| Transition Temperature | 25 K |

|---|---|

| Experiment Temperature | 5 K |

| Propagation Vector | k1 (0, 0, 0) |

| Parent Space Group | Fd-3m (#227) |

| Magnetic Space Group | I41/am'd' (#141.557) |

| Magnetic Point Group | 4/mm'm' (15.6.58) |

| Lattice Parameters | 6.96471 6.96471 9.84959 90.00 90.00 90.00 |

|---|---|

| DOI | 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b01498 |

| Reference | E. Pomjakushina, V. Pomjakushin, K. Rolfs, J. Karpinski and K. Conder, Inorganic Chemistry (2015) 54 9092-9097. |

| Label | Element | Mx | My | Mz | |M| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn_1 | Mn | 0.0 | 0.81 | 1.66 | 1.85 |

| Tm_1 | Tm | 0.0 | -0.05 | 2.31 | 2.31 |

New Synthesis Route and Magnetic Structure of \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) Pyrochlore

Ekaterina Pomjakushina, \( ^{*} \) \( ^{\dagger} \) Vladimir Pomjakushin, \( ^{\ddagger} \) Katharina Rolfs, \( ^{\dagger} \) Janusz Karpinski, \( ^{\dagger} \) and Kazimierz Conder \( ^{\dagger} \)

\( ^{\dagger} \) Laboratory for Developments and Methods, Paul Scherrer Institut (PSI), 5232 Villigen, Switzerland

\( ^{\ddagger} \) Laboratory for Neutron Scattering and Imaging, Paul Scherrer Institut (PSI), 5232 Villigen, Switzerland

magnetic (AFM) canting, suggesting a lowering of the initial cubic crystal symmetry. The magnetic transition is accompanied by a small but very visible magnetostriction effect. Using symmetry analysis, we have found a solution for the AFM structure in the maximal Shubnikov subgroup \( Id_{1}/am'd' \) .

INTRODUCTION

A few important factors influence any successful synthesis of novel electronic materials: a reactivity of the used precursors, an applied type of the synthesis process (solid state reaction, reactions in a liquid phase, reaction in a gas phase), and the thermodynamic parameters. Besides temperature, pressure also is a fundamental thermodynamic variable of every chemical reaction. An influence of the pressure on a solid-state reaction is dependent on the type of the applied pressure medium. By applying just a hydrostatic pressure, a reduced evaporation of the volatile components during synthesis, a structural rebuilding of the resulting solid (bond lengths and coordination number change) and higher reactivity (reacting powder grains are brought closer together) can be expected. If the applied gas medium is an active component of the system (such as oxygen in the case of oxides), the thermodynamic equilibrium will be changed. This causes modification of the phase diagrams and changes in the defect equilibria of a solid. In the case of oxidizing gases, especially oxygen, this can result in a stabilization of the unusually high oxidation states of cations and allow the synthesis of compounds that are thermodynamically unstable in air (that is, at low oxygen partial pressure).

Pyrochlore oxides containing transition metals show geometrical magnetic frustration, which is interesting because of the possible realization of novel, exotic, magnetic ground states. The cubic pyrochlore oxides \( (Fd3^{m}) \) have a general formula of \( A_{2}B_{2}O_{7} \) , where A is usually a trivalent rare-earth metal and B is a tetravalent transition metal. Pyrochlore structure is based on a network of corner-sharing \( BO_{6} \) octahedra similar to that observed in perovskites \( ABO_{3} \) . The A atoms are in the center of the hexagonal rings formed by oxygens (O1, located at the 48f positions) with two more oxygens (O2, at the 8b positions) located above and below the rings. Both A and B cations in this structure are located in the corners of tetrahedra. Such a configuration can lead to a geometrical magnetic frustration.

There are almost 20 tetravalent ions (B-site) that can form pyrochlore compounds with rare-earth ions (A-site). Sub-ramanian and Sleight \( ^{1} \) have built a stability-field map for these materials, which displays the stability limits for the pyrochlore structure at ambient pressure, depending on a so-called stability range factor, which is defined as the ionic radius ratio \( (r_{\mathrm{A}}^{+}/r_{\mathrm{B}}^{+}) \) . For stability at ambient pressure, this ratio resides in the range between 1.36 and 1.71. Based on this map, it looks that the rare-earth \( Mn^{4+} \) pyrochlores cannot be synthesized at ambient pressure and require high pressures for the stabilization. This is mainly due to the small size of the \( Mn^{4+} \) ion, compared to the trivalent rare-earth cations giving a stability range factor of >1.84.

