| Transition Temperature | 9 K |

|---|---|

| Experiment Temperature | 1.5 K |

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | Pca21 (#29) |

| Magnetic Space Group | Pc'a21' (#29.101) |

| Magnetic Point Group | m'm2' (7.3.22) |

| Lattice Parameters | 8.5057(2) 8.4931(1) 12.0274(2) 90.00 90.00 90.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1080/00150199708222190 |

| Reference | Y Z.-G., P. Schobinger-Papamantellos, S.-Y. Mao, C. Ritter, E. Suard, M. Sato and H. Schmid, Ferroelectrics (1997) 204 83-95. |

| Label | Element | Mx | My | Mz | |M| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni1 | Ni | 1.65 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.65 |

| Ni2 | Ni | 0.0 | 0.79 | 0.0 | 0.79 |

| Ni3 | Ni | 0.0 | -0.79 | 0.0 | 0.79 |

Title

A neutron diffraction study of the magnetic structure and phase transition in \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite

Authors

Z.-G. Y \( ^{a b} \), P. Schobinger-Papamantellos \( ^{c} \), S.-Y. Mao \( ^{b d} \), C. Ritter \( ^{e} \), E. Suard \( ^{e} \), M. Sato \( ^{a} \) & H. Schmid \( ^{b} \)

\( ^{a} \) Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Niigata University, Niigata, 950-21, Japan \( ^{b} \) Department of Inorganic, Analytical and Applied Chemistry, University of Geneva, CH-1211, Geneva, 4, Switzerland \( ^{c} \) Laboratorium für Kristallographie ETHZ, CH-8092, Zürich, Switzerland \( ^{d} \) Department of Chemistry, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, P. R. China \( ^{e} \) Institut Laue-Langevin, B. P. 156, F-38042, Grenoble, Cedex, 9, France

Materials Studied

\( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite (Ni-Cl boracite). The \( {}^{11}B \)-isotope was used in the crystal synthesis to reduce neutron absorption.

Key Information

- Crystal structure / space group:

- Paramagnetic phase (20 K): Orthorhombic, \( Pca2_{1}1' \) (or \( Pca2_{1} \)). All atoms at sites 4(a).

- Magnetic phase (1.5 K): Nuclear structure remains \( Pca2_{1}1' \). Magnetic space group: \( Pc'a2_{1} \) (or \( Pc'a2_{1}' \)).

- Magnetic ordering type and temperature:

- Antiferromagnetic ordering with weak ferromagnetism below \( T_{N}=9 \) K.

- Second-order magnetic phase transition.

- Coplanar two-dimensionally canted antiferromagnetic arrangement.

- Propagation vector(s): k=0 (magnetic reflections at reciprocal lattice positions of the chemical cell).

- Magnetic moments: (at 1.5 K)

- \( \mu_{1x}=1.65(2)\mu_{B} \) for Ni(1)

- \( \mu_{2y}=-\mu_{3y}=0.79(4)\mu_{B} \) for Ni(2) and Ni(3)

- Total moment for each Ni site is parallel to the orthorhombic a- or b-axis.

- Spin only moment for \( Ni^{2+} \) is \( 2\mu_{B} \).

- Lattice parameters: (at 20 K, \( Pca2_{1} \))

- a = 8.5057(2) Å

- b = 8.4931(1) Å

- c = 12.0274(2) Å

- Any other critical measured values:

- Ni-Ni distances (at 20 K):

- \( d_{Ni(1)-Ni(2)} = 3.8631(1) \) Å

- \( d_{Ni(2)-Ni(3)} = 3.7160(1) \) Å

- \( d_{Ni(3)-Ni(1)} = 3.8069(1) \) Å

- Average \( d_{Ni-Ni} = 4.1269(1) \) Å

- Ni-Cl bond distances (at 20 K):

- Ni(1)-Cl: Long 3.5513(1) Å, Short 2.5093(1) Å

- Ni(2)-Cl: Long 3.4981(1) Å, Short 2.4949(0) Å

- Ni(3)-Cl: Long 3.6112(1) Å, Short 2.4615(0) Å

- Ni-Ni distances (at 20 K):

Synthesis Method

Powder samples (about 12g) were prepared by crushing well-cleaned single crystals of Ni-Cl boracite. These single crystals were grown by chemical vapour transport (CVT). To reduce high neutron absorption, the \( {}^{11}B \)-isotope, in the form of \( {}^{11}B_{2}O_{3} \), was used in the crystal synthesis.

Abstract

The nuclear and magnetic structures and the magnetic phase transition of \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) [Ni-Cl] boracite have been investigated by means of high resolution and high flux neutron powder diffraction between 1.5 and 30 K. The temperature dependence of the magnetic intensities shows an unsharp onset at \( T_{N}=9 \) K, indicating the existence of a second-order magnetic phase transition. Refinements of the magnetic structure give rise to the magnetic space group \( Pc'a2_{1} \) for the magnetic phase below \( T_{N} \), with the magnetic modes \( C_{x} \), \( F_{y} \) and \( A_{z} \) for the three Ni sublattices. The three Ni sites display two kinds of magnetic moment with different values and orientations: Ni(1) has a moment parallel to the main antiferromagnetic axis along \( [100]_{or} \), while Ni(2) and Ni(3) have their antiparallel moments along \( [010]_{or} \)-directions. The total corresponds to a coplanar two-dimensionally canted antiferromagnetic arrangement, which is characteristic for the magnetic structure of Ni-Cl. The refined magnetic moment values at 1.5 K are: \( \mu_{1x}=1.65(2)\mu_{B} \) for Ni(1), and \( \mu_{2y}=-\mu_{3y}=0.79(4)\mu_{B} \) for Ni(2) and Ni(3), respectively, showing a weak magnetic superexchange interaction compared with the spin only moment \( 2\mu_{B}/Ni^{2+} \) observable by neutrons. The magnetic ordering process and the possible frustration effects due to the interwoven configurations between the three Ni sites and the formation of isolated \( Ni_{3}Cl \) groups, are discussed based on the proposed magnetic structure.

Main Content Summary

This paper presents a neutron diffraction study of the nuclear and magnetic structures, and the magnetic phase transition in \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite. Boracites are known multiferroic materials, and Ni-Cl boracite exhibits a sequence of phase transitions, including a ferroelectric/ferroelastic transition at \( T_C=610 \) K and an antiferromagnetic ordering with weak ferromagnetism below \( T_N=9 \) K. The study aims to extend previous investigations on other boracite members to understand the magnetic interaction mechanisms in Ni-Cl.

