^{7} \) . The goodness of fit of the equation to the data suggests that the negative magnetisation observed is due to the polarisation of the paramagnetic moment of \( Pr^{3+} \) by a negative internal field. The values obtained from this equation, however, are only an approximation as it assumes that \( M_{Cr} \) and \( H_{I} \) are independent of temperature. Nevertheless, the fit yielded values of \( M_{Cr} = 18(1) \) cm \( ^{3} \) Oe mol \( ^{-1} \) , \( H_{I} = -1109(80) \) Oe and \( \theta_{W} = -40(3) \) K for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) amd \( M_{Cr} = 88(4) \) cm \( ^{3} \) Oe mol \( ^{-1} \) . \( H_{I} = -5590(263) \) Oe and \( \theta_{W} = -26(1) \) K for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) ( \( C_{Pr} = 1.602 \) ; \( H_{a} = 100 \) Oe in both cases). These values are comparable to those obtained for related systems; for example for \( La_{0.5}Pr_{0.5}CrO_{3} \) \( M_{Cr} = 40 \) cm \( ^{3} \) Oe mol \( ^{-1} \) , H \( _{I} \) = -8.5 kOe and \( \theta_{W} = -3 \) K \( ^{13} \) and for \( GdCrO_{3} \) \( M_{Cr} = 100 \) cm \( ^{3} \) Oe mol \( ^{-1} \) , \( H_{I} = -1.9 \) kOe and \( \theta_{W} = -13 \) K \( ^{23} \) . The negative value of \( H_{I} \) shows that this induced moment is in the opposite direction to the applied magnetic field and to the small ferromagnetic moment arising from the canted antiferromagnetic Cr sublattice.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