The first report about the successful synthesis of \( A_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) (A = Y, Tl) appeared in 1979 by Fujinaka et al. \( ^{2} \) Both compounds were synthesized at 1000–1100 °C and pressures of 3–6 GPa. About 10 years later, a hydrothermal method of synthesis of \( A_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) ( \( A = Y, Dy–Lu \) ) in sealed gold ampules at 0.3 GPa and 500 °C \( ^{3} \) and high-pressure synthesis of \( A_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) (a = Sc, Y, In, Tl, Tb–Lu) at pressures of 5–8 GPa.

and temperatures of 1000–1500 °C \( ^{4} \) was reported. Later, Shimakawa et al. \( ^{5} \) used a hot isostatic press method at 1000–1300 °C and only 0.4 kbar for the series with A = In, Y, and Lu, while, for A = Tl material, a pressure of 2.5 GPa and temperature of 1000 °C in a piston–cylinder apparatus were still required. All the above synthesizes were done in anvils with solid-state pressure medium without a controlled oxygen pressure atmosphere. According to the recent review by Gardner et al., \( ^{6} \) all these materials appear to be ferromagnetic (FM). An excellent agreement of the structural parameters was achieved by different groups, although a variety of the preparative conditions were applied.

In comparison to other pyrochlore families such as \( A_{2}Mo_{2}O_{7} \) , \( A_{2}Ti_{2}O_{7} \) , \( A_{2}Sn_{2}O_{7} \) , \( A_{2}Ru_{2}O_{7} \) , \( A_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) system was not explored much (especially some compositions, such as \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) ), perhaps due to ambient pressure instability and, consequently, a nontrivial synthesis. To the best of our knowledge, only two groups at the end of the 1980s were reporting on the synthesis of \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) . \( ^{3,4} \) Magnetization studies were done for \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) . Discrepant values for the Curie temperature \( T_{C} \) (14 K \( ^{4} \) and 30(5) K \( ^{3} \) ) and the Curie–Weiss constant \( \Theta \) (+56(8) \( ^{3} \) ) were reported. The observed large and positive \( \Theta \) value indicates strong ferromagnetic exchange interactions between the Mn moments. At low temperatures, a sharp increase in the susceptibility was observed, again indicating a possibility for long-range FM order.

In this work, we report new studies of the magnetic properties of \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) obtained by an oxidation of \( TmMnO_{3} \) at \( 1100\ ^{\circ}C \) and an oxygen pressure of 1300 bar.

Since the \( Tm^{3+} \) cation has one of the smallest radius among the rare-earth elements and, consequently, the tolerance factor is also the smallest, it has a big magnetic moment and a low neutron absorption, and no neutron diffraction studies were performed for \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) until now: we have decided to undertake investigation of this compound, synthesized by a novel high-pressure oxygen method.

■ EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Synthesis. The following reagents were used: \( Tm_{2}O_{3} \) (99.99% Aldrich) and \( MnO_{2} \) (99.997% Alfa Aestar). Initially, \( TmMnO_{3} \) was synthesized via a standard solid-state reaction. The respective amounts of the starting reagents were mixed, milled, and calcined at 1000–1200 °C during 100 h in air with intermediate grindings. The synthesized material was found to be phase pure (hexagonal phase), as proved by laboratory powder X-ray diffraction (XRD). \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) was obtained via the oxidation of 3 g of the starting material at 1100 °C and an oxygen pressure of 1300 bar for 20 h in the high-pressure setup. \( ^{7} \) The volume of oxygen used during the synthesis in this setup is reduced to 20 cm \( ^{3} \) by using double-chamber construction. The sample was placed in an alumina crucible connected tightly to an oxygen supply system of the autoclave. The crucible was placed in the furnace in the high-pressure chamber. In this chamber, the oxygen pressure in the crucible is balanced by the equal argon pressure outside the crucible. In this way, the volume of the oxygen under high pressure is only up to 20 cm \( ^{3} \) , while the volume of the entire chamber is \( \sim \) 4000 cm \( ^{3} \) . Both pressures were balanced by an electronic pressure control unit with remote control valves.