Powder samples were prepared from \( {}^{11}B \)-enriched single crystals grown by chemical vapour transport. Neutron powder diffraction measurements were conducted between 1.5 K and 30 K at the Saphir reactor and ILL, using D1B and D2B diffractometers. The data were analyzed using the Rietveld-type FULLPROF program, with magnetic structure refinements performed using both full and difference diffractograms to enhance precision, especially given the weak magnetic signals.

The nuclear structure was refined at 20 K (paramagnetic) and 1.5 K (magnetic), confirming an orthorhombic \( Pca2_{1}1' \) space group. Crucially, the nuclear structure showed no significant modification across \( T_N \), indicating a purely magnetic phase transition. The orthorhombic phase exhibits a splitting of Ni sites into three inequivalent positions (Ni(1), Ni(2), Ni(3)) and a degeneration of Ni-Cl distances into "long" and "short" bonds, leading to the formation of isolated triangular \( Ni_3Cl \) pyramids.

At 1.5 K, additional magnetic reflections appeared, consistent with a propagation vector k=0. The magnetic structure was refined to the magnetic space group \( Pc'a2_{1}' \), which is compatible with the observed magnetic point group \( m'm2' \). The refined magnetic structure reveals a dominating antiferromagnetic contribution for Ni(1) with a moment of \( \mu_{1x}=1.65(2)\mu_{B} \) along the \( [100]_{or} \)-direction. Ni(2) and Ni(3) exhibit antiparallel moments of \( \mu_{2y}=-\mu_{3y}=0.79(4)\mu_{B} \) along the \( [010]_{or} \)-direction. This arrangement forms a coplanar two-dimensionally canted antiferromagnetic structure. The observed magnetic moments are notably weaker than the spin-only value of \( 2\mu_{B}/Ni^{2+} \). The temperature dependence of magnetic reflection intensity confirmed a second-order magnetic phase transition at \( T_N=9 \) K.

The paper discusses the magnetic ordering in terms of frustration effects arising from two interwoven configurations. Firstly, Goodenough's rules for superexchange interactions (180° antiferromagnetic, 90° ferromagnetic for \( d^8 \)) lead to frustration in the high-symmetry cubic phase. The structural distortion to the orthorhombic phase, which creates distinct "long" and "short" Ni-Cl bonds, partly lifts this frustration. Secondly, the formation of isolated triangular \( Ni_3-Cl \) pyramids in the ferroelectric orthorhombic phase, with their inherent geometric frustration, also influences the spin ordering. The authors conclude that the 180° antiferromagnetic superexchange dominates, leading to frustrated magnetic moment orientations for cation pairs with a ferromagnetic resultant on most 90° pathways. The observed trend of increasing Néel temperatures from Cl to Br to I boracites supports the role of halogen ions in superexchange interactions.

Conclusion

The magnetic structure model of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite presented in this paper consists essentially in the \( C_{x}(++---) \) mode for Ni(1) with the main antiferromagnetic axis along \( [100]_{or} \)-direction, and the antiferromagnetically coupled \( F_{y}(++++) \) and \( -F_{y}(++++) \) modes for \( \mathrm{Ni}(2) \) and \( \mathrm{Ni}(3) \), respectively. This magnetic structure can be qualitatively understood by the effects of two interwoven configurations responsible for frustration phenomena in the magnetic boracite structures.

The first configuration may be discussed in terms of Goodenough's rules for superexchange interactions. According to these, \( 180^{\circ} \)-transition metal ion \( \leftrightarrow \) anion \( \leftrightarrow \) transition metal ion superexchange is usually strong and leading to antiferromagnetic coupling of the metal ion moments on either side of the anion, whereas \( 90^{\circ} \)-transition metal ion \( \leftrightarrow \) anion \( \Leftrightarrow \) transition metal ion superexchange is tending to ferromagnetic coupling between the metal ion partners for \( d^{8} \) configuration (see Ref. 23). In the cubic boracite structure there exist three-dimensionally linked metal ion octahedra with a halogen in their centre. By inspection of these octahedra we see three mutually perpendicular \( 180^{\circ} \)-superexchange pathways along the three cubic [100]-directions and twelve \( 90^{\circ} \)-pathways lying in cubic (100) planes. Following Goodenough, it can easily be shown that these antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic ordering tendencies cannot be satisfied for all interaction pathways at the same time, i.e. some kind of frustration effect is expected. The frustration effect is well exemplified for Cr-Br and Cr-I boracites, which stay cubic down to at least 4K, and where the frustration even impedes both antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic spin ordering. The broad magnetic susceptibility maximum, which was initially erroneously ascribed to a Néel temperature, \( ^{[5]} \) was in fact due to short range order. In the cubic phase of boracites this frustration is particularly pronounced, because all halogen ion \( \Leftrightarrow \) metal ion bonds are equivalent, i.e. of equal length. Upon the transition from the cubic to the orthorhombic phase (which does not occur in Cr-Br and Cr-I boracites), the equal metal \( \Leftrightarrow \) halogen ion distances of the cubic phase degenerate into “long” and “short” metal \( \Leftrightarrow \) halogen distances (see Tab. II). For Ni-Cl boracite this degeneration partly lifts the frustration, permitting a magnetic phase transition with spin ordering. In Figure 3 the short and long distances for orthorhombic Ni-Cl boracite are represented with full and streaked lines, respectively. As a consequence an alternation “short/long” is found for the \( 180^{\circ} \)-pathways, whereas for the \( 90^{\circ} \)-exchange “short/short”, “long/long” and “short/long” pathways are found.

The second kind of configuration leading to frustration effects is due to the formation of triangular \( Ni_{3}-Cl \) pyramids in the ferroelectric orthorhombic phase with “short” \( Ni \Leftrightarrow Cl \) distances, as stated in Section 3.1. From other antiferromagnetic compounds it is well known that a triangular arrangement of interacting magnetic moment bearing ions is particularly subject to frustration in spin ordering. \( ^{[24,25]} \)

All of these pyramids are isolated from all neighbouring ones by “long” Ni \( \Leftrightarrow \) Cl distances. Therefore one might expect that this “bond breaking” along the \( 180^{\circ} \)-pathways would strongly decrease the strength of the \( 180^{\circ} \)-superexchange. However, it can be seen on Figure 3 that for Ni-Cl boracite the desired antiferromagnetic coupling is satisfied for all three \( 180^{\circ} \)-pathways (e.g. along the \( -\mathrm{Ni}(2)^{2+} \)-Cl \( ^{-} \)-Ni(3) \( ^{2+} \)-chains). Admitting Goodenough's rules, this means that not all of the twelve \( 90^{\circ} \)-pathways are allowed to couple ferromagnetically. In fact, only two pairs couple ferromagnetically ( \( -\mathrm{Ni}(2)^{2+} \)-Cl \( ^{-} \) Ni(2) \( ^{2+} \)- and \( -\mathrm{Ni}(3)^{2+} \)-Cl \( ^{-} \) Ni(3) \( ^{2+} \)-), eight pairs couple with magnetic moments at nearly right angle (e.g. ( \( -\mathrm{Ni}(1)^{2+} \)-Cl \( ^{-} \) Ni(3) \( ^{2+) \) , i.e. with a resultant weak ferromagnetic component as a compromise. We may call the latter interaction “frustrated”. Only two pairs couple antiferromagnetically. The possible magnetic superexchange interactions in Ni-Cl are presented in Table V.