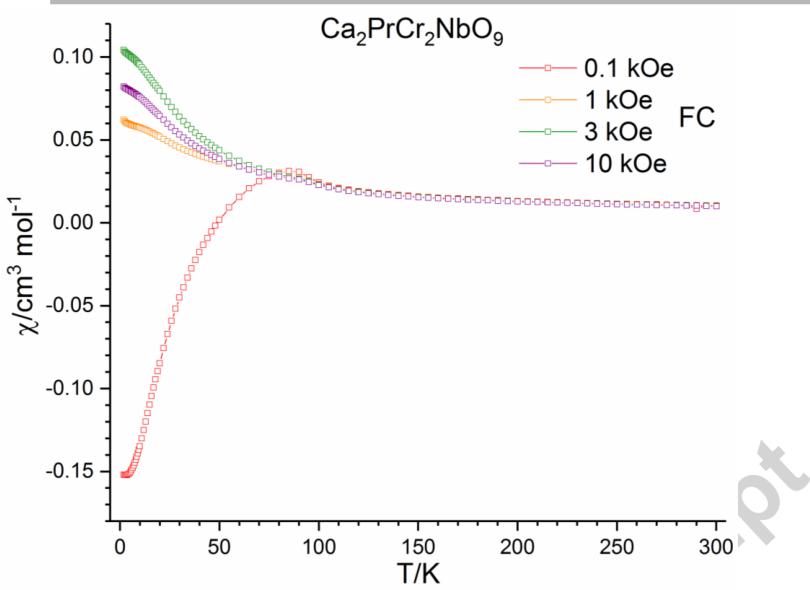

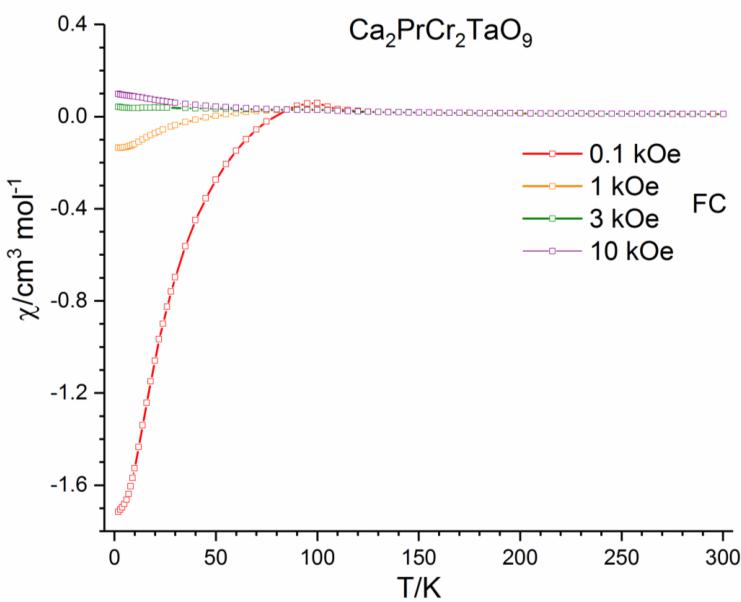

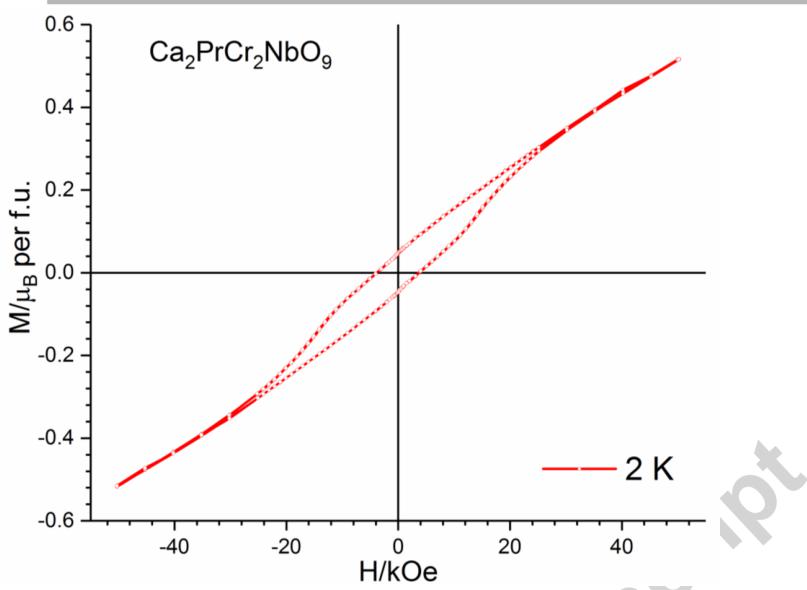

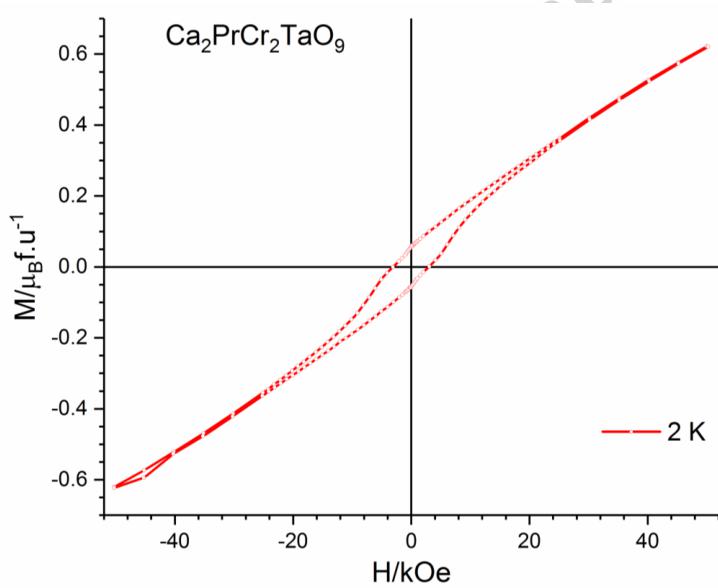

Further magnetometry data collected on warming after the samples were cooled in applied fields of 1, 3 and 10 kOe, see Figure 4, showed that at 2 K the FC susceptibility switches to become positive in an applied field of just 1 kOe for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) , while a larger field of 3 kOe is required for the switching to occur in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) . Data collected as a function of field at 2 K (see Figure 5) in the range \( -50 \leq H/kOe \leq 50 \) shows that \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) exhibits a large magnetic hysteresis with a coercive field of 3.79 kOe and a remanent magnetisation of \( 0.047 \mu_{B} \) per formula unit. \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) also displays magnetic hysteresis at 2 K with a coercive field of 3.03 kOe and a remanent magnetisation of \( 0.057 \mu_{B} \) per formula unit.

