| Transition Temperature | 30 K |

|---|---|

| Experiment Temperature | 8 K |

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | Pca21 (#29) |

| Magnetic Space Group | Pc'a21' (#29.101) |

| Magnetic Point Group | m'm2' (7.3.22) |

| Lattice Parameters | 8.51600 8.49500 12.03400 90.00 90.00 90.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1080/00150199308008529 |

| Reference | S.Y. Mao, F. Kubel, H. Schmid, P. Schobinger and P. Fischer, Ferroelectrics (1993) 146 81-97. |

| Label | Element | Mx | My | Mz | |M| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni1 | Ni | 3.51 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 3.56 |

| Ni2 | Ni | 0.0 | 1.31 | 0.2 | 1.33 |

| Ni3 | Ni | 0.0 | -1.31 | -0.5 | 1.40 |

MAGNETIC STRUCTURES AND PHASE TRANSITIONS OF NICKEL-BROMINE BORACITE Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br. A NEUTRON POWDER DIFFRACTION STUDY

S. Y. MAO, F. KUBEL and H. SCHMID

Département de Chimie Minérale, Analytique et Appliquée, Université de Genève, CH-1211 Genève 4, Switzerland

and

P. SCHOBINGER Institut für Kristallographie und Petrographie ETHZ, CH-8092 Zürich, Switzerland

and

P. FISCHER Labor für Neutronenstreuung ETHZ, PSI CH-5232 Villigen [PSI], Switzerland

(Received July 16, 1993)

The nuclear crystal structure and the magnetic ordering of the two ferroelectric/weakly ferromagnetic phases of Nickel-Bromine boracite with the Shubnikov groups of \( Pc^{\prime}a2_{1}^{\prime} \) (30–21K) and P1 (below 21K)—postulated previously on the basis of magnetoelectric and optical data—have been investigated by neutron powder diffraction. The neutron spectra confirm the onset of magnetic ordering at 30 K but do not resolve the transition to the triclinic symmetry. The observed neutron intensities of the orthorhombic and triclinic phase, collected at 24 K and 8 K, respectively, have been interpreted in terms of the magnetic space group \( Pc^{\prime}a2_{1}^{\prime} \) by an essentially antiferromagnetic ordering of the nickel ion moments. The magnetic structure refinements allowed to distinguish two different types of the magnetically ordered nickel ions among the three inequivalent nickel sites. Two possible magnetic structure models and a potential frustration phenomenon during spin ordering are discussed.

Keywords: boracite, neutron diffraction, magnetic structure, ferroelectric, ferromagnetic, ferroelastic

1. INTRODUCTION

Nickel-Bromine boracite with the chemical formula \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) , abbreviated henceforth Ni—Br, is a member of the boracite structural family \( M_{3}B_{7}O_{13}X \) , where M denotes a divalent transition metal ion and X a halogen ion. At \( \sim398~K \) , Ni—Br undergoes an improper structural first order transition from a paramagnetic cubic high temperature phase, space group \( F\bar{4}3c1' \) with 8 formula units per unit cell, to a paramagnetic fully ferroelectric/fully ferroclastic orthorhombic phase with space group \( Pca2_{1}1' \) and 4 formula units per unit cell. This transition was studied by measurements of dielectric permittivity, \( ^{1-3} \) spontaneous polarization, \( ^{3} \) and spon-

taneous birefringence. \( ^{4-6} \) The crystal structure of the orthorhombic phase at \( T = 293~K \) has been refined by X-ray diffraction on a ferroelectric/ferroelastic single domain crystal. \( ^{7} \) The primitive unit cell volume of orthorhombic Ni—Br boracite doubles at the cubic-to-orthorhombic phase transition with the orientation of \( a_{0} // [\bar{1}10] \) -cubic, \( b_{0} // [110] \) -cubic and \( c_{0} // [001] \) -cubic, where \( a_{0} \) , \( b_{0} \) , \( c_{0} \) denote the orthorhombic axes. The nuclear structure of this phase is stable down to 21 K.

The Ni—Br boracite undergoes a second order spin ordering transition \( T_{c1} \sim 29 \) K to a weakly ferromagnetic phase with the spontaneous magnetization vector along the \( b_{0} \) -axis, hence of magnetic point group \( m'm^{2} \) . At \( T_{c1} = 21 \) K a transition takes place to another magnetic phase with triclinic magnetic point group 1. These phase transitions and the point groups of the two magnetic phases were established by combining information from magnetoelectric effect, \( ^{3} \) magnetic birefringence, \( ^{8} \) Faraday rotation and polarized light microscopy of structural and magnetic domains. \( ^{6,8-10} \) More recently the triclinic ferroelectric/ferromagnetic phase with point group 1 was postulated on the basis of new types of domain walls, which are characteristic of triclinic symmetry, and of components of spontaneous Faraday rotation observed along all three pseudo-orthorhombic principal axes \( a_{0} \) , \( b_{0} \) and \( c_{0} \) . \( ^{8-10} \)

Using an orthorhombic ferroelectric/ferroelastic single domain crystal, the triclinic symmetry below 21 K has recently been corroborated by the measurement of components of the spontaneous magnetization vector along all three pseudorthorhombic axes \( a_{0} \) , \( b_{0} \) and $ c_{0}\

On the basis of symmetry considerations, \( ^{12} \) of the orientation of the spontaneous magnetization vector \( ^{11} \) and the space group \( Pca2_{1}1' \) , established earlier by X-ray single crystal diffraction, \( ^{7} \) it became clear that the only possible magnetic space group of the weakly ferromagnetic phase between 21 K and 29 K must be \( Pc'a2_{1}' \) and P1 for the ferromagnetic phase below 21 K. \( ^{11,13} \)

One of the prerequisites for understanding the physical properties of the simultaneously ferroelectric, ferroelastic and “weakly” ferromagnetic boracite crystals is the knowledge of the spin arrangements described in terms of the magnetic space group. For solving the magnetic structures in a straightforward manner, neutron diffraction on a large (at least a few mm \( ^{3} \) ) ferroelectric/ferroelastic single domain crystal would be adequate. However, up to now, such large ferroelastic single domains cannot be prepared. There are different reasons for that: 1) Because of too large electric poling field strength it is impossible to obtain ferroelectric/ferroelastic single domains large enough for neutron diffraction, but only very thin platelets. 2) Due to the ferroelectric/ferroelastic and magnetic phase transitions, the single crystals always use to be highly twinned, usually with a non-equi-weight distribution of the domain states. That is why no valuable investigation of the magnetic structure of boracites was so far accomplished using single crystal neutron diffraction.

