| Transition Temperature | 110 K |

|---|---|

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | P63/mmc (#194) |

| Magnetic Space Group | P63'/m'm'c (#194.268) |

| Magnetic Point Group | 6'/m'mm' (27.5.104) |

| Lattice Parameters | 5.66900 5.66900 24.30400 90.00 90.00 120.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2007.12.032 |

| Reference | O. Mentre, M. Kauffmann, G. Ehora, S. Daviero-Minaud, F. Abraham and P. Roussel, Solid State Sciences (2008) 10 471-475. |

| Label | Element | Mx | My | Mz | |M| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co1 | Co | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.61 | 0.61 |

| Co2 | Co | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.21 | 2.21 |

| Co3 | Co | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

Structure, dimensionality and magnetism of new cobalt oxyhalides

Olivier Mentré \( ^{*} \) , Matthieu Kauffmann, Ghislaine Ehora, Sylvie Daviero-Minaud, Francis Abraham, Pascal Roussel

UCCS, Equipe de Chimie du Solide, UMR 8181, ENSCL – Université de Lille 1, BP 90108, 59652 Villeneuve d'Ascq Cedex, France

Received 5 September 2007; received in revised form 20 December 2007; accepted 22 December 2007 Available online 3 January 2008

Abstract

Our investigation of the \( Ba-Co-X \) (X = F, Cl, Br) systems has led to a number of new mixed-valent \( Co^{III}/Co^{IV} \) materials that have turned out to display complex magnetic properties. Here, we present a review of recent results about their crystallographic, magnetic and electric characteristics by comparison with several related compounds (including the \( BaCoO_{3-\delta} \) polytypes).

From the structural point of view, the concerned compounds and their dimensionality can be deduced from each other by the reorganization of structural blocks isolated by anionic layers. These blocks contain linear (trimeric or tetrameric) cobalt based sub-units of primary importance in the field of pseudo-1D materials. We have investigated the particular dependence of the magnetic orderings on the connectivity of the concerned blocks and basic rules can be announced, highlighting the role of the inter-block connectivity on the local Co moments and on the sign and strength of the magnetic exchanges.

© 2008 Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.

Keywords: \( BaCoO_{3} \) ; Cobaltite; Oxyhalides; Magnetic structure; Dimensionality

1. Introduction

In addition to their potential use in the field of cathode materials for lithium batteries \( [1] \) , cobaltites have been intensively studied for their magnetic properties mainly driven by the ability of cobalt cations to exhibit various electronic configurations, namely high spin (HS), low spin (LS) and intermediate spin (IS) depending on the temperature, pressure or local chemical environment. About that last point, \( RECoO_{3} \) cobaltite (RE = rare earth) have been highlighted as key materials in the understanding of the so-called “chemical pressure” effect \( [2] \) . This interest has been recently renewed by the discovery of both superconductivity \( [3] \) and attractive ThermoElectric Power (TEP) \( [4] \) in 2D \( Na_{x}CoO_{2} \) bronzes and their hydrate derivatives. Furthermore, great TEP has also been measured along the pertinent direction of 1D Co-based materials such as \( Ca_{3}Co_{2}O_{6} \) \( [5,6] \) . These recent features have led to intensive investigations on the chemical/physical properties of 1D or quasi-1D Co-based compounds such as the 2H- \( BaCoO_{3} \) \( [7] \) or \( BaCoO_{3-\delta} \) polymorphs \( [8,9] \) and to the prospect for new cobaltites with original crystal structures \( [10,11] \) . Here, we present recent results on a series of new mixed-valence \( Co^{III/IV} \) oxyhalide materials that contain linear 1D sub-units of face-sharing octahedra. This paper gives an overview of recent results on these related materials. Especially, it focuses on the relationship between the structural connectivity of the sub-units and their magnetic properties. As a powerful tool, the refined magnetic structures depict what is really going on and helps to rule on empirical laws. Then, due to the presence of similar elementary blocks, they appear as key materials for the understanding of a wide range of related compounds.