In summary, we have shown that in the magnetic structure of Ni-Cl boracite, the \( 180^{\circ} \)-antiferromagnetic superexchange dominates, leading to “frustrated” magnetic moment orientations of cation pairs with a ferromagnetic resultant on most of the \( 90^{\circ} \)-pathways, whereas the “longer” and “shorter” metal ion \( \Leftrightarrow \) chlorine ion bond lengths seem to play a minor role. The fact that the superexchange passes via the halogen ions in the nickel boracites (and other boracites) is substantiated by the increase of the Néel (Curie) temperatures in the sense Cl (9K) \( \Rightarrow \) Br (30K) \( \Rightarrow \) I (61.5K) for the nickel boracites, reflecting the increase of interaction strength with increasing overlap of the halogen orbitals. However, the magnetic interaction mechanisms in the boracites are probably more complex, because, as discussed in Ref. 13 for Ni-Br boracite, the structure allows possible contributions via other magnetic interaction pathways.

This article was downloaded by: [University of Chicago Library] On: 16 November 2014, At: 19:47 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Ferroelectrics

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gfer20

A neutron diffraction study of the magnetic structure and phase transition in \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite

Z.-G. Y \( ^{a b} \) , P. Schobinger-Papamantellos \( ^{c} \) , S.-Y. Mao \( ^{b d} \) , C. Ritter \( ^{e} \) , E. Suard \( ^{e} \) , M. Sato \( ^{a} \) & H. Schmid \( ^{b} \)

\( ^{a} \) Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Niigata University, Niigata, 950-21, Japan

\( ^{b} \) Department of Inorganic, Analytical and Applied Chemistry, University of Geneva, CH-1211, Geneva, 4, Switzerland

\( ^{c} \) Laboratorium für Kristallographie ETHZ, CH-8092, Zürich, Switzerland

\( ^{d} \) Department of Chemistry, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, P. R. China

\( ^{e} \) Institut Laue-Langevin, B. P. 156, F-38042, Grenoble, Cedex, 9, France

Published online: 26 Oct 2011.

To cite this article: Z.-G. Y, P. Schobinger-Papamantellos, S.-Y. Mao, C. Ritter, E. Suard, M. Sato & H. Schmid (1997) A neutron diffraction study of the magnetic structure and phase transition in \( Ni_{3}^{11} \) B \( _{7} \) O \( _{13} \) Cl boracite, Ferroelectrics, 204:1, 83-95, DOI: 10.1080/00150199708222190

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00150199708222190

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the "Content") contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever.

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

A NEUTRON DIFFRACTION STUDY OF THE MAGNETIC STRUCTURE AND PHASE TRANSITION IN Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl BORACITE

Z.-G. YE \( ^{a,b} \) , P. SCHOBINGER-PAPAMANTELLOS \( ^{c} \) , S.-Y. MAO \( ^{b,d} \) , C. RITTER \( ^{e} \) , E. SUARD \( ^{c} \) , M. SATO \( ^{a} \) and H. SCHMID \( ^{b} \)

\( ^{a} \) Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Niigata University, Niigata 950-21, Japan; \( ^{b} \) Department of Inorganic, Analytical and Applied Chemistry, University of Geneva, CH-1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland; \( ^{c} \) Laboratorium für Kristallographie ETHZ, CH-8092 Zürich, Switzerland; \( ^{d} \) Department of Chemistry, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, P. R. China; \( ^{e} \) Institut Laue-Langevin, B. P. 156, F-38042 Grenoble Cedex 9, France

(Received in final form 15 May 1997)

The nuclear and magnetic structures and the magnetic phase transition of \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) [Ni-Cl] boracite have been investigated by means of high resolution and high flux neutron powder diffraction between 1.5 and 30 K. The temperature dependence of the magnetic intensities shows an unsharp onset at \( T_{N}=9 \) K, indicating the existence of a second-order magnetic phase transition. Refinements of the magnetic structure give rise to the magnetic space group \( Pc'a2_{1} \) for the magnetic phase below \( T_{N} \) , with the magnetic modes \( C_{x} \) , \( F_{y} \) and \( A_{z} \) for the three Ni sublattices. The three Ni sites display two kinds of magnetic moment with different values and orientations: Ni(1) has a moment parallel to the main antiferromagnetic axis along \( [100]_{or} \) , while Ni(2) and Ni(3) have their antiparallel moments along \( [010]_{or} \) -directions. The total corresponds to a coplanar two-dimensionally canted antiferromagnetic arrangement, which is characteristic for the magnetic structure of Ni-Cl. The refined magnetic moment values at 1.5 K are: \( \mu_{1x}=1.65(2)\mu_{B} \) for Ni(1), and \( \mu_{2y}=-\mu_{3y}=0.79(4)\mu_{B} \) for Ni(2) and Ni(3), respectively, showing a weak magnetic superexchange interaction compared with the spin only moment \( 2\mu_{B}/Ni^{2+} \) observable by neutrons. The magnetic ordering process and the possible frustration effects due to the interwoven configurations between the three Ni sites and the formation of isolated \( Ni_{3}Cl \) groups, are discussed based on the proposed magnetic structure.