Even a single monodomain out of the six possible ferroelastic/ferroelectric ones of orthorhombic Ni—Br boracite may develop up to eight domain states in the triclinic phase of symmetry 1, i.e., four ferroelastic domains, each of which with

up to two ferromagnetic non-ferroelastic subdomains. For the entire single crystal the total number of possible domain states in the triclinic phase is 48! However, there is usually a non-equi-weight distribution of them which may lead to an apparent lower symmetry as was the case in the magnetic structure determination of Ni—I boracite \( ^{15} \) performed on a big single crystal with a “supposed-to-be” electrically and magnetically poled state, which mimicked the triclinic magnetic space group P1 instead of yielding the correct monoclinic point symmetry m' determined later by means of combined polarized light microscopy, birefringence and dielectric studies. \( ^{3} \)

Therefore with a view to confirming the magnetic phase transitions and to establishing the magnetic moment vectors in the “weakly” ferromagnetic low temperature phases of Ni—Br boracite, systematic X-ray and neutron powder diffraction studies both of the nuclear structure and of the magnetic structures were undertaken in this work.

2. EXPERIMENTAL AND REFINEMENT

2.1 Sample Preparation

The crystals of Ni—Br boracite were synthesized by chemical vapor transport. \( ^{[16]} \) In order to reduce the high neutron absorption intensities due to \( {}^{10}B \) of ordinary boron, the \( {}^{11}B \) -isotope was used in the form of \( {}^{11}B_{2}O_{3} \) in the crystal synthesis. The powder sample was obtained by crushing small single crystals.

2.2 Neutron Powder Diffraction

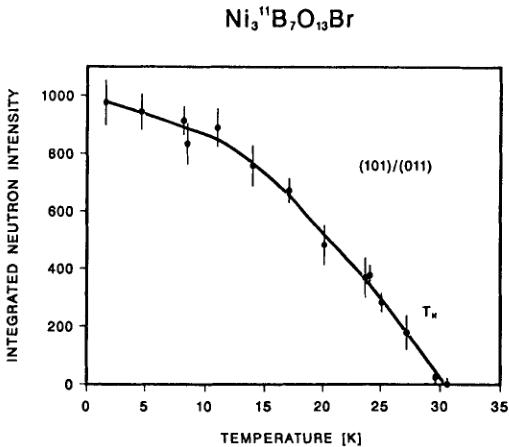

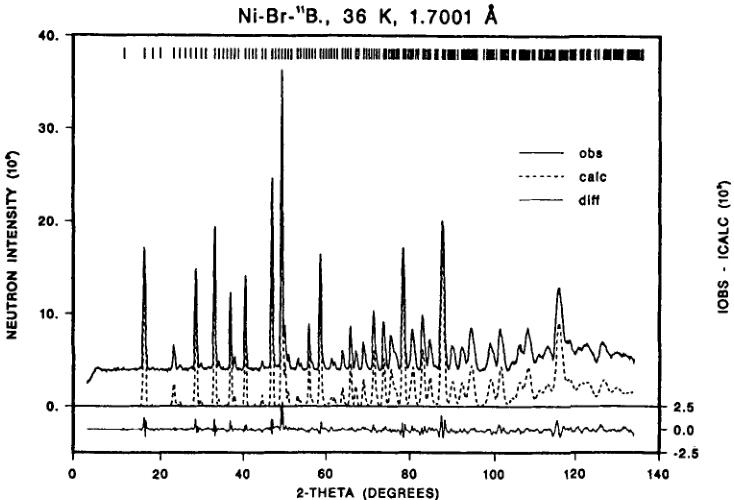

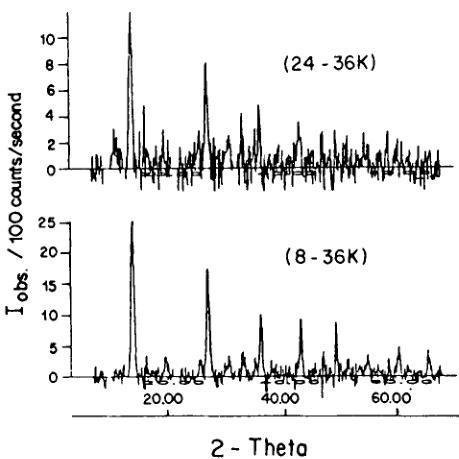

The neutron diffraction measurements were performed on the “DMC” (double axis multicounter system) \( ^{17} \) at the Saphir reactor in Würrelingen ( \( \lambda = 1.7001 \AA \) ). Three neutron diffractograms were taken from \( 2\theta = 3^{\circ} \) to \( 133^{\circ} \) with a step increment of \( 0.1^{\circ} \) in \( 2\theta \) at 8, 24 and 36 K. The magnetic pseudo-orthorhombic (101/011) reflection was followed (Figure 1) in the temperature range of 8–40 K. In order to avoid high absorption, in spite of using the \( {}^{11}B \) isotope, a tubular vanadium sample holder of wall thickness 2.0 mm and outer diameter 12 mm was used. With a view to analysing the expected weak magnetic moments, the high intensity instrumental configuration (without primary collimation) was used.

The data were corrected for absorption \( ^{18} \) and evaluated by the line profile analysis method. \( ^{19-21} \) The scattering lengths and magnetic form factors are taken from V. Sears \( ^{22} \) in Methods of Experimental Physics and from Watson and Freeman, \( ^{23} \) respectively.

2.3 X-Ray Powder Diffraction and Refinement

The X-ray powder diffraction was realized on a high-resolution HUBER powder diffractometer with GUINIER geometry (Ge monochromator, \( \lambda(\mathrm{CuK}\alpha_{1}) = 1.54056 \) Å) at \( T = 36 \, K \) , 23 K, 10 K and 8 K. High-precision unit cell parameters were obtained by using silicon powder (a = 5.429774 Å, \( T = 40 \, K \) ) as a standard. The

FIGURE 1 Integrated intensity of the magnetic (pseudo)-orthorhombic (101)/(011) neutron reflection of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) boracite as a function of temperature. \( T_{c1} \approx 30 \) K indicates the first magnetic phase transition temperature.

step scans were taken from \( \theta = 5^{\circ} \) to \( \theta = 50^{\circ} \) with increments of \( \theta = 0.005^{\circ} \) and a counting time of 20s per step. The refinement was performed with a modified program from DBW32.S. \( ^{24} \) The measurement for structure refinement at 10 K was carried out under the same conditions but with a longer counting time of 30s per step. Two sets of atomic position parameters were refined. The first refinement used a diffraction profile containing Si as an internal standard at T = 36 K with a total of 74 variables: zeropoint, \( 2 \times 1 \) scale factors (Ni—Br and Si), \( 2 \times 3 \) halfwidth parameters, \( 2 \times 1 \) pseudo-Voigt profile parameters, \( 2 \times 1 \) asymmetry parameters, \( 2 \times 1 \) preferred orientation parameters, four cell parameters ( \( 3 + 1 \) ), five isotropic displacement parameters [Ni(1), Ni(2), Ni(3), Br and Si] and 50 atomic positional parameters for Ni, Br and O atoms. The other refinement was carried out on a spectrum measured at T = 10 K without Si contribution, and with 26 refined variables. The background was manually corrected with 21 points.