2. Linear Co-based sub-units in oxides

State of the art: (i) The 2H-BaCoO \( _{3} \) is formed of isolated columns of face-sharing Co \( ^{IV} \) O \( _{6} \) octahedra and so represents the archetype of the so-called 1D structural type with LS Co \( ^{IV} \) , S = 1/2. The intra-chain interactions are preferentially

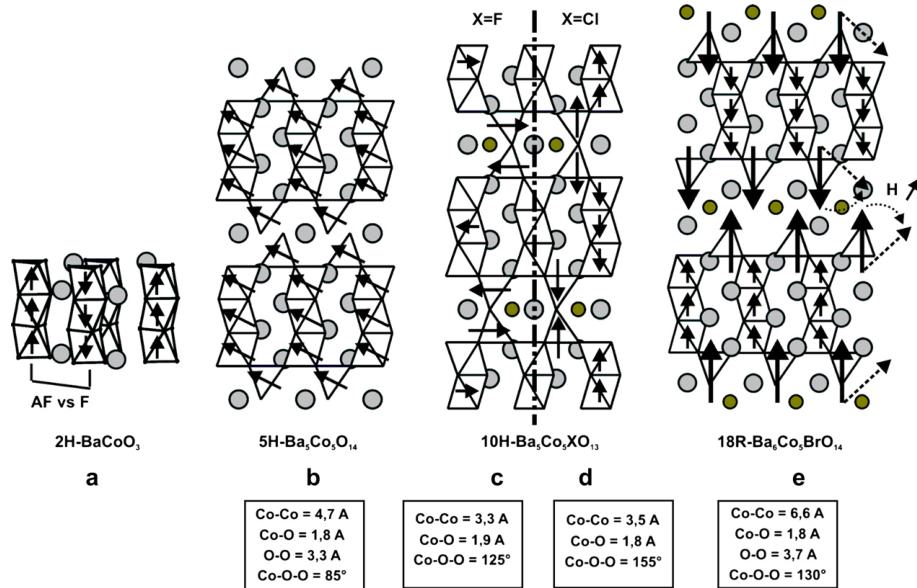

ferromagnetic along c and a competition between F and AF inter-chain interactions produces a weak ferromagnet at low temperature, i.e. \( M^{ST} = 0.15 \mu B/Co \) [7,12], Fig. 1a. However, the possibility of super-paramagnetism between non-interacting ferromagnetic clusters embedded in a non-ferromagnetic matrix has been recently argued [13]. (ii) The introduction of ordered oxygen vacancies leads to two 5H- and 12H-BaCoO \( _{3-\delta} \) polymorphs that display linear \( [Co_{3}O_{12}] \) and \( [Co_{4}O_{15}] \) face-sharing octahedra oligomers with terminal tetrahedra [14,15]. The magnetic structure described for the ferromagnetic 5H-BaCo \( ^{+3.6}O_{2.8} \) [8] shows magnetic moments of 3.1–3.5 \( \mu \) B (octahedral Co \( ^{III/IV} \) ) and 4.2 \( \mu \) B (tetrahedral Co \( ^{IV} \) ). The moments are tilted of 63(2)° with respect to the c axis. The weak unsaturated moment of 1.7 \( \mu \) B/Co at 16 T may result either from the 63° canting angle likely for the creation of hard domain walls or by a strong magnetic anisotropy along the chains [8,9]. The magnetic structure of the ferromagnetic 12H-BaCoO \( _{2.6} \) may be questionable, considering that it has been refined in the early 1980s [14]. (iii) There are not so many undoped materials with units of such dimensionality. However, it is worth mentioning the \( A_{n+2}B'B_{n}O_{3n+3} \) series which display various 1D sequences of face-sharing \( B'O_{6} \) prisms and \( BO_{6} \) octahedra depending on n [16]. Many of these compounds show incommensurate modulated structures and are not the best candidates for the rational understanding of their properties. However, the n=1 term with A=Ca and B=B'=Co corresponds to the largely studied \( Ca_{3}Co_{2}O_{6} \) compound. Here, HS prismatic \( Co^{3+} \) (S=2) and LS octahedral \( Co^{3+} \) (S=0) alternate along infinite chains. HS \( Co^{3+} \) has a strong anisotropy which creates an Ising-like situation and a giant orbital momentum [17]. HS \( Co^{3+} \) are ferromagnetically coupled along c (intra-chain) while the interchain couplings are AF, so leading to frustration effects and to possible ferrimagnetism [18]. However, under an applied field the spins align with a net moment of 5 \( \mu \) B/f.u. at saturation, very close to their expected value taking into account the orbital contribution [19]. Finally, note that the magnetic properties of all these compounds are rather complex and that no definitive consensus has been set yet.