Measurements and Characterization. Oxygen content in the sample was determined by a thermogravimetric (TG) hydrogen reduction performed on Netzsch Model STA 449C analyzer equipped with a Pfeiffer Vacuum ThermoStar mass spectrometer. The same TG analyzer was used for the determination of the temperature stability range of the sample in pure helium and artificial air (21 vol % oxygen in helium). AC and DC magnetization \( (M_{\mathrm{AC}}/M_{\mathrm{DC}}) \) measurements were performed using Quantum Design PPMS at temperatures in the range of 2–300 K. The AC field amplitude and the frequency were 0.1 mT and 0.05 mT and 1000 Hz, respectively. Neutron powder diffraction measurements were carried out at High-Resolution Powder Diffractometer for Thermal Neutrons HRPT \( ^{8} \) at SINQ neutron spallation source (Paul Scherrer Institut (PSI), Switzerland). The refinements of the crystal structure parameters were done using FULLPROF \( ^{9} \) program, with the use of its internal tables for neutron scattering lengths. The symmetry analysis was performed using ISODISTORT tool based on ISOTROPY software, \( ^{10,11} \) BasiRep program \( ^{9} \) and software tools of the Bilbao crystallographic server. \( ^{12} \)

■ RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

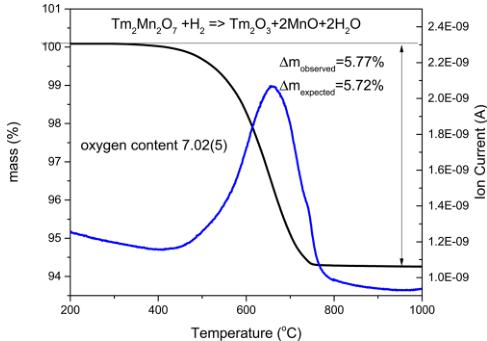

Phase Purity, Oxygen Stoichiometry, Thermal Stability. The laboratory XRD measurements, which were done at room temperature using Cu Kα radiation on a Bruker D8 diffractometer, have proven that the product of the oxidation reaction is a phase-pure compound with the cubic pyrochlore structure. Oxygen content determined by the thermogravimetric hydrogen reduction \( ^{13} \) was found to be 7.02(S). Figure 1

Figure 1. Thermogravimetric curve of the hydrogen reduction of \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) sample. The blue line shows a mass spectrometric signal for water \( (m/e = 18) \) .

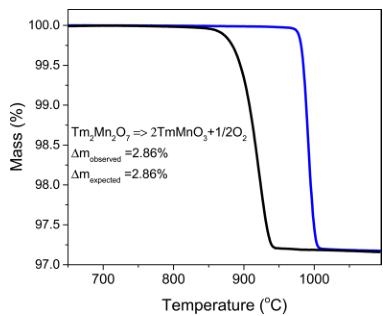

shows a thermogravimetric curve of the hydrogen reduction of \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}Oy \) sample together with a mass spectrometric signal for the water created during reduction \( (m/e = 18) \) . The thermal stability range of the synthesized compound was also checked by thermogravimetry. Figure 2 shows thermogravimetric curves

Figure 2. Thermogravimetric curves of \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) sample heated in helium (black line) and artificial air (blue line).

of the \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) sample heated in helium and artificial air. The thermal stability of the compound increases as the oxygen partial pressure increases. In helium, \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) starts to decompose at \( 850\;^{\circ}C \) , whereas in air, it is stable up to \( 950\;^{\circ}C \) . Using laboratory XRD analysis, we have identified the product of the thermal decomposition, which is hexagonal \( TmMnO_{3} \) . Opposite to the previous reports, where the synthesis was done starting from oxides, \( ^{3,4} \) here we have obtained a pure-phase compound by converting \( TmMnO_{3} \) at \( 1100\;^{\circ}C \) and an oxygen pressure of 1300 bar into \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) . This is a new promising route to stabilize \( Mn^{4+} \) pyrochlores that are thermodynamically unstable at ambient pressure. The chemical reaction is reversible, and upon heating, starting from \( 850\;^{\circ}C \) (at low oxygen partial pressures), \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) transforms back to \( TmMnO_{3} \) .

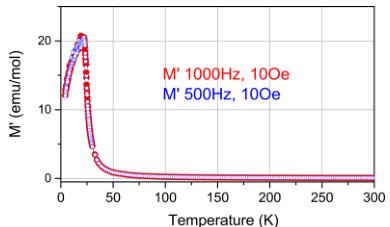

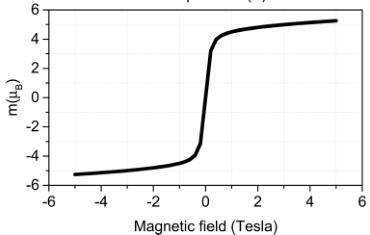

Magnetic Properties. Figure 3(top) shows the real part of the AC susceptibility measured at 0.1 mT and 0.05 mT and

Figure 3. (top) Temperature dependence of the real part of the AC susceptibility measured at 0.1 mT (blue) and 0.05 mT (red) and 1000 Hz. Fit of the high-temperature region (150–300 K) of magnetic susceptibility to Curie–Weiss law gives a value of \( T_{C} = 23.5 \) K. (Bottom) Plot of the magnetic moment in Bohr magneton per formula unit \( TmMnO_{3,5} \) as a function of applied field measured at 5 K.