The bond distances and bond angles were calculated by using the BONDLA program in the XTAL 3.0 system. \( ^{25} \)

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Nuclear Structure at 36 and 8 K

The refinement results of the neutron powder diffraction of the paramagnetic phase at 36 K are summarized in Table I and Figure 2. Both the neutron diffraction and the X-ray diffraction studies from room temperature to low temperature showed no significant structural phase transition down to 8 K. This can be directly seen

TABLE I

Refined atomic parameters from the 36 K neutron data (paramagnetic phase, space group \( Pca2_{1}1' \) ) of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) boracite

| Atom | x | y | z | B(Å−2) |

| Ni(1) | 0.744(4) | 0.249(6) | 0.730(3) | 0.5(1) |

| Ni(2) | 0.088(4) | 0.475(3) | 0.501(5) | 0.5(1) |

| Ni(3) | 0.985(4) | 0.024(3) | 0.502(5) | 0.5(1) |

| Br | 0.773(4) | 0.251(1) | 0.51176 | 1.4(4) |

| B(1) | 0.494(6) | 0.483(5) | 0.745(5) | 0.2(1) |

| B(2) | 0.253(3) | 0.252(8) | 0.497(4) | 0.2(1) |

| B(3) | 0.094(7) | -0.005(6) | 0.745(6) | 0.2(1) |

| B(4) | 0.046(3) | 0.264(4) | 0.851(4) | 0.2(1) |

| B(5) | 0.753(6) | 0.593(6) | 0.672(5) | 0.2(1) |

| B(6) | 0.396(4) | 0.251(7) | 0.831(5) | 0.2(1) |

| B(7) | 0.758(6) | -0.091(5) | 0.672(5) | 0.2(1) | O(1) | 0.753(5) | 0.751(8) | 0.739(4) | 0.0# |

| O(2) | 0.956(5) | 0.325(6) | 0.785(6) | 0.0# |

| O(3) | 0.883(7) | 0.673(7) | 0.441(5) | 0.0# |

| O(4) | 0.531(5) | 0.173(5) | 0.780(6) | 0.0# |

| O(5) | 0.682(5) | 0.640(6) | 0.580(5) | 0.0# |

| O(6) | 0.834(6) | 0.027(7) | 0.737(6) | 0.0# |

| O(7) | 0.139(6) | 0.178(6) | 0.438(6) | 0.0# |

| O(8) | 0.659(6) | 0.474(6) | 0.733(5) | 0.0# |

| O(9) | 0.821(6) | -0.123(6) | 0.575(6) | 0.0# |

| O(10) | 0.434(4) | 0.413(5) | 0.840(5) | 0.0# |

| O(11) | 0.047(5) | 0.079(4) | 0.854(5) | 0.0# |

| O(12) | 0.914(5) | 0.557(6) | 0.657(7) | 0.0# |

| O(13) | 0.572(5) | -0.058(5) | 0.656(5) | 0.0# |

| R-FACTORS | Axes (Å) | |||

| Rn=3.28%, Rw=7.97% | 8.516(2) | |||

| RB=8.19% | 8.495(2) | |||

| Rxp=3.07% | 12.034(3) | |||

| x²=7.12 | V=870.6(1)ų | |||

| Z=4 |

: non refined

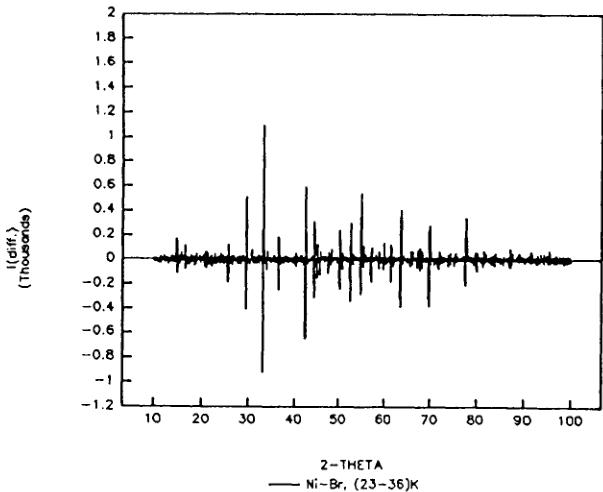

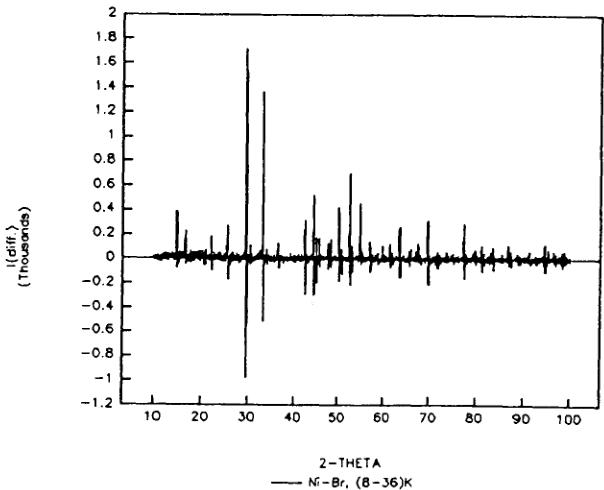

from the X-ray difference diagrams (23–36) K and (8–23) K (Figure 3). The former providing the information on structural changes related to the first magnetic transition at \( T_{c1} = 29 \) K (without symmetry reduction), while the latter refers to the second magnetic phase transition at \( T_{c2} = 21 \) K, which is related to a symmetry reduction from orthorhombic to triclinic. The presented data display a negligible deviation from the statistical average.

The calculated bond distances (based on the cell parameters refined from X-ray powder diffraction with Si as an internal standard at 36 K) around the Ni atoms and bond angles around the Br atom at 36 K and 10 K are listed in Table II and compared with X-ray single crystal data at 293 K. \( ^{7} \) No significant differences between three data sets (neutron diffraction of Ni—Br at 36 K; X-ray diffraction of Ni—Br + Si at 36 K; X-ray diffraction at 10 K) are found from the bond distances around the Ni atoms. However, the isotropic displacement parameter of Ni(1) refined from X-ray powder diffraction at T = 10 K significantly differs from those of Ni(2) and Ni(3) (Table III). The anisotropy displacement parameters of Ni(1) also differ from those of Ni(2) and Ni(3) as found for other orthorhombic boracites at room temperature. \( ^{7,26-29} \) Some previous Mössbauer studies of orthorhombic iron boracites also showed two different types of metal ion site. \( ^{28,29} \)

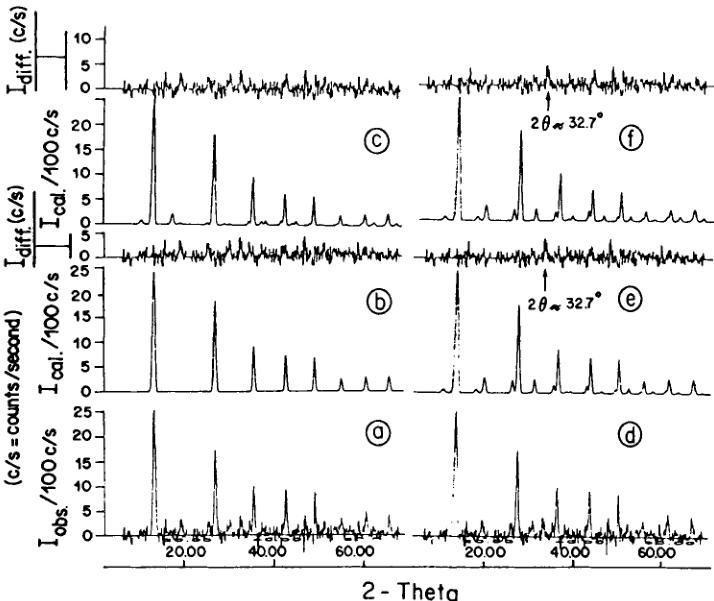

FIGURE 2 Observed, calculated and difference neutron powder diffraction intensities of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) boracite in the paramagnetic state at 36 K (only nuclear contribution).