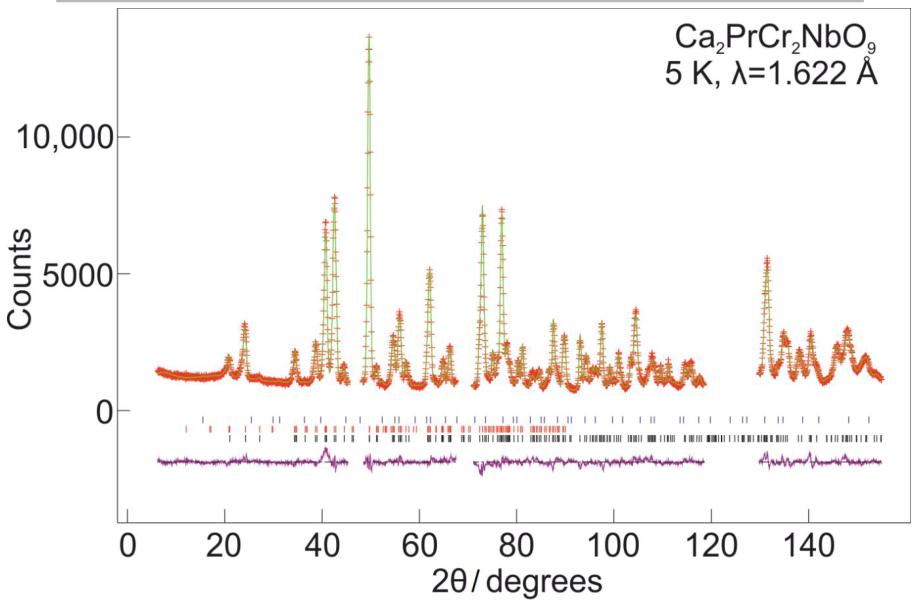

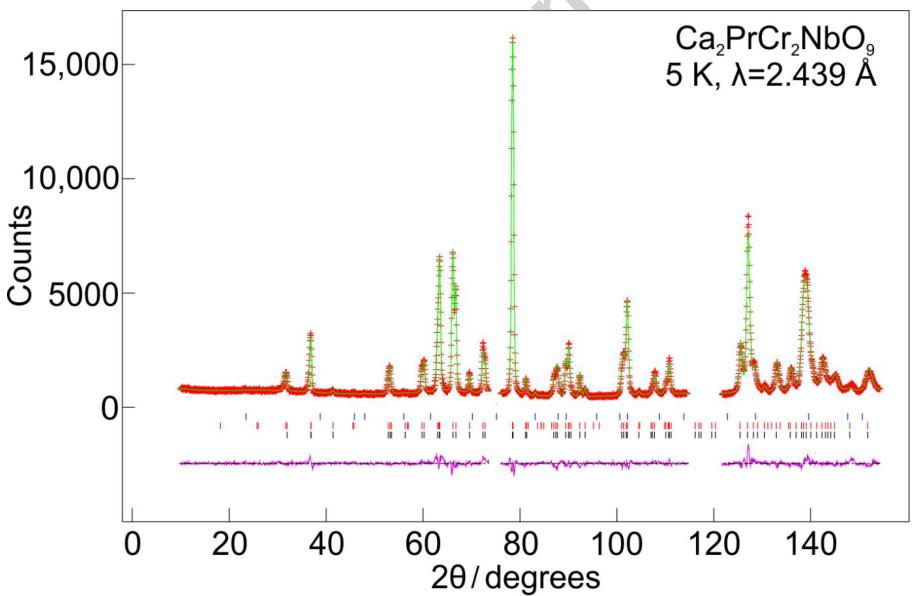

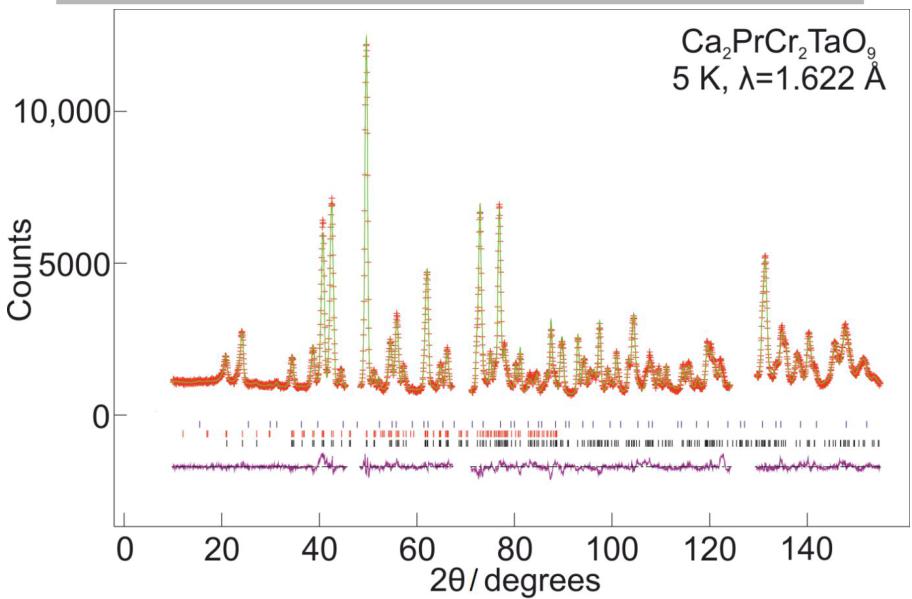

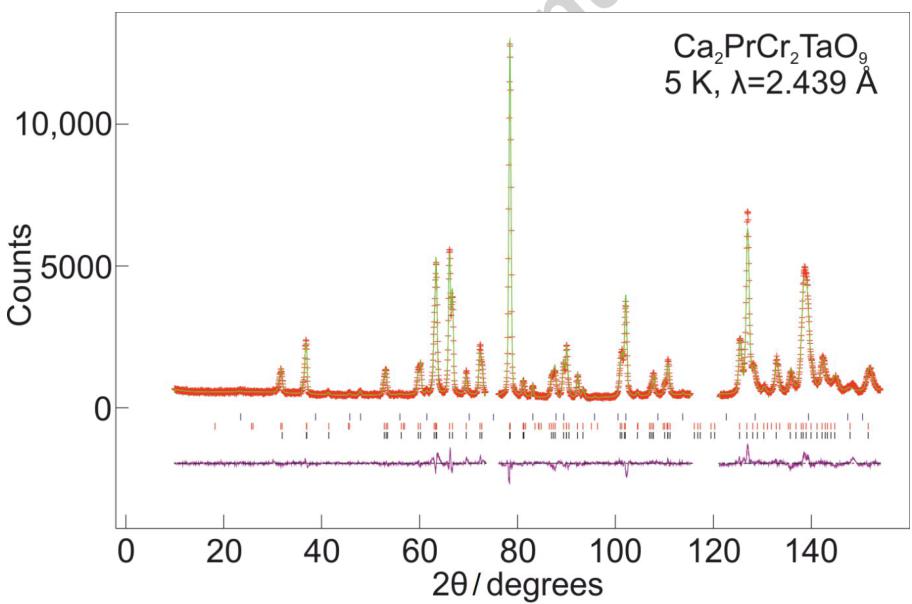

High resolution neutron diffraction data collected on ECHIDNA at room temperature confirmed that \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) crystallise in the space group Pnma, see Figure 6. The structural parameters derived from the analysis of these data are presented in Tables 1-4. In these refinements the level of contaminants was found to be 0.44 wt% \( CaPrNb_{2}O_{7} \) for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( 2.5 wt\% \) \( CaPrTa_{2}O_{7} \) for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{1}TaO_{9} \) . A combined refinement using the data collected at both wavelengths ( \( \lambda = 1.622 \) Å and \( \lambda = 2.4395 \) Å) at 5 K, see Figure 7, found the space group still to be Pnma. However, the appearance of a low angle peak corresponding to the 110 and 011 reflections and the presence of additional intensity in the 031, 130, 112 and 211 reflections suggested that long-range magnetic order was present in both samples. This magnetic Bragg scattering could be accounted for by adding a \( G_{y} \) -type magnetic phase, in keeping with the \( G_{y} \) magnetic structure determined for \( PrCrO_{3} \) from single crystal magnetisation measurements \( ^{15} \) . This gave Cr(III) ordered moments of 1.80(2) and 2.00(2) \( \mu_{B} \) for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9}\ and\ Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) , respectively. No statistically-significant ordered moment could be detected on the Pr(III) ions at the A site.