1000 Hz, indicating a very sharp maximum at a temperature of \( \sim25 \) K, similar to that observed in \( Y_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) \( ^{14} \) \( Ho_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) , and \( Yb_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) \( ^{15} \) The fit of the high-temperature region (150–300 K) of magnetic susceptibility to Curie–Weis law gives a value of \( T_{C}=23.5 \) K. At the bottom of Figure 3, the magnetic moment, as a function of the applied field, is plotted for \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) at 5 K that is below the magnetic transition. No full saturation of magnetization was observed up to 5 T. This was already previously noticed for \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) by Troyanchuk at \( ^{4} \) . Those authors \( ^{4} \) proposed that the value of the f-d exchange in this compound is smaller than that in other rare-earth-manganese pyrochlores and the magnetic moment of the \( Tm^{3+} \) ion is in a paramagnetic state.

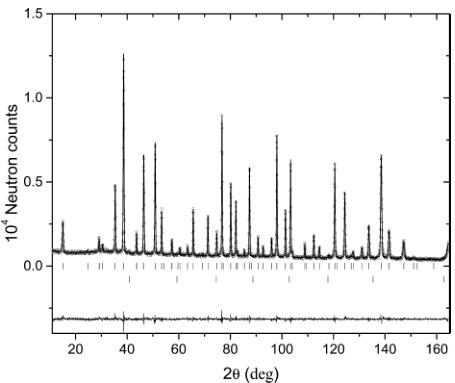

Magnetic Structure and Symmetry Analysis. The neutron diffraction studies have shown that the synthesized material contains a pure phase of a well-known \( ^{6,16} \) pyrochlore cubic structure with the space group \( Fd\bar{3}m \) (No. 227). Figure 4

Figure 4. Rietveld refinement pattern and the difference plot of the neutron diffraction data for the sample \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) at T = 30 K, measured at HRPT diffractometer with a wavelength of \( \lambda = 1.494 \) Å. The rows of tic marks show the Bragg peak positions for the main phase and for the V container.

shows the powder neutron diffraction pattern and the Rietveld refinement curve for \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) at T =30 K, above the Curie temperature \( T_{C} = 25 \) K. Structural parameters are listed in Table 1 (presented later in this work). Note that, in the pyrochlore structure, Tm and Mn occupy the positions in the inversion centers and their positions can be swapped, provided that the oxygen positions are also accordingly modified. So, in this second equivalent description of the structure, oxygen O1 occupies the 8b position \( \left(^{3}/_{8^{3}}/_{8^{3}}/_{8^{3}}\right) \) ; O2 remains at the same (48f) position, but x should be changed to \( -x + ^{3}/_{4} \) .