3.2 Magnetic Phase Transitions

The integrated neutron intensity of the (pseudo)-orthorhombic magnetic peak (101/011) as a function of temperature (Figure 1) confirms the second order character of the magnetic phase transition at \( \sim30 \) K, corresponding to \( T_{c1}=29 \) K, already revealed by previous studies of magnetoelectric effect, Faraday rotation and magnetic birefringence. On the other hand, the magnetic phase transition at \( \sim21 \) K was not observed in the present neutron diffraction experiments. As will be shown in the next section, the neutron diffraction data do not provide conclusive information on the nature of this transition (Figure 3). This feature, together with the already mentioned results of magnetization measurements, \( ^{11} \) suggests that the magnetic moment arrangements are essentially antiferromagnetic both in the magnetic phase above and in the one below 21 K, both probably very similar to one another. In order to limit the number of parameters, it will not be an unreasonable approximation to refine the magnetic structure of Ni—Br at \( T<21 \) K in terms of the magnetic space group \( Pc^{\prime}a2_{1}^{\prime} \) rather than in the triclinic one P1. The magnetic symmetry constraint matrix of magnetic space group \( Pc^{\prime}a2_{1}^{\prime} \) is shown in Table IV.

3.3 Magnetic Structures at 8 K and at 24 K

The low temperature neutron diffraction pattern at 8 K of Ni—Br boracite indicates that all magnetic reflections occur at reciprocal lattice positions of the nuclear reflections and therefore k = 0. The main magnetic contributions with pseudo-

FIGURE 3 X-ray powder diffraction difference intensities (23–36) K and (8–23) K or \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) boracite. Differences are mostly due to temperature dependent peak shift.

TABLE II

Upper part: Bond distances around the three metal sites of the orthorhombic \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) boracite calculated from i) the 36 K neutron data, ii) the 36 K and 10 K X-ray powder data and iii) the 293 K X-ray single crystal data taken from Reference 7. Lower part: Bond angles around halogen site (Ni—Br—Ni) at 293 K using the parameters given in Reference 7. Standardized deviation crrors are indicated in parentheses.

| Sample | Powder | Powder | Powder | Single crystal |

| Temperature | 36K(N) | 36K(X) | 10K(X) | 293K(X) |

| d(Å) | d(Å) | d(Å) | d(Å)7 | |

| Ni(1)-Br | 2.64(3) | 2.638(6) | 2.658(8) | 2.663(2) |

| 3.39(3) | 3.409(6) | 3.383(9) | 3.373(2) | |

| Ni(1)-O | 2.01(6) | 1.79(3) | 1.90(4) | 2.00(1) |

| 2.03(6) | 1.93(4) | 2.04(4) | 2.03(1) | |

| 2.04(8) | 2.12(4) | 2.04(5) | 2.03(1) | |

| 2.04(7) | 2.18(3) | 2.27(3) | 2.06(2) | |

| Ni(2)-Br | 2.65(7) | 2.66(1) | 2.62(2) | 2.669(5) |

| 3.37(7) | 3.37(1) | 3.41(2) | 3.376(4) | |

| Ni(2)-O | 2.02(8) | 1.92(4) | 2.00(4) | 2.01(1) |

| 2.04(6) | 1.93(4) | 2.05(4) | 2.014(9) | |

| 2.10(10) | 2.08(5) | 2.07(4) | 2.021(8) | |

| 2.14(6) | 2.27(5) | 2.08(5) | 2.046(8) | |

| Ni(3)-Br | 2.64(7) | 2.65(1) | 2.63(2) | 2.647(5) |

| 3.38(7) | 3.37(1) | 3.39(2) | 3.361(4) | |

| Ni(3)-O | 2.00(8) | 1.87(5) | 1.97(4) | 2.013(8) |

| 2.01(7) | 1.95(5) | 2.00(5) | 2.013(8) | |

| 2.02(8) | 2.11(5) | 2.08(4) | 2.019(9) | |

| 2.07(7) | 2.18(4) | 2.17(4) | 2.040(9) | |

| 90° super-exchange | 180° super-exchange | |||

| Ni(1)-Br-Ni(3) | 86.2(2)* | Ni(2)-Br-Ni(3) | 174.9(1)* | |

| Ni(1)-Br-Ni(2) | 86.3(2)* | Ni(3)-Br-Ni(2) | 174.6(1)* | |

| Ni(1)-Br-Ni(2) | 89.3(2)* | Ni(1)-Br-Ni(1) | 171.98(6)* | |

| Ni(1)-Br-Ni(3) | 89.2(2)* | |||

| Ni(1)-Br-Ni(2) | 95.8(2)* | |||

| Ni(1)-Br-Nic(3) | 96.8(2)* | |||

| Ni(2)-Br-Ni(1) | 87.6(2)* | |||

| Ni(2)-Br-Nic(2) | 89.3(1)* | |||

| Ni(3)-Br-Nic(3) | 90.0(1)* | |||

| Ni(2)-Br-Nic(3) | 92.92(8)* | |||

| Ni(3)-Br-Nic(2) | 87.44(7)* | |||

| Ni(3)-Br-Nic(1) | 88.4(2)* |

TABLE III

The displacement parameters of orthorhombic boracite \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) at \( T = 293\ K^{7} \) ( \( \beta_{11} \) , \( \beta_{22} \) and \( \beta_{33} \) from single crystal X-ray diffraction) and 10 K ( \( B_{iso} \) from powder X-ray diffraction)

| Temperature | 293K | 10K | |

| Atom | \( \beta_{11} \) | \( \beta_{22} \) | \( \beta_{33} \) |

| Ni(1) | 40(11) | -11(15) | 234(10) |

| Ni(2) | 195(25) | 67(19) | 88(13) |

| Ni(3) | 108(24) | 104(19) | 102(13) |

| Br | 297(10) | 185(12) | 222(6) |

TABLE IV

The symmetry constraint matrix of the magnetic space group \( Pc'a2_{1}^{\prime} \) used in the magnetic structural refinement

\[ \begin{pmatrix}{{{1}}}&{{{1}}}&{{{1}}} \\{{{1}}}&{{{1}}}&{{{-1}}} \\{{{-1}}}&{{{1}}}&{{{-1}}} \\{{{-1}}}&{{{1}}}\end{pmatrix} \]