Keywords: Boracite \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) ; magneto-structural phase transition; magnetic structure; superexchange interaction; frustration; neutron powder diffraction

1. INTRODUCTION

Crystals of the boracite structure family \( M_{3}B_{7}O_{13}X \) (abbreviated M-X), with M standing for divalent metal ions (of Mg, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, or Cd) and X for halogen ions (of Cl, Br, I), are known to undergo a series of ferroelastic/ferroelectric phase transitions. Most of the compounds containing 3d transition metal ions of Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni and Cu, become magnetically ordered at low temperatures, showing a simultaneous presence of ferroelasticity, ferroelectricity and (weak) ferromagnetism, i.e. multiferroic properties. \( ^{[1,2]} \) Nickel-chlorine boracite \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) [Ni-Cl] exhibits the following sequence of phases (in Shubnikov notation), established on the basis of optical, \( ^{[3,4]} \) magnetic, \( ^{[5]} \) magnetoelectric \( ^{[6,7]} \) and crystallographic \( ^{[8,9]} \) characterization:

\[ F\bar{4}3\mathrm{c l}^{\prime}\leftarrow T_{\mathrm{C}}\rightarrow P\mathrm{c a}_{2}{}_{1}{}^{\prime}\leftarrow T_{\mathrm{N}}\rightarrow m^{\prime}m2^{\prime}, \]

with a paramagnetic fully ferroelectric/fully ferroelastic phase below \( T_{C}=610 \) K and an antiferromagnetic ordering with weak ferromagnetism below \( T_{N}=9 \) K. Note that a purely antiferromagnetic mm2 phase was initially proposed to be present between 9 and 25 K, \( ^{[7]} \) but was then discarded on the basis of more precise quasistatic and dynamic measurements of the magnetoelectric coefficients \( \alpha_{23} \) and \( \alpha_{32} \) . \( ^{[6]} \)

The magnetic structures were recently studied for the orthorhombic Co-I, \( [10] \) Co-Br, \( [11] \) Mn-I \( ^{[12]} \) and the orthorhombic/triclinic Ni-Br \( ^{[13]} \) boracites. It is of interest to extend such investigation to the other members of the boracite family in order to compare the magnetic ordering models and to understand the magnetic interaction mechanism in the magnetic boracites. Therefore, the nuclear and magnetic structures of the Ni-Cl boracite at low temperatures have been studied in the present work by means of high resolution neutron powder diffraction, and the magnetic ordering process discussed on the basis of the magnetic structure being proposed.

2. EXPERIMENTAL

Powder samples (of about 12g) were prepared by crushing well cleaned single crystals of Ni-Cl boracite, grown by chemical vapour transport (CVT) \( ^{[14,15]} \) . With a view to reducing the high neutron absorption intensities due to \( {}^{10}B \) of ordinary boron, the \( {}^{11}B \) -isotope in the form of \( {}^{11}B_{2}O_{3} \) was used in the crystal synthesis. For the same purpose, an annular

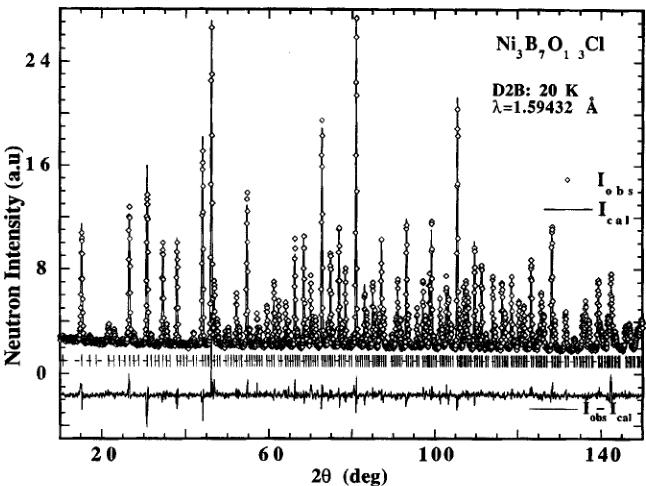

vanadium sample holder was specially fashioned with inner and outer diameter of 10 and 12 mm, respectively. First trials of neutron diffraction measurements were performed by the "DMC" (double axis multicounter diffractometer) and the two-axis spectrometer ( \( \lambda=1.7001 \) Å) at the Saphir reactor in Würenlingen (Switzerland). \( ^{[16]} \) The diffractograms were taken from \( 2\theta=3^{\circ} \) to \( 133^{\circ} \) with a step increment of \( 0.1^{\circ} \) in \( 2\theta \) at 4 K. However, the magnetic neutron diffraction intensities were found to be too weak to allow a reliable refinement of the magnetic structure due to a very weak magnetic ordering moment in Ni-Cl, as can be seen further on. Further neutron powder diffraction measurements were therefore carried out between 1.5 K and 30 K at the ILL (Grenoble, France) both by the "D1B" diffractometer ( \( \lambda=2.52 \) Å) and the high resolution "D2B" diffractometer ( \( \lambda=1.5943 \) Å). The diffractograms were taken from \( 2\theta=10^{\circ} \) to \( 95^{\circ} \) on D1B and \( 2\theta=10^{\circ} \) to \( 150^{\circ} \) on D2B with a step increment of \( 0.1^{\circ} \) and \( 0.05^{\circ} \) in \( 2\theta \) , respectively. The measured data were corrected for absorption, \( ^{[17]} \) and analysed by means of Rietveld-type FULLPROF program, \( ^{[18]} \) using neutron scattering lengths given in Ref. 19 and magnetic form factors from Ref. 20.

The magnetic structure was refined both from full and difference diffractograms, the last ones obtained by subtracting the paramagnetic nuclear data from the data of the low temperature magnetically ordered state.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Nuclear Structure at 20 K and 1.5 K

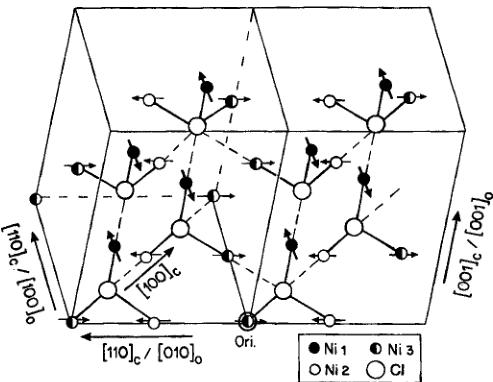

The nuclear structure of Ni-Cl boracite at low temperatures both in the paramagnetic phase and in the antiferromagnetic phase was refined from the high resolution "D2B" neutron data. The number of free parameters was 92. Results are shown in Figure 1 for the paramagnetic phase at 20 K. The space group was found to be \( Pca2_{1}1' \) with all atoms at sites 4(a). The refined structural parameters with the atomic positions and the Debye-Waller thermal factors are given in Table I. The nuclear structure of the magnetic phase below \( T_{N}=9K \) was found to be identical to that of the paramagnetic phase, indicating that the phase transition at \( T_{N} \) (see below) is purely of magnetic origin without significant modification in the nuclear structure. Within three standard deviations, the structural data at low temperatures are in good agreement with those obtained previously for the orthorhombic phase of Ni-Cl from single crystal X-ray diffraction at room temperature \( ^{[8]} \) .