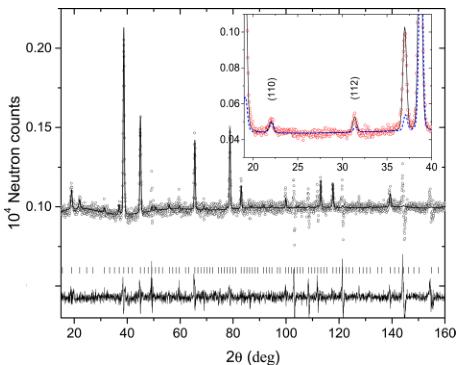

Figure 5 shows the Rietveld refinement pattern and the difference plot of the difference magnetic neutron diffraction pattern between 5 K and 30 K. All magnetic peaks are indexed with propagation vector k = 0. The main contribution to the magnetic intensity originates from the FM ordering of both types of magnetic atoms Mn and Tm. However, there is a small but very visible AFM contribution. For example, the magnetic Bragg peaks (200) and (220) shown in the inset of Figure 5 have no FM contribution. The experimental intensity of the very first magnetic peak (111) is also underestimated without AFM contribution. The magnetic atoms Mn and Tm occupy the positions 16d and 16c, which have the same symmetry (3m). The decomposition of the magnetic representation for them into irreducible representations (irreps) of \( \Gamma \) -point reads \( \Gamma_{2}^{+}(\tau_{3}) \oplus \Gamma_{3}^{+}(\tau_{5}) \oplus \Gamma_{5}^{+}(\tau_{7}) \oplus 2\Gamma_{4}^{+}(\tau_{9}) \) with the dimensions of irreps 1D, 2D, 3D, and 3D, respectively. The nomenclature for the irreps is given according to Campbell et al. \( ^{[11]} \) with Kovalev's notation in the parentheses. It is known from the magnetic susceptibility data and also from the previous neutron diffraction works \( ^{[6]} \) on similar pyrochlores that the magnetic structure is ferromagnetic (FM). This fact imposes restrictions on the possible irrep involved in the magnetic transition. One-dimensional real irrep \( \Gamma_{2}^{+} \) resulting in \( Fd3^{-}m' \) Shubnikov magnetic space group (MSG) does not allow FM configuration. Two-dimensional real irrep \( \Gamma_{3}^{+} \) does not allow FM, as well for any direction of the order parameter (OP) in the configuration space, resulting in magnetic group Fddd for the general OP direction (ab). The magnetic modes generated by three-dimensional real irrep \( \Gamma_{5}^{+} \) are also non-FM. The only irrep that

Figure 5. Rietveld refinement pattern and the difference plot of the difference magnetic neutron diffraction pattern between 5 K and 30 K (with an added artificial constant of \( 10^{3} \) ) for \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) measured at HRPT with a wavelength of \( \lambda = 1.886 \) Å. The line is the refinement pattern based on the magnetic model \( I4_{1}/am'd' \) shown in Table 1. The rows of tic marks show the magnetic Bragg peak positions. The inset shows fragment of diffraction pattern at T = 5 K with the dashed line showing the magnetic contribution. The indexing is given in the Shubnikov group (in the parent paramagnetic group, the indexes are (200) and (220)). The indicated Bragg peaks have magnetic contribution solely from the AFM components of the spins.

allows ferromagnetism is \( \Gamma_{4}^{+} \) . However, the representational approach alone is not very helpful here, because this 3D irrep enters two times in the magnetic decomposition resulting in at least six independent normal modes for each sort of the atoms, i.e., 12 parameters to be refined. This general case of irrep \( \Gamma_{4}^{+} \) corresponds to OP direction (abc) and reduces the symmetry down to the triclinic Shubnikov group \( P1^{-} \) . A more restrictive (by symmetry) approach is to use Shubnikov magnetic group symmetry. There are three special directions of the order parameter (a00), (aa0), and (aaa) that generate \( I4_{1}/am'd' \) , \( Imm'a' \) , and \( R3^{-}m' \) isotropy subgroups, respectively. Each of the above OP directions result in only one magnetic mode for \( \Gamma_{4}^{+} \) (magnetic mode defines specific magnetic configuration on all atoms of the same type and has only one parameter to be determined experimentally: its amplitude). The first two subgroups are the maximal subgroups of the gray paramagnetic group \( Fd3^{-}m1' \) . The group \( R3^{-}m' \) is not the maximal subgroup of the paramagnetic group, but is a subgroup of non-FM maximal subgroup \( Fd3^{-}m' \) , which is generated by \( \Gamma_{2}^{+} \) . For this reason, there is an additional independent antiferromagnetic mode in \( R3^{-}m' \) that makes magnetic atoms of the same type nonequivalent. The magnetic group \( Imm'a' \) is a maximal subgroup and generated by a single irrep, but accidentally it can be also generated by \( \Gamma_{5}^{+} \) with OP direction (0a -a). This is a rare exceptional case when two different irreps have the same MSG as the isotropy subgroup. Therefore, for the magnetic

Table 1. Crystal and Magnetic Structure Parameters in \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) in (a) Parent Paramagnetic Space Group \( Fd3^{-}m \) (No. 227, Origin Choice 2) at T = 30 K (b) in Magnetically Ordered State at T = 2 K in Shubnikov Magnetic Space Group \( I4_{1}/am'd' \) (No. 141,557, Origin Choice 2), Which is a Maximal Subgroup of the Gray Parent Group for 3D irrep \( \Gamma_{4}^{+} \) and Special Direction of Order Parameter \( (a00)^{a} \)