FIGURE 4 Difference neutron powder diffraction diagrams of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) between 8 K and 36 K and between 24 K and 36 K.

orthorhombic indices of \( (h0l) \) (h ≠ 2n) (0kl) (l ≠ 2n), n = integer, do not follow the limiting conditions for possible reflections of the space group \( Pca2_{1}1' \) and may be attributed to antiferromagnetic ordering. From the difference diagram between the ordered and the paramagnetic state (8–36) K one may state that there exists also a small number of weak contributions at allowed nuclear reflection positions: \( (002)_{0} \) , \( (102/012)_{0} \) , \( (120/210)_{0} \) which indicate the presence of either a magnetic contribution and (or) slight structural changes in the temperature range 8–36 K. Both the two difference diagrams of (8–36) K and (24–36) K showed the same characteristic (Figure 4). The magnetic structure model of Co—I boracite proposed on the basis of neutron powder diffraction refinement \( ^{30} \) seems to be insufficient to describe some weak neutron diffraction reflections of the Ni—Br boracite in the antiferromagnetic/weakly ferromagnetic phase. After testing several magnetic structure models with a variety of magnetic moment directions in magnetic space group \( Pc'a2_{1}' \) , two “basic” magnetic models, I and II (Table V) have been found, both of which simulate the main reflections of the difference diagram of (8–36) K.

The refinement on the difference diagram for the “basic” magnetic structure

TABLE V

The refinement parameters of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) for two magnetic structure models (I and II) obtained from i) the difference neutron pattern (8–36) K, first line: "basic" models explaining only the main magnetic reflections; second line: final models explaining strong and weak magnetic reflections. ii) the final models from the 8 K full neutron pattern, third line. The positions of the nickel ions were taken from the crystal structure refinement at 36 K (neutron)

| Model I | |||||

| Atom | MxμB | MyμB | MzμB | MμB | arsin[Mz/Mt] |

| Ni(1) | 3.58(4) | 0 | 0 | 3.58(4) | 0° |

| 3.51(5) | 0 | 0.6(2) | 3.56(5) | 10° | |

| 3.24(11) | 0 | 0.7(3) | 3.3(1) | 12° | |

| Ni(2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 1.31(7) | 0.2(1) | 1.33(7) | 9° | |

| 0 | 1.2(1) | -0.5(4) | 1.3(2) | -23° | |

| Ni(3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | -1.31(7) | -0.5(1) | 1.40(8) | -21° | |

| 0 | -1.2(1) | -0.1(4) | 1.2(1) | -5° | |

\[ R_{m}=8.7\% \]

Rm = 19.5%

\[ R_{m}=9.8\%, R_{n}=3.95\%, R_{p}=4.08\%, R_{wp}=7.72\%, R_{exp}=2.84\%, \chi^{2}=8.80 \]

| Model II | |||||

| Atom | MxμB | MyμB | MzB | MμB | artg[My/Mz] |

| Ni(1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ni(1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ni[2] | 0 | 0 | 2.23(8) | 2.23(8) | 0° |

| 0 | 1.33(6) | 2.2(1) | 2.54(9) | 31° | |

| 0 | 1.2(1) | 3.0(2) | 3.25(2) | 22° | |

| Ni[3] | 0 | 0 | 3.0(1) | 3.0(1) | 0° |

| 0 | -1.33(6) | 3.0(1) | 3.2(1) | -24° | |

| 0 | -1.2(1) | 1.9(2) | 2.3(2) | -32° | |

| Rm = 33.0% | |||||

| Rm = 19.0% | |||||

| Rm = 13.47%, Rn = 3.96%, Rp = 4.19%, Rwp = 7.72%, Rexp = 2.84%, χ² = 8.79 | |||||

model I with one parameter, \( K_{x} \) (1), converged to \( R_{m} = 8.75\% \) . The refinement for the basic model II with two parameters, \( K_{z} \) (2) and \( K_{z} \) (3), converged to \( R_{m} = 33.0\% \) . It should be noted that the residual factors ( \( R_{m} = 8.76\% \) and \( R_{m} = 33\% \) respectively) of the two “basic” magnetic structure models do not indicate a preferred refinement. Some weak magnetic reflections are considered in the “basic” magnetic structure model II, but not in the magnetic structure model I. The simultaneous refinement of these three parameters (i.e. two magnetic structure models) favours model II by converging to \( R_{m} = 32.2\% \) (Table V). In model II the magnetic moment directions of the \( Ni^{2+} \) ions are essentially located in the \( (100)_{0} \) -plane. This is in agreement with the observation that the magnetic susceptibility, \( \chi_{11} \) , i.e. perpendicular to that \( (100)_{0} \) plane is the largest component of the tensor \( (\chi_{11} > \chi_{22} > \chi_{33}) \) , \( ^{11} \) since the direction of the smallest susceptibility normally comes close to the direction of the magnetic moment.

The weak reflections at allowed nuclear reflection positions may be indexed by taking account of a small ferromagnetic contribution of the moments of \( \mathrm{Ni}(2)^{2+} \)

and \( \mathrm{Ni}(3)^{2+} \) along the pseudo-orthorhombic \( b_{0} \) -axis direction. The appearance of the weak ferromagnetic moment along the crystallographic pseudo-orthorhombic \( b_{0} \) -axis, \( \sim0.06\ \mu_{B}/atom \) , at 8 K, permits us to put a constraint for the antiferromagnetic coupling between \( \mathrm{Ni}(2) \) and \( \mathrm{Ni}(3) \) in the \( b_{0} \) -direction during the refinements of model I and of model II, both from the difference diagram (8–36) K and the full diagram at 8 K. The results of the refinements are listed in the Table IV. The (8–36) K difference diagram together with the two calculated basic magnetic reflections are shown in Figure 5. The calculated difference diagrams (Figure 5e) indicate that there is a weak contribution at \( 2\theta = 32.7^{\circ} \) , overlapping with the strong nuclear reflection \( (220/004)_{0} \) , which is not derived by the two models. This may be caused by slight nuclear structure changes or variation of the atomic displacement parameters.

Analogously to the crystal structures in the orthorhombic boracites (Fe—Cl, Fe—Br and Fe—I boracites: Reference 27, 28, 29; Ni—Br, Reference 7; Ni—Cl, Co—Br: Reference 26) the magnetic structure of Ni—Br also shows two different types of Ni ions. The \( Ni^{2+} \) ions of both the Ni(2) and Ni(3) sites, form mutually

FIGURE 5 a) and d): the difference neutron powder diffraction diagram of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) boracite between 8 and 36 K; b): the calculated neutron intensities of the "basic" magnetic structure model I; c): the calculated neutron intensities of the "basic" magnetic structure model II; e): refined neutron reflection intensities of the magnetic structure models I and the difference intensities of the observed and the calculated intensities; f): refined neutron reflection intensities of the magnetic structure model II and the difference intensities of the observed and the calculated intensities.

perpendicular Ni(2)—Br—Ni(3) chains in the \( (001) \) -orthorhombic planes and have similar magnetic moment. However, the moments of the ions of the Ni(1) site, forming the Ni(1)—Br—Ni(1) chains along the \( [001] \) -orthorhombic direction, differ notably from the moments of the Ni(2) and Ni(3) sites.