FIGURE 1 Observed, calculated and difference neutron powder diffraction patterns of \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite in the paramagnetic state ( \( Pca2_{1} \) ) at 20 K with nuclear contribution only.

and at low temperatures. \( ^{[9]} \) The high resolution neutron diffraction allowed us to obtain accurate structural parameters at low temperature, which were subsequently used for the full refinement of the nuclear and magnetic structures in the magnetic phase.

In order to understand the magnetic interaction pathways in Ni-Cl boracite, it is worthwhile noting the characteristic structure changes, especially those of the metal ion sites, resulting from the cubic \( F\bar{4}3cl' \) to the orthorhombic \( Pca2_{1}1' \) phase transition at \( T_{C}=610K \) : (i) A splitting of the Ni site into three distinct, inequivalent ones: Ni(1), Ni(2) and Ni(3). Ni(2) and Ni(3), situated on the Ni-Cl-Ni-Cl chains oriented along \( [110]_{or} \) directions (see Fig.3), have a similar chemical environment owing to an approximately parallel shift of both halogens of the \( O_{4}Cl_{2} \) octahedron along a single \( [111]_{c} \) -direction upon the phase transition at \( T_{C} \) . Ni(1), located on the Ni-Cl-Ni-Cl chains parallel to \( [001]_{or} \) , shows a different surrounding with two halogens moving along different \( [111]_{c} \) -directions at an angle of about \( 109^{\circ} \) with each other. (ii) A subsequent splitting up of the Ni-Ni distances, with the largest difference among Ni-Ni distances being found to be 0.5780 (1) Å (at 20 K). (iii) A drastic reduction of the symmetry of the Ni-

TABLE I Refined structural parameters of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite in the paramagnetic state at 20 K ( \( Pca2_{1} \) , all atoms at sites 4(a))

| Atom | x | y | z | B[Å]² |

| Ni1 | 0.75410(74) | 0.2490(22) | 0.2791(7) | 0.16(3) |

| Ni2 | 0.4865(16) | 0.5276(10) | 0.5570(13) | 0.16(3) |

| Ni3 | -0.0188(16) | 0.0349(11) | 0.5563(13) | 0.16(3) |

| Cl | 0.79245(71) | 0.2533(22) | 0.5731(0) | 0.04(9) |

| B1 | 0.5111(20) | 0.4986(18) | 0.3092(19) | 0.17(4) |

| B2 | 0.2562(12) | 0.2462(25) | 0.5525(10) | 0.17(4) |

| B3 | 0.0017(21) | -0.0067(21) | 0.3037(19) | 0.17(4) |

| B4 | 0.4480(11) | 0.2505(24) | 0.4087(11) | 0.17(4) |

| B5 | 0.2479(22) | 0.4013(23) | 0.2236(20) | 0.17(4) |

| B6 | 0.9052(14) | 0.7478(26) | 0.8770(13) | 0.17(4) |

| B7 | 0.7506(23) | 0.8995(23) | 0.7214(19) | 0.17(4) |

| O1 | 0.2283(14) | 0.2537(32) | 0.2938(12) | 0.07(3) |

| O2 | 0.5432(24) | 0.3267(22) | 0.32478(16) | 0.07(3) |

| O3 | 0.3790(22) | 0.3322(18) | 0.4894(16) | 0.07(3) |

| O4 | 0.9576(23) | 0.1592(20) | 0.3230(16) | 0.07(3) |

| O5 | 0.3132(18) | 0.3681(18) | 0.1202(16) | 0.07(3) |

| O6 | 0.1632(23) | 0.9713(20) | 0.2863(15) | 0.07(3) |

| O7 | 0.1286(21) | 0.1693(19) | 0.4804(16) | 0.07(3) |

| O8 | 0.3297(21) | 0.5215(19) | 0.2888(15) | 0.07(3) |

| O9 | 0.1794(18) | 0.1154(17) | 0.1207(14) | 0.07(3) |

| O10 | 0.9508(23) | 0.5884(18) | 0.8999(16) | 0.07(3) |

| O11 | 0.5491(22) | 0.9139(18) | 0.91014(17) | 0.07(3) |

| O12 | 0.9125(23) | 0.5483(17) | 0.7030(16) | 0.07(3) |

| O13 | 0.5904(22) | 0.9349(18) | 0.7044(15) | 0.07(3) |

| a [Å], b[Å], c[Å]: 8.5057(2) 8.4931(1), 12.0274(2) | ||||

| Rg%, R%, Rwp%, χ²: 6.11, 3.94, 13.1, 2.5 | ||||

coordination around Cl, from octahedral to a plane (isosceles triangular) arrangement of the Ni(1), Ni(2) and Ni(3) sites due to a degeneration of the equal Ni ion - Cl ion distance into “long” (e.g. with \( d_{Cl-Ni(3)} = 3.6112(1) \) Å) and “short” (e.g. with \( d_{Cl-Ni(2)} = 2.4949(1) \) Å, at 20 K). The three Ni atoms Ni(1), Ni(2) and Ni(3), with relatively short distances between them: \( d_{Ni(1)-Ni(2)} = 3.8631(1) \) Å, \( d_{Ni(2)-Ni(3)} = 3.7160(1) \) Å and \( d_{Ni(3)-Ni(1)} = 3.8069(1) \) Å if compared with the average Ni-Ni distance \( d_{Ni-Ni} = 4.1269(1) \) Å (at 20 K), therefore form isolated pyramids together with one Cl atom. As stated later on, these structural arrangements play an important role in the magnetic ordering process in Ni-Cl boracite. The metal - halogen atomic distances for the orthorhombic \( Pca2_{1}1' \) phase of Ni-Cl boracite at 20 K are given in Table II.

3.2. Magnetic Ordering at 1.5 K

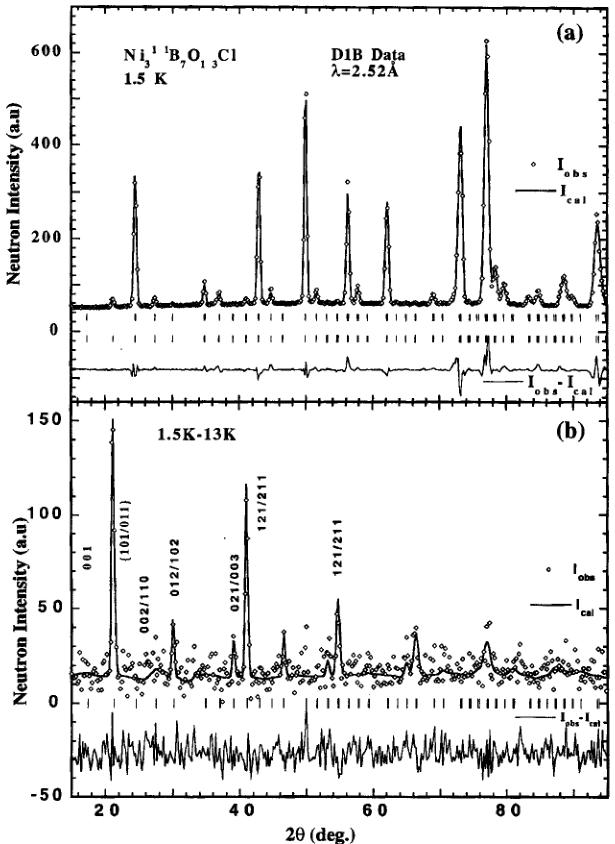

The neutron diffraction pattern at 1.5 K (see Fig. 2) shows several additional reflections of magnetic origin at reciprocal lattice positions of the chemical (nuclear) cell, i.e. k=0, as in the case of the Co-I, Co-Br and Ni-Br