3. Linear Co-based sub-units in oxyhalides

3.1. Introduction of \( [BaOX]^{-} \) layers

Starting from the \( BaCo_{3-\delta}^{-} \) polymorphs, the replacement of the central deficient \( [BaO_{2}]^{2-} \) layer by a \( [BaOX]^{-} \) layer (X = Cl, F) leads to new oxyhalide polytypes [20–22]. The structural modification consists of the (1/3, 2/3, 0) shearing in the \( (a,b) \) plane of isolated 2D blocks into a 3D edifice driven by the \( [BaOX]^{-} \) layers, Fig. 1b–d. To honour their bond valence, the monovalent X species of the \( [BaOX]^{-} \) layers adopt a penta-coordinated \( XBa_{5} \) bipyramid while in \( [BaO_{2}]^{2-} \) layers, the \( O^{2-} \) anions bond a tetrahedral cobalt to balance its charge. DFT calculations based on the two structural types with either a central \( [BaOX] \) or a central \( [BaO_{2}] \) layer unambiguously show the more stable 3D structure for oxyhalide and 2D

Fig. 1. Crystal, magnetic structure and geometrical features at the inter-block interface for (a) 2H-BaCoO₃, (b) 12H-BaCoO₃-δ, (c–d) Ba₆Co₆XO₁₅, and (e) Ba₇Co₆BrO₁₅,5.

form for the oxide [22]. In addition, recent \( {}^{19} \) F NMR experiments in the oxyfluorides show the presence of F \( ^{-} \) in a unique crystallographic position, i.e. solely in the layer.

3.2. Introduction of \( [Ba_{2}O_{2}Br]^{-} \) double layers

The case of \( X = Br^{-} \) is different, due to its critical ionic radius \( (r(\mathrm{F}^{-}) = 1.33 \, \text{\AA}, r(\mathrm{Cl}^{-}) = 1.81 \, \text{\AA}, r(\mathrm{Br}^{-}) = 1.96 \, \text{\AA}, \mathrm{C.N.} = \mathrm{VI}) \) . Double layers \( [Ba_{2}O_{2}Br]^{-} \) are created with the same charge as that of \( [BaOX]^{-} \) layers. The parent 2D blocks are now sheared in the \( (a,b) \) planes and pushed aside along c according to \( (1/3, 2/3, z) \) translation, Fig. 1e. The blocks appear isolated, but despite the Co–Co separation between blocks of \( \sim 6.6 \, \AA \) , the 3D magnetic ordering persists somewhat different, see below. The crystal structures and preliminary magnetic investigation of \( Ba_{2}Co_{6}BrO_{16.5} \) and \( Ba_{6}Co_{5}BrO_{14} \) with tetrameric and trimeric linear sub-units, respectively, are detailed in Ref. [23].