3.4 Magnetic Structure Models

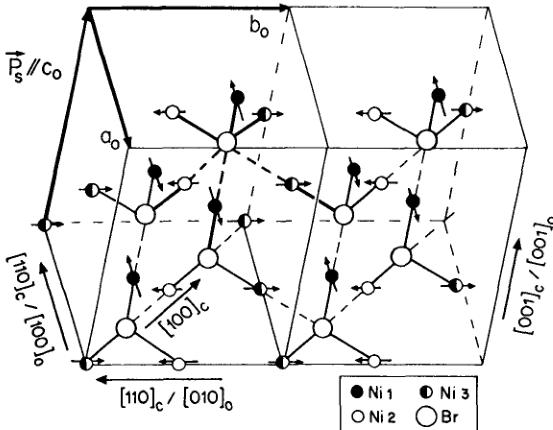

In model I (Figure 6), the magnetic structure of Ni—Br boracite at low temperature \( (T < 30\;\mathrm{K}) \) is mainly characterized by an antiferromagnetic magnetic moment arrangement on the Ni(1) site in the \( [100]_{0} \) -direction with a small tilting of about \( 10^{\circ} \) at 8 K towards the \( [001]_{0} \) -direction. The magnetic moments of the Ni(2) and Ni(3) sites are ferromagnetically ordered along the \( [010] \) -pseudo-orthorhombic direction with an antiferromagnetic coupling between them. Therefore the structure corresponds to a three dimensional canted moment arrangement with \( a_{0} \) as main axis of antiferromagnetism. The ordered magnetic moment values at the three \( Ni^{2+} \) sites are \( 3.56(5)\mu_{B} \) , \( 1.33(7)\mu_{B} \) , \( 1.40(8)\mu_{B} \) for Ni(1), Ni(2) and Ni(3), respectively. The magnetic moment components of Ni(2) and Ni(3) along the \( c_{0} \) -direction are in fact very small and may be neglected in the discussion.

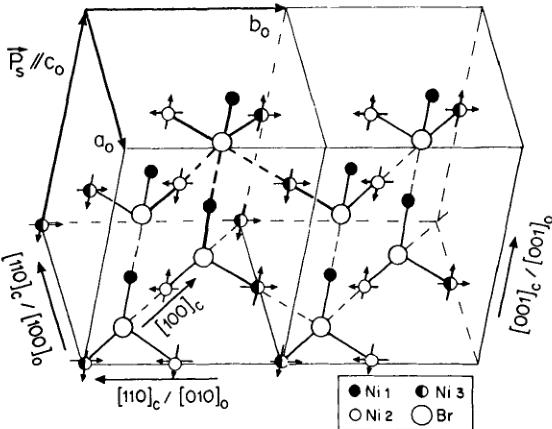

In model II (Figure 7), the moments of the Ni(2) and Ni(3) ion sites are mainly antiferromagnetically ordered in the \( (100)_{0} \) -planes. Magnetic moment vector tilting of about \( 31^{\circ} \) and \( -24^{\circ} \) from the \( c_{0} \) direction toward the \( b_{0} \) direction for Ni(2) and Ni(3), respectively, are calculated from the refinement results (Table V). In that model no magnetic ordering was found for the ions of the Ni(1) site. Figure 7

FIGURE 6 The magnetic structure model I of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) boracite at T = 8 K represented in the orthorhombic coordinate system. The small solid circles, open circles and half-solid circles denote \( \mathrm{Ni}(1) \) , \( \mathrm{Ni}(2) \) and \( \mathrm{Ni}(3) \) ions, respectively. The large open circles correspond to Br ions. The arrows indicate the magnetic moment components of nickel ions. The small ferromagnetic moment components along \( [001]_{0} \) pseudo-orthorhombic direction are omitted in the figure.

FIGURE 7 The magnetic structure model II of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) boracite at \( T = 8~K \) represented in the orthorhombic coordinate system. The small solid circles, open circles and half-solid circles denote \( \mathrm{Ni}(1) \) , \( \mathrm{Ni}(2) \) and \( \mathrm{Ni}(3) \) ions, respectively. The large open circles correspond to Br ions. The arrows indicate the magnetic moment components of nickel ions.

schematizes the magnetic structure of model II. An X-ray powder diffraction refinement of the nuclear structure of Ni—Br at 10 K shows a significant difference of atomic displacement parameters between the three nickel ion sites \( [B_{\mathrm{iso}}(\mathrm{Ni}1)=2.4(3), \mathrm{B}_{\mathrm{iso}}(\mathrm{Ni}2)=0.2(2), \mathrm{B}_{\mathrm{iso}}(\mathrm{Ni}3)=0.3(2)\mathring{\mathrm{A}}^{2}] \) . This may indicate that the thermal vibration energy of the Ni(1) site ions is still greater than the magnetic interaction energy at 10 K, so that the magnetic long range ordering of \( \mathrm{Ni}(1)^{2+} \) ions would occur at very low temperatures only.

Since the refined magnetic moment of the nickel ion has a value of \( 3.56(5)\mu_{B}/ \) atom for the Ni(1) site in model I, and \( 3.2(1)\mu_{B}/ \) atom for the Ni(3) site in model II (Table V), i.e., larger than the spin only value, \( M=2\sqrt{S(S+1)}\mu_{B}=2.83\mu_{B}/Ni^{2+} \) , one can conclude that the orbital contribution to the moment is by far not quenched. This is in agreement with a typical average moment value of \( 3.2\mu_{B} \) for \( Ni^{2+} \) ions showing clearly an orbital contribution as is the case for all 3d-transition metal ions with more than 5 electrons in the 3d orbitals. \( ^{31} \) The previous ESR studies of Cd—I and Cd—Cl boracites doped with nickel \( ^{32} \) and of Zn—Cl boracite doped with copper \( ^{33} \) showed an anisotropy of the g factor of about 20–25%. This anisotropy may also lead to a higher magnetic moment value in our refinement of model I.

The difference neutron diffraction diagram of Ni—Br boracite between 24 and 36 K shows the same characteristics as the one between 8 and 36 K (Figure 4). The two magnetic structure models refined for 8 K were used for magnetic structure refinement of the difference diagram (24–36) K. The tilting of the magnetic moment of Ni(1) ions towards the \( c_{0} \) -direction is smaller at 8 K than that at 24 K in model I. The magnetic moment magnitudes of the ions are smaller at 24 K than at 8 K.

which is easy to explain by the enhanced thermal vibration of the ions. The refined results are listed in Table VI.