Given the field dependence of the ZFC-FC magnetometry data, further high-resolution diffraction patterns were collected in applied fields of 0.1, 1, 3 and 10 kOe. However, as shown in Figure S1, the neutron diffraction pattern in the low-angle region remained unchanged as a function of field and no changes in the magnetic structure of either compound were detected. Powder neutron diffraction data were collected on a different sample of \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) on D1b down to a lower temperature of 1.5 K, but again, no magnetic ordering of the Pr(III) ions could be detected. The refined Cr(III) moment remained unchanged between 1.5 K and 25 K, was slightly reduced at 60 K and had disappeared by 150 K. Full details of the D1b measurements are given in the electronic supporting information.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

Discussion

Unlike \( LaSr_{2}Cr_{2}SbO_{9} \) , where a high degree of cation ordering over the two B sites results in long-range ferrimagnetic order \( ^{24} \) , \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) possess no cation ordering at either the A or B site. Given that there is only one B site in the unit cell it would be more accurate to express their formulae in single perovskite form as \( Ca_{2/3}Pr_{1/3}Cr_{2/3}Nb_{1/3}O_{3} \) and \( Ca_{2/3}Pr_{1/3}Cr_{2/3}T_{a/3}O_{3} \) , but we have multiplied the formulae by three for notational simplicity. \( Cr^{3+} \) and \( Sb^{5+} \) are closer in size than \( Cr^{3+} \) and \( Ta^{5+} \) or \( Nb^{5+} \) so the absence of B site cation order must be due to the difference in the nature of \( d^{0} \) and \( d^{10} \) cations rather than to differences in size or charge alone. A similar effect is observed for \( Sr_{2}FeBO_{6} \) (B=Sb, Nb, Ta); \( Sr_{2}FeSbO_{6} \) adopts the space group \( P2_{1}/n \) with the \( Fe^{3+} \) and \( Sb^{5+} \) cations partially ordered over the two crystallographically-distinct six-coordinate sites \( ^{25} \) whereas there is no B site cation ordering in \( Sr_{2}FeNbO_{6} \) and \( Sr_{2}FeTaO_{6} \) and both compounds adopt the space group Pnma (or \( Pbnm \) ) \( ^{26} \) . The loss of cation order causes a change in the magnetic properties of the compounds with \( Sr_{2}FeSbO_{6} \) exhibiting long-range antiferromagnetic order below 35.5 K whereas \( Sr_{2}FeNbO_{6} \) and \( Sr_{1}FeTaO_{6} \) are spin glasses. In \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and Ca \( _{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) there is still long-range magnetic order despite the loss of cation order. The antiferromagnetic order is also G-type, as observed in \( LaSr_{2}Cr_{2}SbO_{9} \) , but there is no occupancy imbalance of the magnetic cations to produce ferrimagnetic behaviour. Instead a weak ferromagnetic moment is produced from a slight canting of \( CrO_{6} \) octahedra, which causes an initial increase in the susceptibility below the ordering temperature of the Cr sublattice. The origin of this ferromagnetic component is discussed below.

Key bond lengths and angles for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \(Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9}\) at room temperature and 5 K are listed in Tables 3 and 4. They are close to those published for \( PrCrO_{3}^{27} \) and are nearly identical to each other, which is not surprising as \( Nb^{5+} \) and \( Ta^{5+} \) have the same Shannon ionic radius of \( 0.64\ \AA^{28} \) . Compared to \( LaSr_{2}Cr_{2}SbO_{9} \) the average B-O bond lengths are similar ( \( 1.973\ \AA \) c.f. \( \sim1.978 \) ) but the replacement of Sr with Ca (and La with Pr) shortens the average A-O bond length. The

From the values extracted from the fit to the magnetisation data, the net ferromagnetic moment arising from the Cr sublattice in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) is \( \sim3.5 \) times greater than it is for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) (and this leads to a larger induced negative internal field at the A site and

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

consequently a greater negative magnetisation. However the absolute value of \( H_{I} \) extracted from the fit appears to be an overestimation as an applied field of 1 kOe is enough to flip the direction of the Pr moment in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and an applied field of 3 kOe flips the Pr moment in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) despite the respective internal fields being -1.1 kOe and -5.6 kOe. It is likely that the value of \( H_{I} \) varies as a function of applied field – for \( La_{0.5}Pr_{0.5}CrO_{3} \) the value of \( H_{I} \) varies between 4 and 13 kOe in the range \( 20 \leq H_{a} \leq 1000 Oe^{13} \) .