The six new compounds \( Ba_{5}Co_{5}^{3-4}XO_{13} \) , \( Ba_{6}Co_{6}^{3-3.33}XO_{15.5} \) (X = Cl \( ^{-} \) , F \( ^{-} \) ), \( Ba_{7}Co_{6}^{3-3.33}BrO_{16.5} \) and \( Ba_{6}Co_{6}^{5-3.4}BrO_{14} \) have been structurally and physically characterized. They crystallize in a hexagonal-related system, \( a \sim 5.7 \AA \) and c depends on the anionic layers' stacking sequence. In all of them, the Co–O distances are roughly comparable to those reported for \( BaCoO_{2.8} \) , i.e. shorter Co–O bonds ( \( \sim 1.89 \AA \) ) and longer Co–O bonds ( \( \sim 1.93 \AA \) ) for the central and the external octahedra of the linear sub-units, respectively; short Co–O bonds ( \( \sim 1.8 \AA \) ) for the tetrahedral cobalt. ND data and redox titration indicate a charge ordering with segregation of octahedral \( Co^{III} \) and tetrahedral \( Co^{IV} \) in the X = Cl \( ^{-} \) and F \( ^{-} \) cases. Identical results have been assumed for the bromides. This result involves the presence of lacunar \( [BaO_{3-\delta}] \) layer in the tetrameric compounds, but a partial hole-doping ( \( Co^{IV} \) ) of the \( Co_{3}^{III}O_{12}/Co_{4}^{III}O_{15} \) units cannot be fully excluded.

4. Magnetic properties

Due to the changes in the dimensionality, i.e. the connection between identical blocks, it appears rather interesting to compare the magnetism of these series of oxyhalides to those of their oxide analogues. The former all exhibit a paramagnetic → antiferromagnetic transition and the magnetic structures have been refined from ND data at 1.4 K. In all the cases, the 2D blocks are ferromagnetic while the inversion of the spins occurred at the tetrahedron–tetrahedron junction through stronger (connected cases) or weaker (disconnected cases) AF Co–Co exchanges. DFT calculations on \( Ba_{6}Co_{6}ClO_{15.5} \) confirms this strength in the \( Co_{2}O_{7} \) dimers [24,25] while the two oxybromide compounds are particular cases which deserve a special attention. The main magnetic characteristics of the six compounds are listed in Table 1 and immediately lead to important conclusions.

4.1. IS tetrahedral \( Co^{IV} \)

The attribution of Intermediate Spin (IS) for the tetrahedral \( Co^{IV} \) ( \( e_{1}^{3}2_{2}^{e} \) , S = 3/2) has been recently argued on the basis of local distortion caused by the splitting of the tetrahedral oxygen vertices in the [BaOX] layers for \( Ba_{6}Co_{6}ClO_{15.5} \) . This result appears valid for the series of halogeno-cobaltites, comforting the values of the refined moments for \( Co^{IV} \) .

Paramagnetic characteristics and refined moments below \( T_{N} \) from neutron data for the six concerned Ba–Co oxyhalides

| Compound Cell, S.G. | Paramagnetic data | Magnetic structure | ||||

| \( \mu_{\text{eff}} \) ( \( \mu \) B/f.u.) | \( \theta_{\text{CW}} \) (K) | Interpretation | \( T_{\text{N}} \) (K) | \( k_{\text{vector}} \) | Refined moments ( \( \mu \) B) | |

| Ba \( _{6} \) Co \( _{6} \) ClO \( _{15.5} \) | 11.26 | -983 | Tetra.: 2Co \( ^{IV} \) IS (S = 3/2) | AF | Tetra.: 1 2.85(7) | |

| a = 5.671(1) c = 14.456(3) | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.: 2Co \( ^{III} \) L \( _{S} \) (S = 0) | 135 | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.: 1 0-(0-54(9))a | |||

| P-6m2 | \( \epsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.: 2Co \( ^{III} \) H \( _{S} \) (S = 2) | [0,0/1,2] | \( \epsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.: 1 0-(0-53(9))a | |||

| Ba \( _{5} \) Co \( _{5} \) ClO \( _{13} \) | 9.21 | -766 | Tetra.: 2Co \( ^{IV} \) IS (S = 32) | AF | Tetra.: 1 2.21(7) | |

| a = 5.698(1) c = 24.469(3) | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.: 1Co \( ^{III} \) L \( _{S} \) (S = 0) 110 | 110 | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.: 1 0-(3-0.35(8))a | |||

| P6 \( _{3} \) /mmc | \( \epsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.: 1Co \( ^{III} \) H \( _{S} \) (S = 2) [0,0,0] | [0,0,0] | \( \epsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.: 1 0-0.61(7))a | |||