3.5 Possible Magnetic Exchange Pathways in Ni—Br Boracite

i) Cation-Cation direct exchange interactions. According to Goodenough's prediction, \( ^{34,35} \) this type of exchange is possible and greatest when two neighboring octahedra share a common edge, the \( t_{2g} \) orbitals are half filled, \( e_{g} \) orbitals are empty and the distances between the cations are small. In our case, the distances between the nickel ions are large [3.85-3.91 (2) Å, see Table II], and the \( e_{g} \) orbitals are at least half filled, thus the interaction is presumably very weak and of antiferromagnetic nature. Due to the interruption of the Ni—Br—Ni chains in the orthorhombic phase, the pathway of Cation-Cation direct exchange from one tetrahedron (Ni1, Ni2, Ni3, Br) to a neighbouring one is expected to be very much weakened due to the strong deformation of the nickel octahedra around the Br atoms (Table II). The contribution of this type of interaction can therefore be considered as negligible.

ii) Cation-Cation superexchange interaction via an anion. The \( 90^{\circ} \) bond angle superexchange usually leads to a ferromagnetic ordering and \( 180^{\circ} \) bond angle superexchange usually gives rise to antiferromagnetic ordering. \( ^{[33,34]} \) In the case of Ni—Br both of these types of magnetic interaction would be expected to be strongly weakened because of the interruption of the metal-halogen chains below the cubic-to-orthorhombic phase transition (Table II) by the creation of long Ni—Br distances (between 3.37 Å and 3.39 Å!) for Ni(1), Ni(2) and Ni(3) along the three pseudocubic [100]-directions. However, because an important increase of the Néel-temperature and the Curie-Weiss temperature is observed in the sense Ni—Cl (9 K)→Ni—Br (30 K)→Ni—I (61.5 K) boracite, \( ^{[12,12a]} \) some —Ni—Br—Ni—superexchange seems to contribute non-negligibly to the spin ordering in spite of the long Ni—Br distances, in particular with increasing halogen atomic number. Whereas

TABLE VI

The refined parameters of \( Ni_{3}B_{7}O_{13}Br \) for two magnetic structure models (I and II) obtained from the difference neutron pattern (24–36) K. The positions of the nickel ions were taken from the crystal structure refinement at 36K

| Model I | |||||

| Atom | MxμB | MyμB | MzμB | MtμB | arsin[Mz/Mt] |

| Ni(1) | 2.4(1) | 0 | 0.9(1) | 2.58(7) | 20* |

| Ni(2) | 0 | 1.14(9) | 0 | 1.14(9) | 0* |

| Ni(3) | 0 | -1.14(9) | 0 | 1.14(9) | O* |

| Rm = 48.8% | |||||

| Model II | |||||

| Atom | MxμB | MyμB | Mz μB | MtμB | artg(My/Mz) |

| Ni(1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ni(2) | 0 | 1.20(8) | 2.1(1) | 2.4(1) | 30* |

| Ni(3) | 0 | -1.20(8) | 1.4(1) | 1.8(1) | -41* |

| Rm = 50.5% | |||||

the \( \sim180^{\circ} \) -superexchange could be expected to be strongly weakened owing to the interrupted \( -Ni-Br-Ni-Br- \) chains along the cubic (100) directions, the \( 90^{\circ} \) -superexchange, usually leading to ferromagnetic moment arrangement, and operating in the \( Ni_{3}-Br \) pyramids with short Ni—Br-distances ( \( 2.64\AA \) ) could be expected to be stronger. However, the triangular arrangement of \( Ni^{2+} \) ions in the base of these triangular pyramids represents a model configuration, with a strong tendency to provoke frustration of magnetic moment ordering. \( ^{36} \) Nonordering of the magnetic moment of one of the ions may then turn out to be the signature of frustration. In order to analyse the magnetic structure of such a potential frustration, more sophisticated programmes for structure refinements would have to be used.

iii) Cation'-Anion-Cation''-Anion-Cation' superexchange interaction. The \( 180^{\circ} \) Cation'-Anion-Cation''-Anion-Cation' superexchange interaction is similar to the \( 180^{\circ} \) Cation-Anion-Cation superexchange interaction, resulting usually in antiferromagnetic ordering. But the interaction magnitudes are much reduced and of the order of 8 K for the spin ordering temperature, as e.g. in the case of the \( -Co^{2+}-O^{2}-W^{6+}-O^{2}-Co^{2+} \) -interaction in \( Pb_{2}CoWO_{6} \) . \( ^{37} \) An average “through bond length” \( ^{38} \) of 7.00(2) Å is found on averaged \( -Ni-O-B-O-Ni- \) pathways for orthorhombic Ni—Br boracite. Every nickel atom has twenty \( -Ni-O-B-O-Ni- \) type pathways, four of which are nearly co-planar and co-linear. This may result in a quite large total magnetic interaction strength. Since the magnetic interaction via such pathways is weak, a slight intrinsic or extrinsic disturbance may break magnetic ordering. For example, an atomic thermal vibration (intrinsic), or a weak mechanical force (extrinsic) may change the magnetic states. One may argue that this type of pathway plays an important role in the antiferromagnetic behavior of the magnetic phases of Ni—Br and also in the other magnetic boracite compounds. This conjecture has to be compared with a similar type of pathway, \( -M-O-P-O-M- \) , which has been discussed for the compounds \( \mathrm{KBaFe_{2}(PO_{4})_{3}} \) , \( ^{39} \) \( \mathrm{NaFeP_{2}O_{7}} \) , \( ^{40,41} \) \( \mathrm{Na_{3}Fe_{2}(PO_{4})_{3}} \) \( ^{42} \) and \( \mathrm{Fe_{3}(PO_{4})_{2}} \) . \( ^{38} \)

CONCLUSIONS

The neutron powder diffraction spectra of the weakly ferromagnetic/ferroelastic orthorhombic (21 K–30 K) and triclinic \( (T < 21\;\mathrm{K}) \) phases clearly show antiferromagnetic spin ordering, but they are indistinguishable from one another. Moreover, they do not “see” the weakly ferromagnetic symmetry of both phases, which has fortunately been established previously with magnetic space groups \( Pc^{\prime}a2_{1}^{\prime} \) and P1, respectively, on the basis of optical domain studies, magnetic, dielectric and magnetoelectric measurements, nuclear structure studies and by using symmetry considerations.

The spectra at 8 K and at 24 K being practically identical, suggest only minor changes to spin directions to occur upon going from the orthorhombic to the triclinic phase. This fact, together with the higher magnetic intensities at 8 K pleaded for refinement in \( Pc^{\prime}a2_{1}^{\prime} \) at 8 K as a good approximation, rather than in P1 with 12 nickel sites, compared with 3 nickel sites only for space group \( Pc^{\prime}a2_{1}^{\prime} \) .

The magnetic structure refinement ended up with two models, “I” and “II”. In the first one (I) the nickel ions of all three structurally inequivalent sites participate

in the magnetic ordering, whereas model II requires the assumption of a paramagnetic state of those nickel ions located on the \( -Br-Ni-Br-Ni- \) chains along the \( 2' \) -axis and which show a higher atomic displacement factor than the two other ones. This model might e.g. be checked by probing locally the magnetic states of nickel by means of Mössbauer effect measurements using \( {}^{57} \) Fe as a detector.