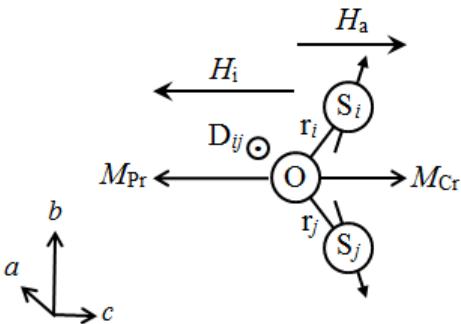

The Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DM), or antisymmetric exchange interaction, is believed to cause the spin canting that gives rise to the small net ferromagnetic moment in the Cr sublattice. It is given by the following equation where \( D_{ij} \) is a constant vector and \( S_{i} \) and \( S_{j} \) are neighbouring magnetic spins.

\[ \boldsymbol{H}_{D M}=\boldsymbol{D}_{i j}\cdot(\boldsymbol{S}_{i}\times\boldsymbol{S}_{j}) \quad (2) \]

When the magnetic interaction between the two neighbouring ions is facilitated by a single third ion via magnetic superexchange, as it is for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) , the orientation of \( D_{ij} \) is perpendicular to the triangle spanned by B-O-B or \( D_{ij} \propto r_{i} \times r_{j}^{29} \) where \( r_{i} \) and \( r_{j} \) are polar vectors between the bridging anion and the magnetic ions \( S_{i} \) and \( S_{j} \) , see Figure 8. In the space group Pnma the Dzyaloshinskii vector, \( D_{ij} \) , lies parallel to the a axis and \( S_{i} \) and \( S_{j} \) are antiparallel along b so the ferromagnetic component arising from the canting of the \( Cr^{3+} \) moments would thus be expected to lie parallel to the c axis \( ^{30} \) . In the case of \( PrCrO_{3} \) , single crystal magnetisation measurements showed that the canting angle of the Cr sublattice was only 18 mrad \( ^{15} \) and this ferromagnetic component was too weak to be detected in our NPD data. However, as a consequence of its presence the magnetic structure is more fully described as \( G_{y}F_{z} \) .

Looking at Table 4 the B-O-B bond angles in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) are essentially identical, as are the B-O bond lengths in Table 3, so the reason for the increased DM interaction and spin canting in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) compared to \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) is unclear. No magnetic ordering of the Pr ions was detected in the powder neutron diffraction data down to 1.5 K for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) in 5 K for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) . In the susceptibility data for both compounds the Pr moments deviate away from Curie-Weiss behaviour below about 10 K to form a plateau but it is unclear whether the Pr spins freeze or saturate at this temperature. It would be beneficial to study single crystal samples of \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and Ca \( _{2} \) PrCr \( _{2} \) TaO \( _{9} \) to elucidate further the magnetic structure.

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

The absolute value of the negative magnetisation increases with increasing Pr content in the series \( La_{1-x}Pr_{x}CrO_{3} \) \( 0.2 \leq x \leq 0.8 \) from 20 to \( 400 \, cm^{3} \, Oe \, mol^{-1} \) at 2K when \( H_{a} = 100 \, Oe^{31} \) . Our largest value for the absolute negative magnetisation at 2 K with \( H_{a} = 100 \, Oe \) is for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) at \( 171.6 \, cm^{3} \, Oe \, mol^{-1} \) . This compares favourably with \( La_{1.6}Pr_{0.4}CrO_{3} \) , which has a higher Pr content but a lower absolute value of the negative magnetisation of \( \sim 100 \, cm^{3} \, Oe \, mol^{-1} \) \( ^{13} \) . The absolute value of the negative magnetisation at 2 K for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) is comparable to that of \( La_{1.8}Pr_{0.2}CrO_{3} \) . Diluting the B site with a diamagnetic cation causes a substantial decrease in \( T_{N} \) from 237 K for \( PrCrO_{3} \) \( ^{15} \) to 110-130 K for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) , and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) . The cation disorder on the B site also means that the ordered Cr(III) moment refined from the powder neutron diffraction data is smaller than expected at \( 1.80(2) \, \mu_{B} \) for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( 2.00(2) \, \mu_{B} \) for \( Ca_{2}PrPr_{2}TaO_{9} \) as some of the antiferromagnetically ordered domains are too small to be detected within the length scale of powder neutron diffraction. Similarly reduced moments have been observed for other \( A_{3}B_{2}B^{\prime}O_{9} \) type systems, for example \( Sr_{3}Fe_{2}MoO_{9} \) \( ^{32} \) and \( SrLa_{2}FeCoSbO_{9} \) \( ^{33} \) , even when there is cation disorder on only one of two distinct B sites. \( LaSr_{2}Cr_{2}SbO_{9} \) , in which the B sites are partially ordered, also has a low refined ordered Cr(III) moment of \( 2.17(1) \, \mu_{B} \) \( ^{24} \) . Given that the magnetic ordering of the Cr sublattice induces the negative internal field at the A site, the reduction in \( T_{N} \) on magnetically diluting the B site also causes a reduction in \( T_{comp} \) compared to related systems \( ^{6} \) , \( ^{7, 13} \) . Therefore co-doping the orthochromates with diamagnetic elements enhances the absolute value of the negative magnetisation, but also lowers \( T_{N} \) and \( T_{comp} \) .

Conclusion

Novel compositions \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and Ca \( _{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) were successfully synthesised and found to crystallise in the space group Pnma. Both compounds show magnetisation reversal with compensation temperatures of 50 K and 80 K, respectively. The origin of the negative magnetisation appears to lie in negative exchange between the small ferromagnetic moment arising from the Cr sublattice and the paramagnetic Pr moments, which obey a modified Curie-Weiss law above 10 K. The absolute value of the negative magnetisation is an order of magnitude greater for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) than it is for \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) . We believe that this is the first time negative magnetisation has been observed in an orthochromate where both the A and B sites have been partially substituted with a diamagnetic cation, providing a new method of tuning the negative magnetisation of other orthochromates.

Acknowledgments

We thank the EPSRC for financial support under grant EP/M018954/1 and Diamond Light Source Ltd (EE13284), the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) and the Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL) for the award of beamtime. We also thank Dr E. Suard for experimental assistance on D1b and Dr C Murray for support on I11.

References

-

Nagata, T., Rock Magnetism. second ed.; Maruzen Co.: Tokyo, 1961.