| Ba \( _{6} \) Co \( _{6} \) F0 \( _{15.5} \) | 6.82 | -278 | Tetra.: 2Co \( ^{IV} \) IS (S = 2/3) | AF | Tetra.: 1 2.50(4) | |

| a = 5.668(1) c = 14.227(2) | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.:2Co \( ^{III} \) L \( _{S} \) (S = 0)[126 | 126 | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.: 0 | |||

| P-6m2 | \( \varepsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.: 2Co \( ^{III} \) L \( _{S} \) (S = 0) [0,0,1/2] | [0,0,1/2] | \( \epsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.: 0 | |||

| Ba \( _{5} \) Co \( _{5} \) F0 \( _{13} \) | 6.97 | -311 | Tetra.: 2Co \( ^{IV} \) IS (S = 1/2) | AF | Tetra.: 1.94(4) | |

| a = 5.689(1) c = 23.700(2) | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.:1Co \( ^{III} \) L \( _{S} \) (S = 0) 122 | 122 | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.: 0.24(4) | |||

| P6 \( _{3} \) /mmc | 55 | \( \epsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.: 2Co \( ^{III}L \) _{S} (S = 0) [0,0,0] | [0,0,0] | \( \epsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.:0 | ||

| Ba \( _{7} \) Co \( _{6} \) BrO \( _{16.5} \) | 7.65 | |||||

| a = 5.666(1) c = 33.367(2) | Tetra.: 2Co \( ^{IV} \) IS (S = 5/2) | Spin-flop | Tetra.: 1 3.42(5) | |||

| P6 \( _{3} \) /mmc | 7.98 | 45 | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.: 2Co \( ^{II} \) L \( _{S} \) (S = 0) [0,0,0] | 50 | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) Oct.: 1 0.58(5) | |

| Ba \( _{6} \) Co \( _{5} \) BrO \( _{14} \) | 7.98 | 45 | Tetra.: 2Co \( ^{IV} \) IS (S = 7/2) | Spin-flop | Tetra.: 1 0.51(7) | |

| a = 5.657(1), c = 43.166(2) | \( \epsilon_{\text{ent}} \) OOct.: 1Co \( ^{III} \) L \( _{S} \) (S = 0) | 45 | Tetra.: 1 3.36(7) | |||

| R-3m | \( \epsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.: 3Co \( ^{III} \) L \( _{S} \) (S = 0) [1,0,3/2] | [0,0,3/2] | \( \epsilon_{\text{dg}} \) Oct.: 1 1.05(8) | |||

The \( \uparrow \) orientations of the moments refer to the c-hexagonal axis while \( \rightarrow \) refer to the \( (a,b) \) planes.

\( ^{a} \) The moments are included in the given incertitude range since their setting to zero does not drastically modify the convergence.

(2 < m < 3.5 \( \mu \) B/Co) and is in good agreement with the KGA rules which predict AF couplings in dimers through Co–O–Co superexchanges [25].

The greater values of local ordered moments in the case of the two oxybridomes (3.42 and \( 3.36 \mu B/Co^{IV} \) ) are probably due to weak Co–O covalence in the absence of the Co–O–Co contact. It is also noteworthy that the refined moments match rather well the effective moments of the several oxyhalides, e.g. both the oxyfluorides and oxybridomes have been assigned LS Co \( ^{III} \) and IS Co \( ^{IV} \) , leading to similar theoretical \( \mu_{eff} \) values.

A variable orbital contribution depending on the local geometry of \( Co^{IV} \) appears as a probable scenario to explain the discrepancies between the local moments of tetrahedral \( Co^{IV} \) for X = F, Cl. Finally, these values are much smaller than in \( BaCoO_{2.8} \) ( \( M_{tetr. Co} = 4.2 \mu B \) ) but once again, in the latter the tetrahedral cobalt are disconnected reducing the covalence effect. Furthermore, in this compound, high local moments are held by each of the \( Co^{III} \) of the linear sub-units avoiding the spin dilution also in the blocks.