For both models the understanding of the magnetic interaction pathways is not easy. The contribution of direct cation-cation exchange may be neglected because of the closest Ni—Ni distances (dNi—Ni > 3.8 Å) being too long. The expected \( 180^{\circ} \) superexchange interaction of antiferromagnetic nature along the \( -Ni-Br-Ni-Br- \) chains parallel \( [100]_{cub} \) as well as the ferromagnetic type \( 90^{\circ} \) -superexchange \( -Ni-Br-Ni-Br- \) is expected to be weak because these chains have long and short distances in the orthorhombic phase along all three \( [100]_{cub} \) -directions, leading to magnetically isolated tetrahedral \( Ni_{3}Br \) units. However, as stated above, there is experimental evidence that \( -Ni-Br-Ni- \) superexchange does contribute to the magnetic interaction. This fact would be consistent with model I.

A tempting, but may-be somewhat bold interpretation would be the assumption that the activity of \( -Ni^{2+}-O^{2-}-B^{3+}-O^{2-}-Ni^{2+}- \) pathways, having an average “through bond length” of 7.00 Å, are to a great extent responsible for the magnetic interaction and magnetic moment ordering. Such an interaction could be expected to be very weak, but owing to the fact that 20(!) such pathways are running through one \( Ni^{2+} \) site, the overall effect may not be negligible at all. If not negligible, this type of interaction would contribute to the spin ordering, independently of model I or II. A similar type of interaction pathway, \( -Fe^{3+}-O^{2-}-P^{5+}-O^{2-}-Fe^{3+}- \) , has been proposed to operate in certain iron phosphates. Further work is necessary to test these models. The development of a method for the direct growth of ferroelectric/ferroelastic single domains, large enough for neutron diffraction, would be highly rewarding.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. M. François for help in programming a plot program, to Mr. R. Cros for preparing figures and to the Swiss National Science Foundation for support.

REFERENCES

-

E. Ascher, H. Schmid and D. Tar, Solid State Commun., 2, 45 (1964).

-

A. Shaulov, W. A. Smith and H. Schmid, Ferroelectrics, 34, 219 (1981).

-

J.-P. Rivera and H. Schmid, Ferroelectrics, 55, 295 (1984).

-

H. Schmid, Rost Kristallov, 7, 32 (1967); [Growth of Crystals, 7, 25 (1969)].

-

H. Schmid and H. Tippmann, Ferroelectrics, 20, 21 (1978).

-

I. H. Brunskill and H. Schmid, Ferroelectrics, 36, 395 (1981).

-

S. C. Abrahams, J. L. Bernstein and C. Svensson, J. Chem. Phys., 75, 1912 (1981).

-

J.-P. Rivera, F.-J. Schaefer, W. Kleemann and H. Schmid, Jap. J. of Applied Physics, 24, Supplement 24-2, 1060 (1985).

-

J.-P. Rivera (1985), unpublished.

-

S. Y. Mao, J.-P. Rivera and H. Schmid, Ferroelectrics (1992), in press.

-

S. Y. Mao, H. Schmid, G. Triscone and J. Müller (1992), in preparation.

-

P. Tolédano, H. Schmid, M. Clin and J.-P. Rivera, Phys. Rev. B. (Cond. Matter), 32, 6006 (1985).

12a.G. Quézel and H. Schmid, Solid State Communications. 6, 447 (1968).

-

V. A. Koptsik, "Shubnikov Groups, Handbook on the Symmetry and Physical Properties of Crystal Structures," [in Russian], Izd. MGU, Moscow (1966).

-

K. Aizu, Phys. Rev., B7, 754 (1970).

-

W. von Wartburg, phys. stat. sol. (a), 21, 557 (1974).

-

H. Schmid, J. Physics Chem. Solids, 26, 973 (1965); see also H. Schmid and H. Tippmann, J. of Crystal Growth, 46, 723 (1979).

-

J. Schefer, P. Fischer, H. Heer, A. Isacson, M. Koch and R. Thut, Instr. Meth., A288, 477 (1990).

-

H. H. Paalman and C. G. Pings, J. Appl., Phys., 33, 2635 (1962).

-

H. M. Rietveld, J. Appl. Cryst., 2, 65 (1969).

-

A. W. Hewat, Harwell Report AERE-R7350 (1973).

-

R. A. Young, E. Prince and R. A. Sparks, J. Appl. Cryst., 15, 357 (1982).

-

V. Sears, Methods of Experimental Physics, 23A, p521.

-

R. E. Watson and A. J. Freeman, Acta Cryst., 14, 27 (1961).

-

D. B. Wiles and R. A. Young, J. Appl. Cryst., 14, 149 (1981).

-

W. Dreissig, R. Doherty and J. Stewart, Xtal 3.0 User's Guide (1989).

-

F. Kubel, S. Y. Mao and H. Schmid, Acta. Cryst., C48, 1167–1170 (1992).

-

F. Kubel and A.-M. Janner, Acta Cryst., C49, 657–659 (1993).

-

H. Schmid and J. M. Trooster, Solid State Comm., 5, 31 (1967).

-

J. M. Trooster, phys. stat. sol., 32, 179 (1969).

-

M. Clin, H. Schmid, P. Schobinger and P. Fischer, Phase Transitions, 33, 149 (1991).

-

C. Kittel, “Introduction to Solide State Physics,” Wiley & Sons, New York (1971).

-

K. Baberschke, S. Reich and E. Dormann, phys. stat. sol., 39, 139 (1970).

-

H. G. Hecht, J. Inorg. Nuclear Chem., 31, 2639 (1969).

-

J. B. Goodenough, J. Appl. Phys., 31S, 359 (1960).

-

J. B. Goodenough, “Magnetism and the Chemical Bond,” Wiley, New York 165 (1963).

-

P. Lacore, Thèse N° d'enregistrement: 88 LEMA 1010, Université de Maine, France (1988).

-

W. Brixel, J.-P. Rivera, A. Steiner and H. Schmid, Ferroelectrics. 79, 201 (1988).

-

J. K. Warner, A. K. Cheetham, A. G. Nord, R. B. Von Dreele and M. Yethiraj, J. Mater. Chem., 2(2), 191 (1992).

-

P. D. Battle, A. K. Cheetham, W. T. A. Harrison and G. L. Long, J. Solid State Chem., 62, 16 (1986).

-

T. Moya-Pizzaro, R. Salmon, L. Fournes, G. Le Flem, B. Wanklyn and P. Hagenmuller, J. Solid State Chem., 53, 387 (1984).

-

R. C. Mercader, L. Terminiello, G. J. Long, D. G. Reichel, K. Dickhaus, R. Zysler, R. Sanchez and M. Tovar, Phys. Rev., B42, 25 (1992).

-

D. Beltran-Porter, R. Olazcuaga, L. Fournes, F. Menil and G. Le Flem, Rev. Phys. Appl., 15, 1155 (1980)