| (a) Fd3−m, T = 30 K | (b) I4/am′d′, T = 5 K | ||

| a, Å | 9.84959(9) | 6.96471 | |

| c, Å | 9.84959 | ||

| Tm | |||

| atom position | 16c | 8d | |

| x, y, z | 0, 0, 0 | 0, 0, 0 | |

| B, A2/m, μB | 0.094(9) | 0, m, mz | 0, −0.05(5), 2.31(5) |

| Mn | |||

| atom position | 16d | 8c | |

| x, y, z | 1/2, 1/2, 1/2 | 0, 0, 1/2 | |

| B, A2/m, μB | 0.033(23) | 0, m, mz | 0, 0.81(5), 1.66(4) |

| O1 | |||

| atom position | 8a | 4b | |

| x, y, z | 1/8, 1/8, 1/8 | 0, 1/4, 3/8 | |

| B, A2/m, μB | 0.159(24) | 0, 0, mz | 0, 0, 0 |

| O2 | |||

| atom position | 48f | 8e | |

| x, y, z | 0.4206(6), 1/8, 1/8 | 0, 1/4, 0.079 | |

| B, A2/m, μB | 0.212(10) | 0, 0, mz | 0, 0, 0, 0 |

| O2 | 16g | ||

| atom position | 0.2044, x + 1/4, 3/8 | ||

| x, y, z | m, x, −m, mz | ||

| B, A2/m, μB | |||

\( ^{a} \) Atomic displacement parameters B in \( \mathring{A}^{2} \) are given for the parent cubic group, magnetic moments m in Bohr magnetons are given for \( I4_{1}/am'd' \) group. Basis transformation from cubic to tetragonal cell reads: \( (0, 1/2, -1/2) \) , \( (0, 1/2, 1/2) \) , \( (1,0,0) \) with origin shift \( (-1, 1/4, -1/4) \) . Magnetic structure is FM along z-axis with AFM canting along the x- and y-axes as shown in Figure 6. Note that we cannot experimentally distinguish between the Tm and Mn magnetic moments, because they occupy identical symmetry positions. Crystal structure parameters in the Shubnikov group are derived from the parent group, according to the above transformation. See the text on the tetragonal distortions.

group \( Imm'a' \) one has an additional AFM mode as well, similar to the case of \( R3'm' \) .

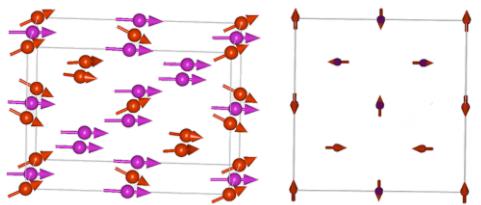

The most symmetric solution is given by the maximal tetragonal subgroup \( I4_{1}/am'd' \) that forces all spins of the same type of atom (Mn or Tm) to be the same by symmetry, being the highest allowable by the symmetry solution. Since \( \Gamma_{4}^{+} \) enters the magnetic decomposition twice, there are two parameters to be refined: the FM component along the z-axis and AFM component in the perpendicular plane for each type of magnetic atom Tm and Mn. The magnetic structure details and the refined magnetic moments are shown in Table 1. As mentioned above, we cannot distinguish between Tm and Mn positions in the magnetic structure, because they are the only atoms with a magnetic contribution. Therefore, the assignment of the moments per atom type is conditional. Interestingly, the AFM component of moment is converged to the nonzero value for only one type of atom, which has smaller value of FM component and smaller overall spin (it is labeled as Mn in Table 1). The only way to distinguish Tm from Mn would be by using the small differences in Q dependence of the magnetic form factors \( f(Q) \) of \( Mn^{4+} \) and \( Tm^{3+} \) ions, but our experimental accuracy does not allow this. Figure 6 shows the best-fit magnetic configuration with the parameters from Table 1.

Figure 6. (Left) Unit cell of \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) showing the magnetic structure in Shubnikov group \( I4_{1}/am'd' \) (No. 141.557). Tm and Mn atoms are represented by violet and red circles. The structure corresponds to the structure listed in Table 1. (Right) Projection of the structure on ab-plane. Only one type of atom (labeled as Mn) shows AFM canting.