4.2. Octahedral oligomers

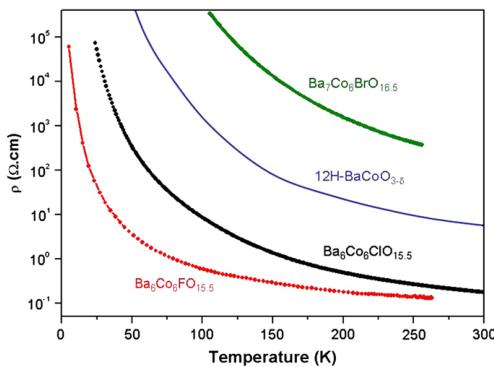

Within the linear tetrameric and trimeric \( Co^{III} \) sub-units, the refined ordered moments appear null or weak relatively in good agreement with the interpretation of the values of the effective moments. Once again, the two oxybridomes display stronger moments \( (0.5-1\;\mu\mathrm{B}/\mathrm{Co}^{\mathrm{III}}) \) probably due to their 2D crystal structures and to the most efficient trapping of electrons in the blocks. This feature is well illustrated by the resistivity of \( Ba_{6}Co_{6}XO_{15.5} \) (X = F, Cl), 12H-BaCoO \( _{3-\delta} \) and \( Ba_{7}Co_{6}BrO_{16.5} \) shown in Fig. 2. The four compounds are semi-conducting while each extra degree of disconnection between blocks leads to an increase of several orders of magnitude of the resistivity. The difference between the fluoride (LS terminal \( Co^{III} \) ) and chloride cases (HS terminal \( Co^{III} \) ) is relevant of more complex phenomena assigned to the effect of anionic chemical pressure in the inter-block space. This

Fig. 2. Comparison of \(\rho\) versus \(T\) as a function of the connectivity between the 2D units.

effect has recently been quantified by magnetic and EPR measurements during the analysis of the \( Ba_{6}Co_{6}(Cl_{1-x}F_{x})O_{15.5} \) solid solution [26].

It also appears that below \( T_{N} \) the local magnetic moments in the oligomers are partially re-organized compared to the models deduced in the paramagnetic region. This point is an additional clue for the trapping of electrons below \( T_{N} \) within these units. The particular propagation of the magnetic couplings in these units has been detailed previously [25]. One should recall that according to the trigonal distortion of the \( t_{2g} \) manifold ( \( 3t_{2g} \rightarrow e_{g}^{\prime} + 2a_{1g} \) ) a magnetic mediation through direct metal–metal transfer ( \( \sigma \) - \( e_{g}^{\prime} \) and \( \pi \) - \( a_{1g} \) overlapping) and the \( \sim90^{\circ} \) M–O–M superexchanges are in competition. As a matter of fact, in the titled compounds, the linear sub-units systematically appear as efficient ferromagnetic connectors while the small fraction of localized moments listed in Table 1 involves deviation from the rigorous LS \( Co^{III} \) model within trimers and tetramers. This is supported by the shorter central \( Co^{III}-O \) distances (1.89 Å) compared to true LS \( Co^{III} \) (1.94 Å) in the \( Co_{3}O_{12} \) trimers of \( Ba_{2}Co_{9}O_{14} \) [10].

4.3. Inter-block magnetic exchanges

In the \( Ba_{6}Co_{6}XO_{15.5} \) and \( Ba_{5}Co_{5}XO_{13} \) compounds, the AF exchanges performed within \( Co_{2}^{IV}O_{7} \) dimers are strongly AF and are by their own responsible for the high negative values of \( \theta_{CW} \) (-278 to -983 K). They are mediated by \( Co^{IV}-O-Co^{IV} \) superexchanges with \( Co-Co \sim 3.5\ \AA \) , \( Co-O \sim 1.8\ \AA \) and \( Co-O-Co \) angles of about \( 155^{\circ} \) . The \( Ba_{5}Co_{5}FO_{13} \) case is particular since the moments are lying in the \( (a,b) \) plane as shown by the strong 00l and 0kl magnetic satellites on ND patterns. It is due to important geometrical modifications in the \( Co_{2}O_{7} \) dimers. In fact compared to the previous values, we now have \( Co-Co = 3.31\ \AA \) , \( Co-O \sim 1.87\ \AA \) and \( Co-O-Co = 125^{\circ} \) and a probable greater in-plane components of the magnetic orbitals.