-

Menyuk, N.; Dwight, K.; Wickham, D. G., Magnetization Reversal and Asymmetry in Cobalt Vanadate (IV). Physical Review Letters 1960, 4, 119-120.

-

Sakamoto, N., Magnetic Properties of Cobalt Titanate. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 1962, 17, 99-102.

-

Néel, L., Propriétés magnétiques des ferrites ; ferrimagnétisme et antiferromagnétisme. Ann. Phys. 1948, 12, 137-198.

-

Kumar, A.; Yusuf, S. M., The phenomenon of negative magnetization and its implications. Physics Reports 2015, 556, 1-34.

-

Cao, Y.; Cao, S.; Ren, W.; Feng, Z.; Yuan, S.; Kang, B.; Lu, B.; Zhang, J., Magnetization switching of rare earth orthochromite \( CeCrO_{3} \) . Applied Physics Letters 2014, 104, 232405.

-

Cooke, A. H.; Martin, D. M.; Wells, M. R., Magnetic interactions in gadolinium orthochromite, \( GdCrO_{3} \) . Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics 1974, 7, 3133.

-

Su, Y.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Z.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Cao, S., Magnetization reversal and \( Yb^{3+}/Cr^{3+} \) spin ordering at low temperature for perovskite \( YbCrO_{3} \) chromites. Journal of Applied Physics 2010, 108, 013905.

-

Jeong, Y. K.; Lee, J.-H.; Ahn, S.-J.; Jang, H. M., Temperature-induced magnetization reversal and ultra-fast magnetic switch at low field in \( SmFeO_{3} \) . Solid State Communications 2012, 152, 1112-1115.

-

Yuan, S. J.; Ren, W.; Hong, F.; Wang, Y. B.; Zhang, J. C.; Bellaiche, L.; Cao, S. X.; Cao, G., Spin switching and magnetization reversal in single-crystal \( NdFeO_{3} \) . Physical Review B 2013, 87, 184405.

-

Huang, R.; Cao, S.; Ren, W.; Zhan, S.; Kang, B.; Zhang, J., Large rotating field entropy change in \( ErFeO_{3} \) single crystal with angular distribution contribution. Applied Physics Letters 2013, 103, 162412.

-

Ravi, P. S.; Tömyc, C. V., Observation of magnetization reversal and negative magnetization in \( Sr_{2}YbRuO_{6} \) . Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2008, 20, 235209.

-

Yoshii, K.; Nakamura, A.; Ishii, Y.; Morii, Y., Magnetic Properties of La \( _{1-x} \) Pr \( _{x} \) CrO \( _{3} \) . Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2001, 162, 84-89.

-

Bora, T.; Ravi, S., Sign reversal of magnetization and tunable exchange bias field in \( NdCr_{1-x}Fe_{x}O_{3} \) (x=0.05–0.2). Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2015, 386, 85-91.

-

Gordon, J. D.; Hornreich, R. M.; Shtrikman, S.; Wanklyn, B. M., Magnetization studies in the rare-earth orthochromites. V. \( TbCrO_{3} \) and \( PrCrO_{3} \) . Physical Review B 1976, 13, 3012-3017.

-

Li, H.; Liu, Y. Z.; Xie, L.; Guo, Y. Y.; Ma, Z. J.; Li, Y. T.; He, X. M.; Liu, L. Q.; Zhang, H. G., The spin-reorientation magnetic transitions in Ga-doped \( SmCrO_{3} \) . Ceramics International 2018, 44, 18913-18919.

-

Rietveld, H. M., A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. Journal of Applied Crystallography 1969, 2, 65-71.

-

Larson, A. C.; Von Dreele, R. B., Los Alamos Natl. Lab. Rep. LAUR 1994, 86-748.

-

Argonne National Laboratory Compute X-ray Absorption. http://11bm.xray.aps.anl.gov/absorb/absorb.php

-

David, W., Powder diffraction peak shapes. Parameterization of the pseudo-Voigt as a Voigt function. Journal of Applied Crystallography 1986, 19, 63-64.

-

Liss, K.-D.; Hunter, B. A.; Hagen, M. E.; Noakes, T. J.; Kennedy, S. J., Echidna-the new high-resolution power diffractometer being built at OPAL. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2006, 385-386, 1010-1012.

-

Battle, P. D.; Hunter, E. C.; Suard, E. Negative Magnetisation in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) . Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL) doi:10.5291/ILL-DATA.5-31-2550.

-

Yoshii, K., Magnetic Properties of Perovskite \( GdCrO_{3} \) . Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2001, 159, 204-208.

-

Hunter, E. C.; Battle, P. D.; Paria Sena, R.; Hadermann, J., Ferrimagnetism as a consequence of cation ordering in the perovskite \( LaSr_{2}Cr_{2}SbO_{9} \) . Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2017, 248, 96-103.

-

Kashima, N.; Inoue, K.; Wada, T.; Yamaguchi, Y., Low temperature neutron diffraction studies of \( Sr_{2}FeMO_{6} \) (M=Nb, Sb). Applied Physics A 2002, 74, s805-s807.

-

Cussen, E. J.; Vente, J. F.; Battle, P. D.; Gibb, T. C., Neutron diffraction study of the influence of structural disorder on the magnetic properties of \( Sr_{2}FeMO_{6} \) (M=Ta, Sb). Journal of Materials Chemistry 1997, 7, 459-463.

-

Prado-Gonjal, J.; Schmidt, R.; Romero, J.-J.; Ávila, D.; Amador, U.; Morán, E., Microwave-Assisted Synthesis, Microstructure, and Physical Properties of Rare-Earth Chromites. Inorganic Chemistry 2013, 52, 313-320.