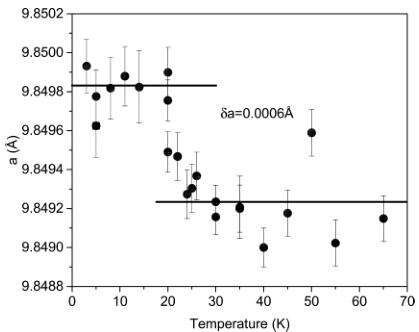

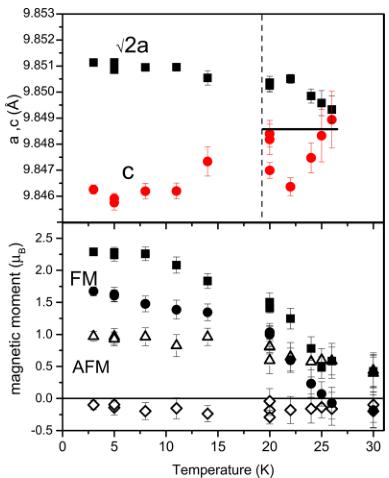

Figure 7 shows the temperature dependence of the lattice constant refined in the cubic metric of \( Fd3^{\prime}m \) space group. One

Figure 7. Temperature dependence of the lattice constant refined in the cubic metric.

can see an abrupt increase in the lattice constant below \( T_{C} \) implying a presence of a spin–lattice interaction. Ferromagnetic ordering is not possible in the cubic symmetry and the best magnetic structure solution that we have found is in the tetragonal symmetry. To further check possible tetragonal distortions, we performed the following analysis. We have made the fit of the crystal metric as a function of temperature in the \( I4_{1}/am'd' \) magnetic group, keeping all structure parameters fixed by the cubic structure and with the peak shape parameters fixed by their values above \( T_{C} \) . Figure 8 shows lattice constants

Figure 8. (Top) Temperature dependence of the lattice constants refined in the tetragonal metric. There is no difference in the fit quality \( \chi^{2} \) with cubic metric for T > 19 K and no convergence above the magnetic transition \( (T > 25\ \text{K}) \) . The horizontal line shows the value of the lattice constant above \( T_{C} \) refined in the cubic metric. (Bottom) Magnetic moment components as a function of temperature. Closed symbols show FM moments for Tm (squares, ■) and Mn (circles, ●) along the c-direction; open symbols are AFM moments for Mn (triangles, △) and Tm (rhombus, ◇) in the ab plane. The assignment of the moments per atom type is conditional. We cannot experimentally distinguish Tm and Mn magnetic moments, because they occupy identical symmetry positions.

a and c (top) and the magnetic moment components (bottom), each as a function of temperature. One can see that, at temperatures below \( T_{C} \) there is a pronounced split of the lattice constants. The distortions are significantly bigger than the change in a cubic constant a, because the tetragonal lattice constants a and c increase and decrease respectively below \( T_{C} \) which is accompanied by the increase in the magnetic moments.

According to the inelastic neutron scattering (INS) experiment with isostructural \( Tm_{2}Ti_{2}O_{7} \) \( ^{17} \) , the \( Tm^{3+} \) ion is in a singlet ground state. We have tried to fit the experimental data using only one type of atom, applying the assumption that \( Tm^{3+} \) has no magnetic moment. However, even without any symmetry constraints for Mn-spins, it is not possible to obtain any reasonable description of the experimental magnetic Bragg peak intensities. Apparently, one needs the second spin on Tm to get correct interference terms in the magnetic structure factor. An additional argument in favor of our magnetic model

with both Mn and Tm spins comes from the fact that the total FM moment of Mn and Tm from neutron diffraction is \( 4.2 \mu_{B} \) being in good correspondence with the saturation values of DC magnetization of Figure 3 (bottom). There might be several reasons accounting for the contradiction with the previous INS data on \( Tm_{2}Ti_{2}O_{7} \) . The \( Tm^{3+} \) ion is known to be a van Vleck ion, like other rare-earth ions with an even number of electrons such as \( Eu^{3+} \) , \( Ho^{3+} \) , \( Pr^{3+} \) , and \( Tb^{3+} \) , so the energy distance between the singlet and next doublet state is not large. In this case, the magnetic moment on Tm can be induced by the molecular field from ordered Mn spins, similar to those observed in \( Eu_{1-x}Y_{x}MnO_{3} \) . \( ^{18} \) Another possible reason could be cubic symmetry being reduced to tetragonal symmetry, because of FM ordering.

■ CONCLUSIONS

In this work, we show a novel way of converting a thermodynamically stable hexagonal \( TmMnO_{3} \) (space group \( P6_{3}cm \) ) compound to the metastable \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) with the cubic pyrochlore-type structure at \( 1100\;^{\circ}C \) and an oxygen pressure of 1300 bar. The unique high-temperature high-pressure apparatus used in this work allows one to synthesize materials in cubic centimeter ( \( cm^{3} \) ) amounts, which are sufficient to collect good quality neutron scattering data. New studies of magnetic properties of \( Tm_{2}Mn_{2}O_{7} \) by means of a high-resolution neutron powder diffraction have shown that, below 25 K, there is a transition to a ferromagnetically ordered phase with additional antiferromagnetic canting, which suggests that the crystal symmetry is lower than cubic one. Using symmetry analysis, which has been presented here in detail, we have found the most symmetry restrictive maximal Shubnikov subgroup \( I4_{1}/am^{\prime}d^{\prime} \) that fits the experimental data very well. The magnetic transition is accompanied by a very visible magnetostriction effect.