The disconnection of these blocks in the related oxides leads to Co–O–O–Co super-super exchanges (SSE) at the \( [BaO_{2}]^{2-} \) interface. The geometrical characteristics are: Co–Co \( \sim \) 4.7 Å, Co–O \( \sim \) 1.8 Å, O–O \( \sim \) 3.3 Å, Co–O–O \( \sim \) 85° which yield ferromagnetic paths. However, the moments are mostly lying in the \( (a,b) \) planes with a tilting angle of 63° relative to the c axis [8]. This phenomenon is likely due to the intervention of \( \sigma \) \( O_{2p} \) – \( O_{2p} \) overlapping in-plane.

Finally in the two oxybridomes, an additional Co–Co separation along c is brought by the \( [Ba_{2}O_{2}Br]^{-} \) double layer, Fig. 1e. Once again, the magnetic interaction is mediated by Co–O–O–Co SSEs. The geometrical parameters are: Co–Co \( \sim \) 6.6 Å, Co–O \( \sim \) 1.8 Å, O–O ~ 3.7 Å, Co–O–O \( \sim \) 130°, closer to the linearity of the Co–O–O–Co segments. Our understanding of the ground states of these two systems is far to be completed and appears very complex. In fact, in the two oxybridomes a field-induced spin-flop has been observed and is currently under investigation supporting the strong influence of the inter-block on the properties of these compounds. Therefore, the positive sign of \( \theta_{CW} \) (=55 and 45 K) is relevant of predominant ferromagnetic couplings,

namely the intra-block exchanges despite an antiferromagnetic ground state.

5. Concluding remarks

Similar to the introduction of deficient \( [BaO_{2}] \) for \( [BaO_{3}] \) anionic layers which modifies the 1D \( BaCoO_{3} \) edifice into the 2D 5H- and 12H- \( BaCoO_{3-\delta} \) polytypes, new structural types are obtained from the stacking of \( [BaO_{3}] \) and \( [BaOX] \) (X=F, Cl) layers or \( [Ba_{2}O_{2}Br] \) double layers. The resulting series of cobalt oxyhalides conserve the main characteristics of the parent \( BaCoO_{3-\delta} \) forms, namely the existence of linear sub-units (trimers or tetramers) formed of face-sharing \( Co^{III} \) octahedra decorated with terminal \( Co^{IV} \) tetrahedra. Then, from the structural point of view, the concerned oxides and oxyhalides show identical 2D blocks connected or disconnected depending on the central anionic layer, as follows:

• Ba_{6}Co_{6}XO_{15.5} and Ba_{5}Co_{5}XO_{13} (X=F, Cl): 2D blocks (with tetramers and trimers, respectively) connected by the terminal Co^{IV}O_{4} tetrahedra that share a corner at both sides of the central [BaOX] layer.

• 12H- and 5H-BaCoO_{3-\delta}: isolated 2D blocks (with tetramers and trimers, respectively) with shifted terminal Co^{IV}O_{4} tetrahedra at both sides of the central [BaO_{2}] layer.

• Ba_{7}Co_{6}BrO_{16.5} and Ba_{6}Co_{5}BrO_{14}: isolated 2D blocks (with tetramers and trimers, respectively) and terminal Co^{IV}O_{4} shifted in the \( (a,b) \) plane and along c at both sides of the central \( [Ba_{2}O_{2}Br] \) double layer.

In all the compounds, it appears that the independent 2D blocks remain ferromagnetically ordered, independently of the cobalt mean oxidation state. The terminal \( Co^{IV} \) cations are systematically assigned to IS cobalt, S=3/2. The inter-block exchanges (F, AF or spin-flipped) drastically depend on the connectivity between \( Co^{IV}O_{4} \) tetrahedra (Co–O–Co super-exchanges or Co–O–O–Co SSEs, geometrical features...). It also appears that it controls the orientation of the moments that can lie either along c, or in canted directions. At this point, the role of this connectivity appears of first importance.