FIGURE 2 Observed, calculated and difference neutron powder patterns of \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite for: (a) full diffractograms at 1.5 K with nuclear and magnetic contributions; (b) difference diffractograms obtained by subtraction of the 13 K nuclear data from the data of the magnetically ordered state at 1.5 K.

boracites. \( ^{[10-13]} \) Since the main magnetic contributions with pseudororthorhombic indices of \( (h0l)/(0kl) \) do not follow the limiting conditions for the possible reflections of the space group \( Pca2_{1}1' \) (0kl, l=2n and h0l,

TABLE II Metal-Halogen Bond Distances in the Orthorhombic phase of Ni-Cl Boracite (20 K)

| Bond | Ni(1)-Cl | Ni(2)-Cl | Ni(3)-Cl |

| “Long” | 3.5513(1) Å | 3.4981(1) Å | 3.6112(1) Å |

| “Short” | 2.5093(1) Å | 2.4949(0) Å | 2.4615(0) Å |

h=2n, n=integer), these reflections can be attributed to an antiferromagnetic ordering. Four magnetic space groups associated with the wave vector character k=0 of the magnetic reflections, are allowed: \( Pca2_{1} \) , \( Pc'a2_{1} \) , \( Pca'2_{1} \) and \( Pc'a'2_{1} \) , but only the space group \( Pc'a2_{1} \) ' is compatible with the magnetic point group \( m'm2' \) deduced from the measurement of the tensor components of the linear magnetoelectric effect \( ^{[6,7]} \) and the observation of the ferromagnetic domains by means of polarized light microscopy. \( ^{[21]} \) This magnetic space group allows a three dimensional canted moment arrangement for the three Ni-sublattices, all at 4(a) sites: x, y, z; -x, -y, \( 1/2+z \) ; \( 1/2+x \) , -y, z and \( 1/2-x \) , y, \( 1/2+z \) . The magnetic symmetry constraint matrix of the magnetic space group \( Pc'a2_{1} \) ' is shown in Table III. The corresponding magnetic modes are \( C_{x}(++--) \) , \( F_{y}(++++) \) and \( A_{z}(+-+) \) . The fact that the \( (10l)/(01l) \) reflections for l=1 and 2 have comparable intensities indicates that the main axis of antiferromagnetism cannot be along the c-direction. The expected weak ferromagnetic contributions (overlapping with the allowed nuclear peaks) are not observed. They are either too weak or their contributions cancel in the structure factor.

3.3. Difference Diagram (1.5 K - 13 K)

Since the observed magnetic reflections are very weak compared with the nuclear ones (Fig. 2a), the refinement of the magnetic structure was performed by using the difference diagram (Fig. 2b) between the magnetically ordered state (at 1.5 K) and the paramagnetic state (at 13 K). This allows a drastic reduction of the number of free parameters and therefore a more precise determination of the magnetic structure model. After testing various possible magnetic structure models with a variety of

TABLE III Symmetry constraint matrix for the magnetic space group \( Pc'a2_{1} \)

\[ \begin{pmatrix}{{{1}}}&{{{1}}}&{{{1}}} \\{{{1}}}&{{{1}}}&{{{-1}}} \\{{{-1}}}&{{{1}}}&{{{-1}}} \\{{{-1}}}&{{{1}}}\end{pmatrix} \]

TABLE IV Refined parameters for the magnetic structure of \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite at 1.5 K, S.G. \( Pc'a2_{1} \) , Magnetic modes \( C_{x}(++--) \) , \( F_{y}(++++) \) and \( A_{x}(+--) \) for the atoms at 4(a) sites: x, y, z; -x, -y, 1/2 + z; 1/2 + x, -y, z and 1/2 - x, y, 1/2 + z.

| Moment | \( \mu_{x}[\mu_{B}] \) | \( \mu_{y}[\mu_{B}] \) | \( \mu_{z}[\mu_{B}] \) | \( \mu_{T}[\mu_{B}] \) |

| Atom | ||||

| Ni (1) | 1.65(2) | 0 | 0 | 1.65(2) |

| Ni (2) | 0 | 0.79(4) | 0 | 0.79(4) |

| Ni (3) | 0 | -0.79(4) | 0 | -0.79(4) |

| \( R_{m}=24\%, R_{wp}=35\%, \chi^{2}=1.12 \) | ||||

magnetic moment directions in the magnetic space group \( Pc'a2_{1} \) , the best model was found with the parameters given in Table IV. The refinement results are shown in Figure 2b. Although such a refinement usually results in higher reliability values ( \( R_{m}=24\% \) , \( R_{wp}=35\% \) , \( R_{ep}=26\% \) ) due to the larger errors on the background estimation, the errors on the ordered moment values are much smaller than those obtained from a refinement of all parameters of the entire pattern with essentially lower R-factors. This model indicates that Ni(2) and Ni(3) have opposite magnetic moments along the b-axis and that no antiferromagnetic contribution is present along the c-axis, as is consistent with the above observation of the magnetic reflection peaks. The total moment for each Ni site is parallel to the orthorhombic a- or b-axis. Figure 2a displays the refined nuclear and magnetic phases for space group \( Pc'a2_{1} \) at 1.5 K.