AUTHOR INFORMATION

Corresponding Author \( ^{*} \) E-mail: ekaterina.pomjakushina@psi.ch.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

■ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the allocation of the beam time at the HRPT diffractometer of the Laboratory for Neutron Scattering and Imaging (Paul Scherrer Institut (PSI), Switzerland). The authors thank SNF Sinergia project “Mott Physics beyond Heisenberg Model” for the support of this study. The work was partially performed at the neutron spallation source SINQ.

■ REFERENCES

(1) Subramanian, M.; Sleight, A. Rare earth pyrochlores. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths, Vol. 16; Gschneidner, K. A., Jr., Eyring, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1993; Chapter 107, pp 225–248.

(2) Fujinaka, H.; Kinomura, N.; Koizumi, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Kume, S. Mater. Res. Bull. 1979, 14, 1133–1137.

(3) Subramanian, M.; Torardi, C.; Johnson, D.; Pannetier, J.; Sleight, A. J. Solid State Chem. 1988, 72, 24–30.

(4) Troyanchuk, I.; Derkachenko, V.; Shapovalova, E. Phys. Stat. Solidi A 1989, 113, K249–K251.

(5) Shimakawa, Y.; Kubo, Y.; Hamada, N.; Jorgensen, J.; Hu, Z.; Short, S.; Nohara, M.; Takagi, H. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1999, 59, 1249–1254.

(6) Gardner, J. S.; Gingras, M. J. P.; Greedan, J. E. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 53–107.

(7) Karpinski, J. Philos. Mag. 2012, 92, 2662–2685.

(8) Fischer, P.; Frey, G.; Koch, M.; Könnecke, M.; Pomjakushin, V.; Schefer, J.; Thut, R.; Schlumpf, N.; Bürge, R.; Greuter, U.; Bondt, S.; Berruyer, E. Phys. B 2000, 276–278, 146–147.

(9) Rodriguez-Carvajal, J. Phys. B 1993, 192, 55–69. (Also available via the Internet at: www.ill.eu/sites/fullprof/.)

(10) Stokes, H. T.; Hatch, D. M. Isotropy Subgroups of the 230 Crystallographic Space Groups; World Scientific: Singapore, 1988.

(11) Campbell, B. J.; Stokes, H. T.; Tanner, D. E.; Hatch, D. M. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006, 39, 607–614. (Also available via the Internet at: http://iso.byu.edu/iso/isotropy.php, ISOTROPY Software Suite.)

(12) Aroyo, M.; Perez-Mato, J.; Orobengoa, D.; Tasci, E.; de la Flor, G.; Kirov, A. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2011, 43, 183–197. (Also available via the Internet at: http://www.cryst.ehu.es, Bilbao Crystallographic Server.)

(13) Conder, K.; Pomjakushina, E.; Soldatov, A.; Mitberg, E. Mater. Res. Bull. 2005, 40, 257–263.

(14) Reimers, J.; Greedan, J.; Kremer, R.; Gmelin, E.; Subramanian, M. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1991, 43, 3387–3394.

(15) Greedan, J.; Raju, N.; Maignan, A.; Simon, C.; Pedersen, J.; Niraimathi, A.; Gmelin, E.; Subramanian, M. Phys. Rev. B: Conends. Matter Mater. Phys. 1996, 54, 7189–7200.

(16) Subramanian, M.; Greedan, J.; Raju, N.; Ramirez, A.; Sleight, A. J. Phys. IV 1997, 7, C1-625–C1-628. (Also presented at the Seventh International Conference on Ferrites (ICF 7), Bordeaux, France, Sept. 3–6, 1996.)

(17) Zinkin, M. P.; Harris, M. J.; Tun, Z.; Cowley, R. A.; Wanklyn, B. M. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1996, 8, 193–197.

(18) Skaugen, A.; Schierle, E.; van der Laan, G.; Shukla, D. K.; Walker, H. C.; Weschke, E.; Strempfer, J. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2015, 91, 180409-1–180409-5.