References

[1] A. Mendiboure, C. Delmas, P. Hagenmuller, Mater. Res. Bull. 17 (1982) 117.

[2] Y. Kobayashi, T. Mogi, K. Asai, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75 (2006) 104703.

[3] K. Takada, H. Sakurai, E. Takayama-Murimachi, F. Izumi, R.A. Dilanian, T. Sasaki, Nature 422 (2003) 53.

[4] I. Terasaki, Y. Sasago, K. Uchinokura, Phys. Rev. B 56 (1997) R12685.

[5] K. Iwasaki, H. Yamane, S. Kubota, J. Takahashi, M. Shimada, J. Alloys Compd. 358 (2003) 210.

[6] J. Takahashi, H. Yamane, M. Shimada, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 43 (2004) L331.

[7] V. Pardo, P. Blaha, M. Iglesias, K. Schwarz, D. Baldomir, J.E. Arias, Phys. Rev. B 70 (2004) 144422.

[8] K. Boulahya, M. Parras, J.M. Gonzalez-Calbet, U. Amador, J.L. Martinez, V. Tissen, M.T. Fernandez-Diaz, Phys. Rev. B 71 (2005) 144402.

[9] A. Maignan, S. Hébert, D. Pelloquin, V. Pralong, J. Solid State Chem. 179 (2006) 1852.

[10] G. Ehora, S. Daviero-Minaud, M. Colmont, G. André, O. Mentré, Chem. Mater. 19 (2007) 2180.

[11] J. Sun, M. Yang, G. Li, T. Yang, F. Liao, Y. Wang, M. Xiong, J. Lin, Inorg. Chem. 45 (2006) 9151.

[12] K. Yamaura, R.J. Cava, Solid State Commun. 115 (2000) 301.

[13] V. Pardo, J. Rivas, D. Baldomir, M. Iglesias, P. Blaha, K. Schwartz, J.E. Arias, Phys. Rev. B 70 (2004) 212404.

[14] A.J. Jacobson, J.L. Hutchison, J. Solid State Chem. 35 (1980) 334.

[15] M. Parras, A. Varela, H. Seehofer, J.M. Gonzalez-Calbet, J. Solid State Chem. 120 (1995) 327.

[16] K. Boulahya, M. Parras, J. Gonzales-Calbet, J. Mater. Chem. 12 (2000) 25.

[17] V. Eyert, C. Laschinger, T. Kopp, R. Frésard, Chem. Phys. Lett. 385 (2004) 249.

[18] S. Aasland, H. Fjellvag, B. Hauback, Solid State Commun. 101 (1997) 187.

[19] A. Maignan, V. Hardy, S. Hébert, M. Drillon, M.R. Lees, O. Petrenko, D.Mc K. Paul, D. Khomskii, J. Mater. Chem. 14 (2004) 1231.

[20] K. Yamaura, D.P. Young, T. Siegrist, C. Besnard, C. Svensson, Y. Liu, R.J. Cava, J. Solid State Chem. 158 (2001) 175.

[21] N. Tancret, P. Roussel, F. Abraham, J. Solid State Chem. 178 (2005) 3066.

[22] G. Ehora, C. Renard, S. Daviero-Minaud, O. Mentré, Chem. Mater. 19 (2007) 2924.

[23] M. Kauffmann, P. Roussel, Acta Crystallogr. B 63 (2007) 589.

[24] M. Kauffmann, O. Mentré, A. Legris, N. Tancret, F. Abraham, P. Roussel, Chem. Phys. Lett. 432 (2006) 88.

[25] M. Kauffmann, O. Mentré, A. Legris, S. Hébert, A. Pautrat P. Roussel, Chem. Mater., in press.

[26] G. Ehora, M. Kauffmann, S. Daviero-Minaud, P. Roussel, G. Tricot, H. Vezin, O. Mentré, in preparation.