3.4. Magnetic Structure

The proposed (three dimensional) magnetic structure is represented in Figure 3. It is characterized by a dominating antiferromagnetic contribution of the mode \( C_{x} \) for the Ni(1) site only, with the uniaxial magnetic moment arrangement in the \( [100]_{or} \) -direction. The Ni(2) and Ni(3) sites adopt the magnetic modes \( F_{y} \) and \( -F_{y} \) , respectively. Their magnetic moments are ferromagnetically ordered along the \( [010] \) -pseudo-orthorhombic direction but antiferromagnetically coupled with each other. The magnetic structure of Ni-Cl boracite corresponds in reality to a two-dimensionally canted arrangement of the three Ni sites with \( a_{or} \) or \( [100]_{or} \) as the main axis of antiferromagnetism. The ordered magnetic moments at 1.5 K are refined to be: \( \mu_{1x}=1.65(2) \) \( \mu_{B} \) for Ni(1), \( \mu_{2y}=-\mu_{3y}=0.79(4) \) \( \mu_{B} \) for Ni(2) and Ni(3), respectively. The ordered moment values of Ni-Cl boracite lie below the spin only value of the nickel ions 2S \( \mu_{B} \) , i.e. \( 2\mu_{B}/Ni^{2+} \) , observable by neutrons. Note that in the Ni-Br boracite \( Ni_{3}Br_{7}O_{13}Br \) the ordered magnetic moment was found to be larger than that value (3.56(5) \( \mu_{B} \) for Ni(1)). Such weak

FIGURE 3 Magnetic structure of \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite at 1.5 K represented in the orthorhombic coordinate system, space group \( Pc^{a}2_{1} \) . The small solid, open and half-solid circles denote \( \mathrm{Ni}(1) \) , \( \mathrm{Ni}(2) \) and \( \mathrm{Ni}(3) \) ions, respectively. The large open circles stand for Cl ions. The arrows indicate the magnetic moment components of nickel ions. Only Cl and Ni atoms with their respective spin directions are shown.

moments explain the very weak intensities of the magnetic reflections observed for Ni-Cl.

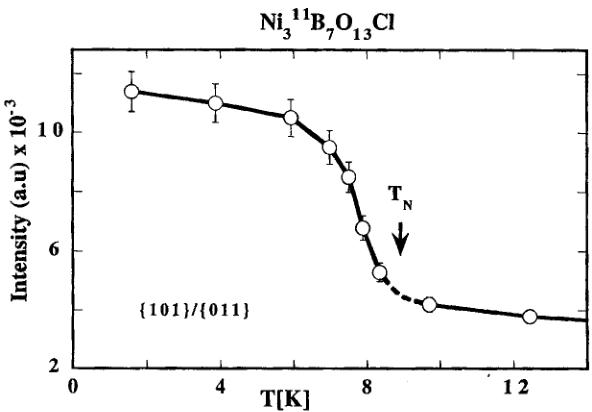

3.5. Magnetic Phase Transition

Figure 4 gives the temperature dependence of the integrated neutron intensity for the strongest magnetic orthorhombic reflection \( \{101\}/\{011\} \) measured by the “DMC” diffractometer. The intensity decreases gradually with increasing temperature and shows an inflection point around \( T_{N}=9~K \) , indicating the second order character for the magnetic phase transition, in agreement with the previous magnetic and magnetoelectric characterization. \( ^{[5-7]} \) The residual tail of the magnetic reflection intensity above \( T_{N} \) results from a relatively low single-to-noise ratio obtained from “DMC” due to the weak magnetic moments.

4. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The magnetic structure model of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite presented in this paper consists essentially in the \( C_{x}(++---) \) mode for Ni(1) with the main

FIGURE 4 Temperature dependence of the integrated intensity of the magnetic orthorhombic \( \{101\}/\{011\} \) neutron reflection of \( Ni_{3}^{11}B_{7}O_{13}Cl \) boracite.

antiferromagnetic axis along \( [100]_{or} \) -direction, and the antiferromagnetically coupled \( F_{y}(++++) \) and \( -F_{y}(++++) \) modes for \( \mathrm{Ni}(2) \) and \( \mathrm{Ni}(3) \) , respectively. This magnetic structure can be qualitatively understood by the effects of two interwoven configurations responsible for frustration phenomena in the magnetic boracite structures.

The first configuration may be discussed in terms of Goodenough's rules for superexchange interactions. \( ^{[22-23]} \) According to these, \( 180^{\circ} \) -transition metal ion \( \leftrightarrow \) anion \( \leftrightarrow \) transition metal ion superexchange is usually strong and leading to antiferromagnetic coupling of the metal ion moments on either side of the anion, whereas \( 90^{\circ} \) -transition metal ion \( \leftrightarrow \) anion \( \Leftrightarrow \) transition metal ion superexchange is tending to ferromagnetic coupling between the metal ion partners for \( d^{8} \) configuration (see Ref. 23). In the cubic boracite structure there exist three-dimensionally linked metal ion octahedra with a halogen in their centre. By inspection of these octahedra we see three mutually perpendicular \( 180^{\circ} \) -superexchange pathways along the three cubic [100]-directions and twelve \( 90^{\circ} \) -pathways lying in cubic (100) planes. Following Goodenough, it can easily be shown that these antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic ordering tendencies cannot be satisfied for all interaction pathways at the same time, i.e. some kind of frustration effect is expected. The frustration effect is well exemplified for Cr-Br and Cr-

I boracites, which stay cubic down to at least 4K, and where the frustration even impedes both antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic spin ordering. The broad magnetic susceptibility maximum, which was initially erroneously ascribed to a Néel temperature, \( ^{[5]} \) was in fact due to short range order. In the cubic phase of boracites this frustration is particularly pronounced, because all halogen ion \( \Leftrightarrow \) metal ion bonds are equivalent, i.e. of equal length. Upon the transition from the cubic to the orthorhombic phase (which does not occur in Cr-Br and Cr-I boracites), the equal metal \( \Leftrightarrow \) halogen ion distances of the cubic phase degenerate into “long” and “short” metal \( \Leftrightarrow \) halogen distances (see Tab. II). For Ni-Cl boracite this degeneration partly lifts the frustration, permitting a magnetic phase transition with spin ordering. In Figure 3 the short and long distances for orthorhombic Ni-Cl boracite are represented with full and streaked lines, respectively. As a consequence an alternation “short/long” is found for the \( 180^{\circ} \) -pathways, whereas for the \( 90^{\circ} \) -exchange “short/short”, “long/long” and “short/long” pathways are found.