-

Shannon, R., Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallographica Section A 1976, 32, 751-767.

-

Keffer, F., Moriya Interaction and the Problem of the Spin Arrangements in \( \beta \) MnS. Physical Review 1962, 126, 896-900.

-

Amow, G.; Zhou, J. S.; Goodenough, J. B., Peculiar Magnetism of the \( Sm_{(1-x)}Gd_{x}TiO_{3} \) System. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2000, 154, 619-625.

-

Yoshii, K.; Nakamura, A., Reversal of Magnetization in \( La_{0.5}Pr_{0.5}CrO_{3} \) . Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2000, 155, 447-450.

-

Viola, M. C.; Alonso, J. A.; Pedregosa, J. C.; Carbonio, R. E., Crystal Structure and Magnetism of the Double Perovskite \( Sr_{2}Fe_{2}MoO_{9} \) : A Neutron Diffraction Study. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 2005, 2005, 1559-1564.

-

Tang, Y.; Hunter, E. C.; Battle, P. D.; Hendrickx, M.; Hadermann, J.; Cadogan, J. M., Ferrimagnetism as a Consequence of Unusual Cation Ordering in the Perovskite \( SrLa_{2}FeCoSbO_{9} \) . Inorganic Chemistry 2018, 57, 7438-7445.

Table 1 – Structural parameters of \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) at 300 K and 5 K in zero field (Space Group Pnma)

ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT

| 300 K | 5 K | ||

| a/ Å | 5.4895(1) | 5.48888(8) | |

| b/ Å | 7.7187(2) | 7.7044 (1) | |

| c/ Å | 5.4363(1) | 5.42328(9) | |

| V/ ų | 230.342(8) | 229.344(6) | |

| Rwp | 0.0461 | 0.0521 | |

| Ca/Pr | x | 0.0380(3) | 0.0383 (3) |

| 4e | y | ¼ | ¼ |

| z | -0.0080(5) | 0.9933(4) | |

| Uiso/ Ų | 0.0157(4) | 0.0133(4) | |

| Ca Occupancy | ½ | ½ | |

| Pr Occupancy | ½ | ½ | |

| Cr/Nb1 | Uiso/ Ų | 0.0020(2) | 0.0047(3) |

| 4d (0 0 ½) | Cr Occupancy | ½ | ½ |

| Nb Occupancy | ½ | ½ | |

| O1 | x | 0.4822(2) | 0.4817(2) |

| 4e | y | ¼ | ¼ |

| z | 0.0731(3) | 0.0753(3) | |

| Uiso/ Ų | 0.0056(3) | 0.0066(3) | |

| O2 | x | 0.2098(2) | 0.2090(2) |

| 8e | y | 0.5392(1) | 0.5398(1) |

| z | 0.2089(2) | 0.2083(2) | |

| Uiso/ Ų | 0.0069 (2) | 0.0082(3) |

Table 2 – Structural parameters of \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) at 300 K and 5 K in zero field (Space Group Pnma)

| 300 K | 5 K | |

| a/ Å | 5.4916(1) | 5.49132(8) |

| b/ Å | 7.7224(1) | 7.7091(1) |

| c/ Å | 5.4386(1) | 5.42625(9) |

| V/ ų | 230.642(7) | 229.711(7) |

| Rwp | 0.0465 | 0.0577 |

| Ca/Pr | 0.0373(3) | 0.0373 (3) |

| 4e | y | \( \frac{1}{4} \) | \( \frac{1}{4} \) |

| z | -0.0080(5) | 0.9914(5) | |

| \( U_{\text{iso}}/\text{Å}^2 \) | 0.015(2) | 0.0122(4) | |

| Ca Occupancy | \( \frac{2}{3} \) | \( \frac{2}{3} \) | |

| Pr Occupancy | \( \frac{1}{3} \) | \( \frac{1}{3} \) | |

| Cr/Ta1 | \( U_{\text{iso}}/\text{Å}^2 \) | 0,0015(2) | 0.0016(3) |

| 4d (0 0 ½) | Cr Occupancy | \( \frac{2}{3} \) | \( \frac{3}{3} \) |

| Nb Occupancy | \( \frac{1}{3} \) | \( \frac{3}{3} \) | |

| O1 | x | 0.4814(2) | 0.4819(2) |

| 4e | y | \( \frac{1}{4} \frac{1}{4} \) | \( \frac{1}{4} \frac{1}{4} \) |

| z | 0.0726(3) | 0.0752(3) | |

| \( U_{\text{iso}}/\text{Å}^3 \) | 0.0052(2) | 0.0041(3) | |

| O2 | x | 0.2095(2) | 0.2087(2) |

| 8e | y | 0.5394(1) | 0.5400(1) |

| z | 0.2090(2) | 0.2073(2) | |

| \( U_{\text{iso}}/\text{Å}^4 \) | 0.0065(2) | 0.0065(3) |

Table 3 – Bond lengths ( \( \mathring{A} \) ) in Ca \( _{2} \) PrCr \( _{2} \) NbO \( _{9} \) and Ca \( _{2} \) PrCr \( _{2} \) TaO \( _{9} \) at 300 K and 5 K in zero field.

| Ca2PrCr2NbO9 | Ca2PrCr2TaO9 | |||

| 300 K | 5 K | 300 K | 5 K | |

| Ca/Pr - O1 | 2.384(3) | 2.360(3) | 2.388(3) | 2.372(3) |

| Ca/Pr - O1 | 2.478(2) | 2.474(2) | 2.478(2) | 2.483(2) |

| Ca/Pr - O1 | 3.083(2) | 3.088(2) | 3.084(2) | 3.084(2) |

| Ca/Pr - O1 | 3.087(3) | 3.099(3) | 3.086(3) | 3.089(3) |

| Ca/Pr - O2 | 2.386(2) | 2.380(2) | 2.382(2) | 2.369(2) |

| Ca/Pr - O2 | 2.386(2) 2.383(2) | 2.380(2) 2.383(2) | 2.382(2) 2.383(2) | 2.369(2) 2.383(2) |

| Ca/Pr - O2 | 2.633(2) | 2.634(2) | 2.636(2) | 2.635(2) |

| Ca/Pr - O2 | 2.633(3) | 2.634(2) | 2.636(2) | |

| Ca/Pr - O2 | 2.695(2) | 2.687(2) | 2.699(2) | 2.694(2) |

| Ca/Pr - O2 | 2.695(2) | 2.687(2) | 2.699(2) | 2.694 |

| < Ca/Pr - O> | 2.646 | 2.647 | 2.642 | |

| Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O1 | 1.9725(3) | 1.9715(3) | 1.9732(3) | 1.9725(3) |

| Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O2 | 1.9794(9) | 1.9780(8) | 1.9800(9) | 1.9797(8) |

| ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT | ||||

| Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O2 | 1.9806(9) | 1.9802(8) | 1.9825(9) | 1.9826(9) |

| <Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O> | 1.9775 | 1.9766 | 1.9786 | 1.9783 |

Table 4 – Bond angles ( \( ^{\circ} \) ) in \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) at 300 K and 5 K in zero field.

| Ca2PrCr2NbO9 | Ca2PrCr2TaO9 | |||

| 300 K | 5 K | 300 K | 5 K | |

| O1 - Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O2 | 90.35(6) | 90.47(5) | 90.35(6) | 90.35(5) |

| O1 - Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O2 | 90-99(7) | 90-88(6) | 91-18(7) | 90-88(6) |

| O2 - Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O2 | 90-79(1) | 90-71(1) | 90-82(1) | 90-71(1) |

| < O - Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O> | 90-71 | 90-69 | 90-78 | 90-65 |

| Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O1 - Cr/(Nb/Ta) | 156.07(9) | 155.36(8) | 156.15(9) | 155.42(8) |

| Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O2 - Cr/(Nb/Ta) | 154.57(6) | 154.17(5) | 154.45(5) | 153.92(5) |

| < Cr/(Nb/Ta) - O - Cr/(Nb/Ta) > | 155.32 | 154.77 | 155.30 | 154.67 |

Figure Captions

Figure 1 - Observed (red crosses) and calculated (green line) synchrotron x-ray diffraction profiles of a) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and b) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) collected at room temperature on I11 and fitted using the space group Pnma. Reflection markers are shown top to bottom for \( CaPrB_{2}O_{7} \) (red) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}BO_{9} \) (black) where for a) B=Nb and for b) B=Ta.

Figure 2 - The ZFC and FC molar dc susceptibility and of a) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} and b) \) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) measured in an applied field of 100 Oe as a function of temperature.

Figure 3 – The FC magnetisation fitted to equation (1) of a) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and b) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{8} \) measured in an applied field of 100 Oe as a function of temperature

Figure 4 - The FC molar dc susceptibility as a function of temperature measured on warming after cooling in applied fields of 0.1 (red), 1 (orange) 3 (green) and 10 kOe (purple) for a) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) , and b) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} $ . --- ## ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Figure 5 - The magnetisation per formula unit of for a) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and b) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) as a function of magnetic field at 2 K.

Figure 6 - Observed (red crosses) and calculated (green line) neutron powder diffraction profiles of a) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) , and b) \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \), at room temperature. Data were collected on ECHIDNA using a wavelength of 1.622 Å and fitted using the space group Pnma. Reflection markers are shown for \( CaPrB_{2}O_{7} \) (red) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}BO_{9} \) (black) where for a) B=Nb and for b) B=Ta.

Figure 7 - Observed (red crosses) and calculated (green line) neutron powder diffraction profiles of \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}NbO_{9} \) and \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}TaO_{9} \) at 5 K. Data were collected on ECHIDNA using wavelengths of 1.622 Å (for a) and c)) and 2.439 Å (for b) and d)) and refined simultaneously for each compound in the space group Pnma. Reflection markers are shown for \( CaPrB_{2}{O}_{7} \) (blue), magnetic \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}BO_{9} \) (red) and structural \( Ca_{2}PrCr_{2}BO_{9} \) (black), where for a) and b) B=Nb and for c) and d) B=Ta.

Figure 8 – Direction of the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya vector, \( D_{ij} \) , the weak ferromagnetic component, \( M_{Cr} \) , and the internal field, \( H_{I} \) in relation to the Pnma unit cell, which polarises the Pr moment, \( M_{Pr} \) , in a low applied field, Ha. \( S_{i} \) and \( S_{j} \) are nearest neighbour Cr ions and \( r_{i} \) and \( r_{j} \) are polar vectors between \( S_{i} \) and \( S_{j} \) and the connecting oxygen anion.

a)

b)

Figure 1

a)

b)

Figure 2

a)

b)

Figure 3

a)

b)

a)

b)

Figure 5

a)

b)

Figure 6

a)

Figure 7

Figure 8

Highlights:

• Highlights of Hunter, Mousdale, Avdeev and Battle

• Field dependent magnetisation reversal

• Canted antiferromagnetic \( G_{y}F_{2} \) magnetic structure

• Polarisation of paramagnetic \( Pr^{3+} \) moment by negative internal field