The second kind of configuration leading to frustration effects is due to the formation of triangular \( Ni_{3}-Cl \) pyramids in the ferroelectric orthorhombic phase with “short” \( Ni \Leftrightarrow Cl \) distances, as stated in Section 3.1. From other antiferromagnetic compounds it is well known that a triangular arrangement of interacting magnetic moment bearing ions is particularly subject to frustration in spin ordering. \( ^{[24,25]} \)

All of these pyramids are isolated from all neighbouring ones by “long” Ni \( \Leftrightarrow \) Cl distances. Therefore one might expect that this “bond breaking” along the \( 180^{\circ} \) -pathways would strongly decrease the strength of the \( 180^{\circ} \) -superexchange. However, it can be seen on Figure 3 that for Ni-Cl boracite the desired antiferromagnetic coupling is satisfied for all three \( 180^{\circ} \) -pathways (e.g. along the \( -\mathrm{Ni}(2)^{2+} \) -Cl \( ^{-} \) -Ni(3) \( ^{2+} \) -chains). Admitting Goodenough's rules, this means that not all of the twelve \( 90^{\circ} \) -pathways are allowed to couple ferromagnetically. In fact, only two pairs couple ferromagnetically ( \( -\mathrm{Ni}(2)^{2+} \) -Cl \( ^{-} \) Ni(2) \( ^{2+} \) - and \( -\mathrm{Ni}(3)^{2+} \) -Cl \( ^{-} \) Ni(3) \( ^{2+} \) -), eight pairs couple with magnetic moments at nearly right angle (e.g. ( \( -\mathrm{Ni}(1)^{2+} \) -Cl \( ^{-} \) Ni(3) \( ^{2+) \) , i.e. with a resultant weak ferromagnetic component as a compromise. We may call the latter interaction “frustrated”. Only two pairs couple antiferromagnetically. The possible magnetic superexchange interactions in Ni-Cl are presented in Table V.

In summary, we have shown that in the magnetic structure of Ni-Cl boracite, the \( 180^{\circ} \) -antiferromagnetic superexchange dominates, leading to “frustrated” magnetic moment orientations of cation pairs with a ferromagnetic resultant on most of the \( 90^{\circ} \) -pathways, whereas the “longer”

TABLE V Superexchange Interaction Net in Ni-Cl Boracite

| Type of -Ni-Cl-Ni-Superexchange | Number of -Ni-Cl-Ni-pathways | -Ni-Cl-Ni-bond lengths* | Order type on -Ni-Cl-Ni-pathway | Orientation of pathways; indices: pseudo-cubic | orthorhomb. |

| 180° | 3 | short-long | 3 × AFM. | along [100]c | along [110]or |

| along [010]c | along [110]or | ||||

| along [001]c | along [001]or | ||||

| 90° | 3 | short-short | 1 × AFM. | in (001)c | in (001)or |

| in (100)c | in (110)or | ||||

| in (010)c | in (110)or | ||||

| 90° | 6 | long-long | 1 × AFM. | in (001)c | in (001)or |

| in (100)c | |||||

| in (110)c | |||||

| 90° | 6. | short-long | 2 × FERROM. | in (001)c | in (001)or. |

| in (100)c | |||||

| in (110)c |

*) For example, “short-long” stands for Ni ⇔ Cl short, Cl ⇔ Ni long bond

[on Figure 3: full lines = short, broken lines = long]

Total of pathways: \( 3 \times 180^{\circ} \) (AFM.)

12 × 90° (2 × AFM. + 2 × FERROM. + 8 × FRUSTR.)

and “shorter” metal ion \( \Leftrightarrow \) chlorine ion bond lengths seem to play a minor role. The fact that the superexchange passes via the halogen ions in the nickel boracites (and other boracites) is substantiated by the increase of the Néel (Curie) temperatures in the sense Cl (9K) \( \Rightarrow \) Br (30K) \( \Rightarrow \) I (61.5K) for the nickel boracites, reflecting the increase of interaction strength with increasing overlap of the halogen orbitals. However, the magnetic interaction mechanisms in the boracites are probably more complex, because, as discussed in Ref. 13 for Ni-Br boracite, the structure allows possible contributions via other magnetic interaction pathways.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to R. Cros and R. Boutellier for technical help. This work was partly supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

References

[1] Schmid, H. (1994). Ferroelectrics, 162, 317.

[2] Tolédano, P., Schmid, H., Clin, M. and Rivera, J.-P. (1985). Phys. Rev. B, 32, 6006.

[3] Schmid, H. and Tippmann, H. (1978). Ferroelectrics, 20, 21.

[4] Haida, M., Kohn, K. and Schmid, H. (1974). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn., 37, 1463.

[5] Quézel, G. and Schmid, H. (1968). Solid State Commun., 6, 447.

[6] Rivera, J.-P. and Schmid, H. (1991). J. Appl. Phys., 70, 6410.

[7] Rivera, J.-P., Schmid, H., Moret, J. M. and Bill, H. (1974). Int. J. Magnetism., 6, 211.

[8] Kubel, F., Mao, S.-Y. and Schmid, H. (1992). Act. Cryst., C48, 1167.

[9] Mao, S.-Y. (1993). Thesis N° 2602, University of Geneva, Switzerland.

[10] Clin, M., Schmid, H., Schobinger, P. and Fischer, P. (1991). Phase Transitions, 33, 149.

[11] Schobinger-Papamantellos, P., Fischer, P., Kubel, F. and Schmid, H. (1994). Ferroelectrics, 162, 93.

[12] Crotaz, O., Schobinger-Papamantellos, P., Suard, E., Ritter, C., Gentil, S., Rivera, J.-P. and Schmid, H. (1997). Ferroelectrics (at press).

[13] Mao, S. Y., Kubel, F., Schmid, H., Schobinger, P. and Fischer, P. (1993). Ferroelectrics, 146, 81.

[14] Schmid, H. (1965). J. Phys. Chem. Solids, 26, 973.

[15] Schmid, H. and Tippmann, H. (1979). J. Crystal Growth, 46, 723.

[16] Schefer, J., Fischer, P., Heer, H., Isacson, A., Koch, M. and Thut, R. (1990). Instr. Meth., A288, 477.

[17] Paalman, H. M. and Pings, C. G. (1962). J. Appl. Phys., 33, 2635.

[18] Rodríguez-Carvajal, J. (1993). Physica B, 192, 55.

[19] Sears, V. F. (1992). Neutron News, 3, 26.

[20] Brown, P. J. (1993). International Tables for Crystallography (Ed. By Wilson, A. J. C.) Vol. C, Table 4.4.4, Kluwer, Dordrecht.

[21] Brunskill, I. H. and Schmid, H. (1981). Ferroelectrics, 36, 395.

[22] Goodenough, J. B. (1960). J. Appl. Phys., 31S, 359.

[23] Goodenough, J. B. (1963). “Magnetism and Chemical Bond”, Wiley, New York, pp. 165–185 and Figure 43 p. 181.

[24] Lacorre, P., Leblanc, M., Pannetier, J. and Ferey, G. (1991). J. Magn. Magn. Mat., 94, 337.

[25] Reimers, J. N., Dahn, J. R., Greedan, J. E., Stager, C. V., Liu, G., Davidson, I. and von Sacken, U. (1993). J. Solid State Chem., 102, 542.